Lovett Lake, Beechville, Nova Scotia. Courtesy of the artist.

Sylvia D. Hamilton

VISUALIZING HISTORY AND MEMORY IN THE AFRICAN NOVA SCOTIAN COMMUNITY

“Everyone should have the right and opportunity to see themselves reflected in the cultural expressions of the land in which they live.”

—Saint Claire Bourne.1

INTRODUCTION

Our history as African-descended people in this land did not begin with the large waves of Caribbean immigrants in the 1950s. Rather, it began in the 1600s with enslavement, followed by waves of free African people who came to the Atlantic Region of the land we now call Canada, following the American War of Independence in 1783 and the Canada-American War of 1812. From these earliest moments to the present day, we have used oratory, including testimony, song, speeches and prayers, and a rich variety of written texts as fundamental modes of self-expression: to write ourselves into this place. In my work as a filmmaker, writer and media artist, my practice involves finding varied ways to visualize this rich history, presence and culture through the use of still and moving images blended with music and soundscapes that give primacy to the human voice.

MINING THE ARCHIVES: PRIVATE AND PUBLIC

How does one begin the process of visualizing a buried and ignored history? In my process I create a multi-layered research map with categories such as documentary, oral, material or geographical. My first steps on this journey take me to the archives: to excavate the private sphere of family photographs and the public sphere of state archives and historical societies. Both remain essential in my work. After 40 plus years, happily, I still find images that are new to me. This underscores the on-going, pressing need for continouous research and preservation.

As we advance into the twenty-first century, our ancestral stories move further away from us, eclisped by the seemingly endless fascination with the ‘now’ as all that matters. As if the ‘now’ exists on its own, without a relationship with ‘then’. Yet I know now only exists because of then and because of them.

SCRIPT NO SCRIPT

won’t you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay.

—Lucille Clifton, “Won’t You Celebrate With Me”2

Fade up on

c. 1957. Interior. Night. One-room wooden schoolhouse. Basin shaped white lights suspended on chains from the ceiling. A young coloured girl, hair neatly parted in the centre, four braids, two sets on each side, clean, crisp blue madras patterned printed cotton dress, fitted bodice, flared skirt. Flickering light, black and white images dance on a white sheet hung from the ceiling. The room is silent. The girl’s eyes are fixed on the images.

Fast—Forward

c. Now. A filmmaker/writer/artist, the African Canadian woman stands at the back of a theatre watching an audience watch her work. During the Q & A, she says:

“I knew I always wanted to be a …”

Cut, Rewind, Rewind

No. That’s fiction, not my documentary history. I did love watching those old movies, but I had no idea when I was young that storytellling using film would occupy my future. I didn’t know that people who looked like me could make movies.

Dissolve to

BEGINNINGS

I grew up in Beechville, a Black village near Halifax that was settled by Black Refugees from the Canada – America War of 1812. As a child in the 1950s, I remember watching movies at our all Black segregated community school. Friday and Saturday nights were movie nights. They were mostly old westerns, and sometimes, other movies, likely from The National Film Board of Canada (NFB). My uncle was behind the projector, other times, a man arrived, reels in hand. Everybody crowded in, young and old alike. Without a doubt those westerns pictured characters who embodied all of the racist stereotypes that depicted Indigenous people as less than human: iconography that persists today.

Women’s Day Service, Beechville Baptist Church, Beechville, Nova Scotia, 2013.

Enter television: the black and white screen mounted in a wooden cabinet with rabbit ear antenna. Our family couldn’t afford one at first, so we trekked along the road to my aunt’s house to watch The Ed Sullivan Show, Bonanza, Hockey Night in Canada, Don Messer and His Islanders, and CBC Television’s Sing Along Jubilee, recorded in the Halifax CBC studio. There was a Black person on Sing Along Jubilee. He was simply, but fully there, part of the group, singing along … astonishing. Why—because we didn’t see Black people on TV in those days in Canada. Years later I found out the singer was Lorne White, a school teacher and principal, the youngest son of Rev. William Andrew and Izzie Dora White, and brother to Canadian singing sensation, contralto Portia White.

I had no crystal ball to show me my future—that I would eventually interview Lorne for a documentary film I was making about his famous sister Portia.3

As the CBC network developed, they created kids’ shows too: Maggie Muggins and The Friendly Giant; Frank’s Bandstand, a rock and roll dance television show for teens—some us even tried out to be dancers on the show to demonstrate we had moves too.

A Hollywood movie presented my first image of a Black person writ large on a theatre screen: Muscle Beach Party released in 1964. If I try very hard I might remember what the movie was about. What it was about though, was unimportant. The film’s only importance to me lay in the appearance of “Little Stevie Wonder” in his film debut. And what a wonder he was, projected larger than life, singing, finger snapping and playing his harmonica like there was no tomorrow. I don’t know how many times I went to see that movie, or its follow-up, Bikini Beach (1964), just to see Little Stevie. I lost count. Then came In The Heat of The Night (1967), To Sir With Love (1967) and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) with Sidney Poitier, the Man Himself. Cicely Tyson’s brilliant performances in Sounder (1972), The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1974) and Roots. It was so rare to see anyone who looked like me in movies and on TV that when it happened, it became an event, akin to a very good meal that would keep me going for a while. Solid nourishment. Comfort food.4

By the mid 1960s a regular line up of performers took over Ed Sullivan’s stage: Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, The Supremes, Gladys Knight, Marvin Gaye, and the many other Motown artists. Music was ever present in my world. My older siblings’ 45 RPMs, I claimed as mine—their voices nestled in my body, harbingers to my emphasis on the human voice and music in the work I would later create.

At night I pressed my ear to a small transistor radio, positioned the antenna, and if the weather was good, tune in WINS in New York, or a station in Presque Isle Maine to hear those soulful rhythms. It didn’t matter that I was in a small rural Black Nova Scotian village instead of Detroit, or Atlanta. What I heard connected deeply within my Black body washing over it like a sudden wave. I began making films about our experiences as African-Canadians because these films were not being made at all, or rarely in a manner that satisfied me. Above all, I needed these images. I needed to see work that came from ‘inside’ the experience. When I watched Little Stevie and Sidney Poitier, I had no idea that Black people actually made films. To see people that looked like me on the screen was a revelation; to think that they might also be behind the camera making films was beyond my frame.

Of course, if I didn’t learn about the history, culture and contributions of African Canadians, or other African descended people in my school books, why would I have been taught about their involvement in filmmaking? I was starved for images. I knew that if I was not seeing ‘me’, or people who looked like ‘me’, neither was anyone else, regardless of their background. They may not have been starving as I was, but who ever turned down a good meal. I didn’t know about the first generation of independent Black filmmakers in the United States such as Bill Foster, founder of Foster Photoplay Company in Chicago, Emmett J. Scott who produced Birth of a Race (1918), a counterpoint to D. W. Griffith’s racist Birth of a Nation (1915), or Oscar Micheaux, the most prolific of this early group.5

Filmmaker and archivist Pearl Bowser has devoted much of her career to uncovering the lost history of these filmmakers, and particularly the many women such as Haryette Miller Barton, who were a key part of this early industry. Miller Barton was a casting agent, production manager, screenwriter and director, but because of her gender, could not be credited on the films she was involved in producing.6

I didn’t know about Canada’s premiere jazz performer Eleanor Collins of Vancouver. A Canadian trailblazer, Collins began her radio career in 1938 on CBC Radio where she performed with a group called the Swing Low Quartette and later with the Ray Norris Jazz Quintet. She moved to television in 1955 and became the first variety show performer and the first Black artist in North America to host her own national television program that bore her name: The Eleanor Collins Show. ‘Canada’s First Lady of Jazz’, who, at the age of 98, lives independently in her Vancouver home, was awarded the Order of Canada in 2014. She is one of fifty members of the Order of Canada profiled in They Desire a Better Country by Lawrence Scanlan, published in 2017.7

In the 1970s when I co-developed a Black television program for a newly established cable station in Halifax, I didn’t have Ms. Collins or her groundbreaking program as reference points; no one had written that history.

Nor did I have The Black Photographers Annuals.

A knowing Black face stares directly at me from the pages of Ebony magazine. He wears a well worn leather hat, with visible stitching at the top. My dad and my uncle always wore felt dress hats. A somewhat shaggy, but not long, salt and pepper mustache and beard. I carefully removed the page to frame. I had never seen a photograph quite like it. Sometime later, my dive into Black images widened when I purchased three volumes of The Black Photographers Annual. A new world opened. Inside Volume 2, 1974, there he was in a portfolio of a photographs taken by Black photographer P.H Polk.

I absorbed the images from the Annuals into my consciousness; many years later as I began my own work, I found strikingly similar images in archives and private collections.8

CREATING THE WORK: THE WORK DOES ITS OWN WORK

Much of my work employs moving images and sound combined with text to tell stories rarely told in an effort to address these crater-like gaps in our collective history. In my films and writing, I draw from exceptional oral narratives, archival documents, material objects, music, and geography. These rich, nuanced texts inform and may sometimes contradict each other—a demonstration of our complexity and humanity. I capture and create images that have historical meaning, from my point of view, as one way of wrestling with and living with ‘history’ and as a buttress against ignorance.9

I’ve watched archeologists at Acadian and Black Loyalist sites as they went about their work, gently brushing earth and dust from small yet to be defined objects. They cordoned off the concentrated work area by placing and spacing small markers. I thought about how this process paralleled my own work framed by my interest in history and memory, both individual and collective, from the distant and near past. It is a flow backward and forward. I am interested in how the Canadian historical narrative has been constructed: how and why whole communities of people have been air-brushed out of existence. Or, if they happen to make the ‘cut’, they stand as stereotypes, victims, or exceptions to the rule, credits to their race—damned with faint praise. There is little room in this intentional construction for the detail, the complexity, the dignity and everydayness of Black, or other lives whose stories do not match, or serve the overarching white narrative.

In my work about African Canadians and African Canadian women in particular, I work against “problematizing” the people I work with so they aren’t stripped of their humanity, or reduced to sociological constructs. I strive to see and present people as ‘whole’, complex beings—to find beauty in them as an antidote to the ugliness of the experiences that accompany the endless negotiation of daily survival. People appearing in my films, with few exceptions, have had little if any experience with media. Previous encounters, more often than not, were negative.

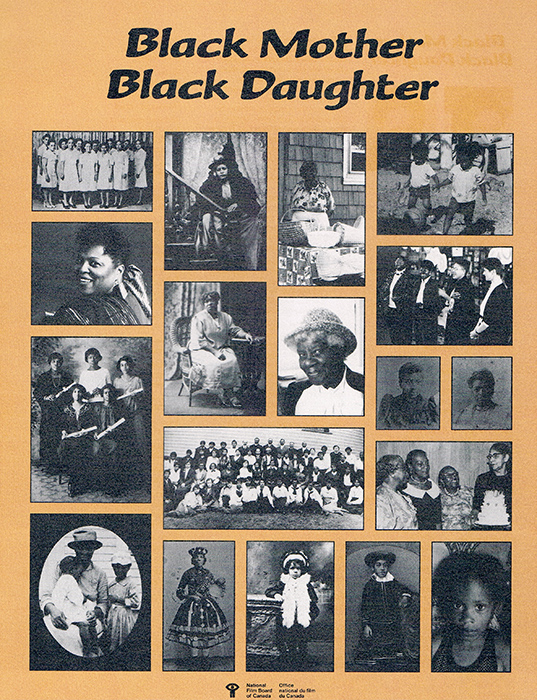

Black Mother Black Daughter (1989). Production still, Women’s Day Service, North Preston, Nova Scotia. Left to Right: Co-director Sylvia D. Hamilton, Elders, Dr. Ruth Johnson and Dr. Marie Hamilton, the filmmaker’s mother.

Finding the financial resources to make the films was a tough challenge, convincing people to give up their privacy, to trust me, and to talk about matters never spoken about in public, let alone on film, was another. This work comes with enormous moral and ethical responsibilities. In the larger context, I struggle against the superficial knowledge many Canadians have about African descended people in Nova Scotia and Canada; they have segmented, strands received via the media: ‘Race riot in a Nova Scotian school’, ‘Racial flare- ups at Halifax bars’. These flash points supposedly about us, come and go as they cement the stereotypes or are treated as ‘isolated incidents’. Otherwise, we have little presence, other than as spectres, in the Canadian imaginary, despite centuries of deep roots.

Like my ancestors before me, I navigate my way through these rough waters. Memory is not linear; it is a push-pull process operating on simultaneous planes, one of which is informed by the photographic image. Treasured family photographs are a visual map, an archive of the interior lives of African Nova Scotians. They chart experiences, moments of presence that are invisible to a broader society, that in spite of its best efforts, was not able to erase them. Ignore them yes, but never erase or eliminate them because of the visual evidence of family archives, and family bibles charting the genealogy.

While not recorded, or when written about pejoratively in historical records or popular publications, individuals and communities existed in defiance.

When researchers from the outside of the community took photographs, later depositing them in public archives, unbeknownst to them, the people photographed had images they took of themselves. My use of such external images is a re-purposed one; I place them in a different frame, figuratively and actually. What I see is much like my re-interpretation of the freedom runner (a term I coined because of my different reading) advertisements found in archival newspapers.

My reading uncovers agency, determination and cleverness. In these re-purposed photographs, I read a sense of style, of knowing, perhaps with a quiet awareness, that in a future time, someone like me, one of them, would arrive to rescue them, to re-present them within their Black community context.

One of the most radical things that can happen in film is the foregrounding of black subjectivity. Because, essentially black people always end up being the backdrop, but very seldom are we in the subject position.

—Arthur Jafa10

In my documentary Black Mother Black Daughter (1989), Cleo Whiley sits at her dining room table, showing her friend Lavina Harris her treasured family photo album; I also use images from public archives and historical societies. In Walk Through Time, one of the Nova Scotia Vignettes Series, I created a visual montage of still images and archival footage underscored by the voice of African Baptist minister and educator Dr. W.P.Oliver. He says, “Even just to look at their faces, expressions, tells me something of their life experiences.”11 I was reminded of James Baldwin’s introduction to Volume 3 of The Black Photographers Annual; commenting on images created by photographer Anthony Barboza, Baldwin writes: “ They would appear to know, and from experience, how little to expect from the people among whom they find themselves, and how much they must, therefore expect from each other.”12 Documentary filmmaking is a process: the filmmaker captures a set of moments in time. I enter the conversation, then leave, hinting that the conversation continues long after my exit.

My work speaks to the dichotomy of absence and presence. I populate and visualize Black/African descended people in multiple spaces, locations, and geographies. We were ‘absent’ but I show that we are vitally, fully present.

INTEROGATING THE ICONOGRAPHY

Citadel Hill in Halifax is a quintessential Canadian historical site and tourist magnet. I used to live just below the Citadel on Brunswick Street. The windows of my third floor apartment faced the Hill and the Town Clock. At noon each day my building shook as the cannon blast marked the time. At night, with lights out, I stared out of my window thinking of the Trelawney Maroons: bold Africans in Jamaica who fought and defied the British to maintain their freedom. After signing a peace treaty, the British Crown broke its promise exiling them to Nova Scotia in 1796. They helped build the 3rd fortification at the Citadel. I shot a segment of the Hymn To Freedom television series titled, Against the Tides: The Jones Family there, placing my host, broadcaster and legendary producer Fil Fraser, amongst a group of tourists. The sequence tells the story of Maroon involvement in the construction of the fortifications. After screenings of this film, Canadian audiences are surprised: this was not the representation of the Citadel they’ve grown up with. They knew nothing of the role the Maroons played in this landmark.

Poster for Black Mother Black Daughter (1989).

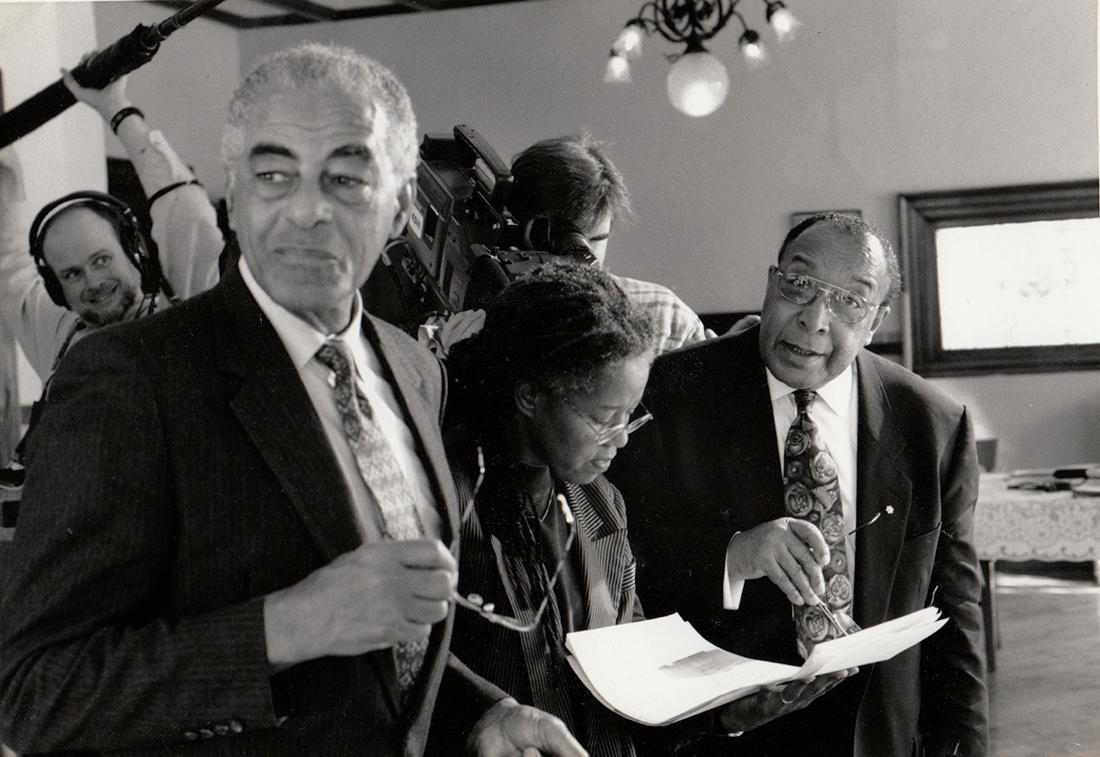

Working with Fil Fraser, the ever consummate professional, was a daunting privilege. I first met him in Montreal in the late 1970s at a Black Artists’ Conference organized by writer and editor Lorris Elliot. Fil was the first Black producer/filmmaker I had ever met. In 1977 he had just produced Why Shoot the Teacher, at the time, Canada’s most successful feature film. Now on set in 1993 as a newish director, I was directing him as the host of the Jones Family episode.

Speak it! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia (1992). Production still, St. Patrick’s High School, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Immediately, he put me at ease: whatever I wanted him to do, he was ready. “You’re the director” he said, “direct me”.

I wrote and re-wrote his narrative segments on the fly, on poster board. We had no teleprompter. Patient and kind, he nailed the text every time, usually in one take. Fil was an industry veteran, a founder of film and media organizations, a human rights leader and the first CEO of Vision TV (1989–1992), where our paths crossed again when I started work on my Portia White film.

When Fil Fraser died in April 2017, at the age of 86, after a long eminent career, he left an indelible mark on the film and television industries. He made the path a lot easier for many of us: he demonstrated what was possible to do in Canada.13

In another film, Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia (1992), about Black youth, identity, race and empowerment, I created a number of sequences that challenge the dominant iconic images of Nova Scotia. These young African Nova Scotian students were searching for themselves in their school environment. I positioned my narrator, Shingai Nyajeka, a young dreadlocked African Nova Scotian male, in a shot with the Halifax Town Clock as his backdrop. It’s not the typical picture postcard image found in tourist shops, or the classic representation of one of Nova Scotia’s landmark locations widely promoted in tourism advertisements. In another scene, Shingai sits at the edge of a wharf at the Halifax waterfront with Nova Scotia’s legendary sailing ship, the Bluenose, in full sail, captured behind him.

Later we see him in a frame set against the George’s Island lighthouse located in Halifax harbour; he walks in front of a Scottish bagpiper at the entrance of the Halifax Public Gardens, a popular, traditional Victorian style garden. With these juxtapositions I locate us, people of African descent, in the Nova Scotian and Canadian landscapes. My work becomes one of the ways I talk back to previous work and interpretations that have erased our full history, lives and experiences from constructions of Canada. I render visible what’s been missing from mainstream representations of Nova Scotia and Canada. The work becomes a way for me to speak directly to African descended people in Canada and elsewhere. It is my entry point to my primary audience.14

With documentary films we establish the conditions for engagement, by making work that can be a collective viewing experience whether or not the filmmaker is present. When my films are screened in public or in classrooms across Canada, I am not privy to the subsequent conversations or questions that arise. The film is ‘out of me’ so to speak, how viewers respond, or what knowledge they bring is beyond my control. The work is in the world, doing its own work. Sometimes it sends back missives. In various locations in Nova Scotia and elsewhere in Canada, people approach me to say they saw Black Mother Black Daughter, during a class in high school or university, or they saw it on television. They remember the women, they were touched by their stories.15

No More Secrets (1999), a two part documentary about violence against women in the Black community, was an effort to crack open a topic that we have been reluctant to talk about or address publicly. The very lives of women and children are continually at stake because of the deafening silence; we turn away when we are not sure what we can do.

It was and remains a very brave act on the part of the women who revealed their personal stories in this documentary; they did so with the profound hope that they might help combat this serious problem. This forthright action was a courageous step for the Women’s Institute, the umbrella organization of women’s societies within the African United Baptist Association of Nova Scotia that commissioned the work.16

VISUAL AESTHETICS

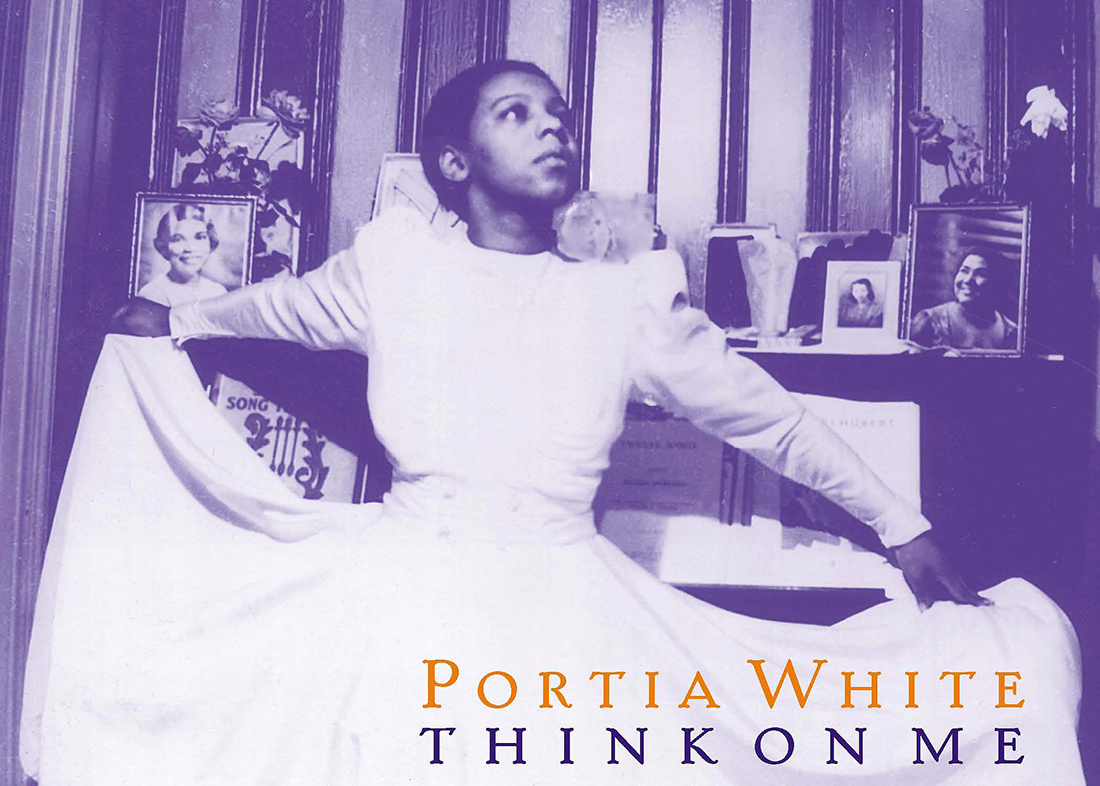

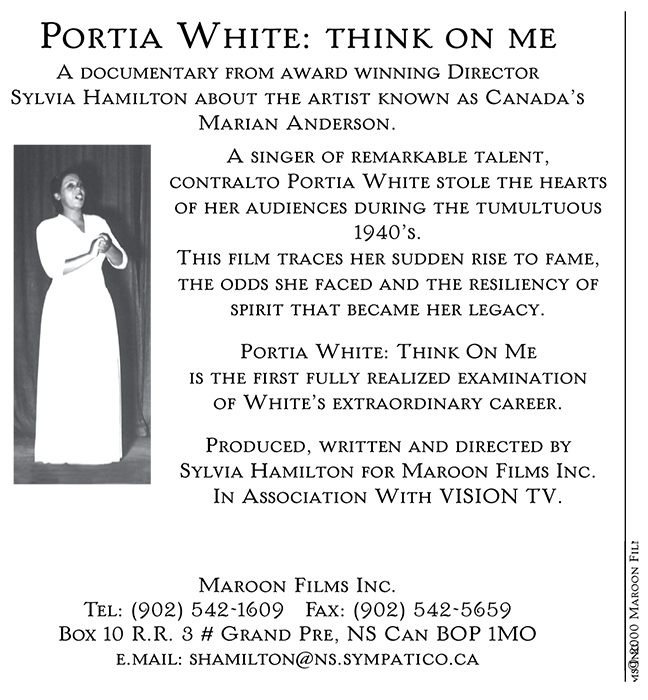

Two films, Portia White: Think On Me (2000) and The Little Black School House (2007) are prime examples of the integral role archival still and moving images, along with sound, play in my visual aesthetic.

Portia White: Think on Me took years to make; during the process I was on a rescue mission—an effort to salvage her memory, presence, image and voice. Portia Mae White died in 1968, film or television footage of her was rare. I relied heavily on the still image to visualize her story. She was a singular, independent woman of Africent descent from Nova Scotia who dared to become an artist in the 1940’s. How audacious. Portia’s race was singled out for mention in the vast majority of her press coverage and she received a lot of ink. Canada’s star performer was praised in prominent Canadian and American newspapers and magazines; she was labelled ‘Canada’s Marian Anderson’, the ‘Daughter of Destiny’ and ‘Canada’s Singing Sensation’. At the time, she had no equal, of any background. In spite of her acclaim, she was written out of books on the musical, cultural or artistic history of Canada. Here and there I found the occasional mention, but no biography or major examination of her life and work, or her contribution to Canadian arts existed when I embarked on my documentary project in the late 1990s.

Postcard for Portia White: Think on Me (2000).

Decades before any of the current Canadian divas and singers were even born, White was touring extensively as a solo artist throughout Canada, the United States, the Caribbean and South America, astounding critics and audiences alike with her remarkable voice, stage presence and intelligence.

I wanted people to know something of the achievements and struggles of Canada’s first diva: she was more than a name. Decades had passed since Portia White’s many concerts in the 1940s. With the passage of time, tracings become faint, making the research complex, daunting and often, overwhelmingly discouraging. My research map was in constant flux, as routes and byways were created, abandoned and reestablished when new scraps of information came into view.

I created a birth to death chronology, with the dates of the various known events in her life and amassed a room full of research:

multiple to do and to find lists; coloured coded file cards of notes; stacks of notebooks; computer discs; banker boxes of material including newspaper clippings, photographs, letters, sheet music and concert programs; books on music; biographies of women; early recordings of her contemporaries: Marian Anderson, Dorothy Maynor, Renata Tebaldi, Ghena Dimitrova, Roland Hayes and Paul Robeson.

My interviews began with Portia’s family in Halifax, Toronto and Montreal and I was guided by their stories, suggestions, and memorabilia. Their cooperation was generous, always supportive and most encouraging. Later I added the names of Portia’s friends, professional associates and colleagues to my ‘to find list’. Anyone I succeeded in finding gave further leads, more fragments, more clues. In the process, I found individuals who had seen her perform, or who had been her voice students. I followed slim leads, many of which were dead ends, others pointed to someone, or something else. I sought out experts in the field who could provide context and a deeper understanding of the life and career of a concert performer at that time.

Historian Hilary Russell, who had completed research on Portia White for the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, which subsequently designated Portia as a person of national significance, was an invaluable colleague who generously shared her research, and serendipitously, her family. While researching, she discovered that her mother, Jean McFarlane had seen Portia perform in Kingston, Jamaica during Portia’s three-month tour of Central and South America and the Caribbean in 1946. I took advantage of any public opportunities to promote the research and placed an ad in the Globe and Mail’s personals column with the hope of turning up people or material.

Elated, I received responses that led directly to two significant interviews. I searched public and private archives, libraries and historical societies in Canada and the United States. Any details that emerged, or were gleaned from conversations became plot points on the reseach map or in the chronology. I shadowed Portia. I walked where she walked in Halifax, to Cornwallis Street Baptist Church. I rode the train to Moncton, New Brunswick and walked the streets of the Toronto neighbourhood where she lived and taught in her studio.

I stood in the expansive baseball field at Detroit’s Briggs, (formerly Tiger) Stadium where she performed, spent nights at Winnipeg’s Fort Garry Hotel where she met her faithful

accompanist, and later my very generous interview subject, Gordon Kushner, and sat in the balcony of Ottawa’s First Baptist Church, the venue for her last public performance. During the research process I spoke with more than fifty people about Portia White, her life and career. From this initial grouping, I selected twenty-two people for on-camera interviews, which were filmed in and around Halifax, Nova Scotia, Toronto, Ottawa and Detroit.

I filmed archival material at the Nova Scotia Archives, the Ontario Black History Society in Toronto, York University Archives, Toronto Reference Library, National Archives and Library in Ottawa and the Detroit Public Library. I collected additional archival material and still photographs from personal collections in Halifax and Toronto. I purchased precious seconds of rare archival footage and sound recordings from the National Film Board of Canada and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Archives.

During editing we poured over every single still image and the archival footage of Portia to create a visual approach that would evoke and centre her presence throughout, with her speaking and singing voice as the spine of the film. Another fundamental structural element was my presence as the on-camera guide. I had embarked on this story-journey, after so many years I was completely inside it; my editor asked rather rhetorically, who else could narrate this film.

Interviewing people who after fifty years, treasured crisp memories of Portia White told me she was no ordinary person—her lasting imprint on the people who saw her, who worked with her, or were her family was palpable.17

TELLING THE TRUTH

Segregated schools are a barrier to good inter-group relations. They are a visible symbol of separation, and a denial of the right ‘to belong.’ Such schools became the stamp of approval of the mental apartheid that exists in many white minds.

—Dr. William P. Oliver18

My work is preoccupied with at least two fundamental questions: whose memories have we failed to represent, and what memories do we not want to represent and why? The enslavement of African-descended people and its pernicious legacy in Canada sits at the cusp of these troubling questions. Whether we wish to remember, or not, the educational segregation of children of African descent in Canada and elsewhere is a direct by-product of the system of chattel slavery, an institution whose goal was to strip African people of their dignity and humanity in order to use them as property, vehicles of cheap labour for a profit-making capitalist system.

The Little Black School House (2007) is my one-hour documentary film that tells the story of segregated schools in Canada, the teachers who taught there and the students they taught. It is also the story of the struggle of African Canadians to achieve dignity and equality through the pursuit of education. Segregation in education is associated with the United States and South Africa. In 1954, while the US Supreme Court was moving to prohibit racial segregation in schools by its landmark ruling in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, schools segregated by race were in full operation in communities in Nova Scotia and Ontario. Structurally, the film is a multi-voiced inter-generational narrative.

Reunion of Retired Teachers of Segregated Schools in Nova Scotia at The Black Cultural Centre of Nova Scotia, Dartmouth, September 1990.

I interview people who either taught in, had been students, or were the parents of children who attended segregated schools, and knowledgeable historians and educators who situate these schools within the broader socio-political context. Sequences with elementary school students, and a multi-racial group of high school students bring the story to into the present.19

All willingly engaged in this public act of remembering, one where the individual stories taken together shape a collective memory that holds a complicated truth about segrega- tion and what that meant: forced exclusion on the basis of race, lack of basic physical and educational resources, and limitations on access to further education that extinguished the dreams of so many students and their parents.

Yet, for the most part, Black teachers who were fiercely devoted, taught their students well, held them to the highest standards, inculcated a strong work ethic, and did all that they could to equip them to live in a society that might reject them because of their race. They displayed creativity, innovation, and resilience. This film is a sibling to my short film titled Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia, discussed earlier, about Black youth, race, identity, and empowerment. In one crucial scene, Shingai delivers a speech to his class titled, “Canada at 125: One Hundred and Twenty-Five years of Black History in Nova Scotia”. Over a visual montage of images of Black Nova Scotians, underscored by a soundscape of voices, he says: “We can’t forget that Nova Scotia was a slave society.” In another scene, during a dramatic monologue, Shawn, Shingai’s classmate, reminds the viewer about segregated schools.

The Little Black School House (2007). Production still, Guysborough County, Nova Scotia. Left to Right, Reed Jones, Production Intern, Director Sylvia D. Hamilton, Sound Recordist Dan Stewart and Cinematographer Kent Nason.

The Little Black School House (2007). Production still, Guysborough County, Nova Scotia. Left to Right, Reed Jones, Production Intern, Director Sylvia D. Hamilton, Sound Recordist Dan Stewart and Cinematographer Kent Nason.

In The Little Black School House we see elders with high school students, first inside the school and later on a school bus, telling them stories of what it was like attending segregated schools. The school bus carried this unusual group of passengers to these ‘sites of memory’ in Guysborough County—the location of former segregated schools.

Those moments, and the 184th anniversary service of Tracadie United Baptist Church, are memories visualized on film that stand as markers against forgetting. This film gives visual evidence of segregation in education by presenting the story through on-camera interviews with the people most affected; individual and class photographs; contemporary on location visuals and rare archival footage of the interior of a class. This is the visual landscape of the documentary. A Black teacher instructs her all Black class. She asks questions, students stand to respond: “Can anyone tell me what Britain gained by the Treaty of Utrecht? By the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 Britain was given Newfoundland and all of Nova Scotia”. I saw echoes of my own segregated school experience. The young girl standing beside her desk to answer her teacher could easily have been me, members of my family, or my many cousins and neighbours.

I chose not to use archival footage or still images from schools in the US or South Africa in The Little Black School House to ensure that the story would be clearly seen and defined as a Canadian story, a made-in-Canada experience, one hardly admitted to and never before told in film.

The sense of place, the geography, is of the utmost consequence precisely because it is a Canadian story and must be understood as such. The question then is this: how can a memory be vivid, emotional, so present, as if yesterday, in one sector of Canadian society, yet more broadly, in another, no apparent memory? I say apparent since it is hard to understand such lapses in the memory of those who—given their proximity, geography, and time period—should have known.

In The Little Black School House, Production Still. Elders and students inside the Afrikan Canadian Heritage and Friendship Centre, Chedabucto Education Centre/Guysborough, Guysborough County, Nova Scotia, 2007.

In my films we see the witnesses on screen: their faces, their bodies, their voices— visualizing their story counters ignorance and denial. What the people who appear remember, they remember for all of us in this land.

EXCAVATION

To further explore ways of visualizing our stories, I embarked on what became a five year multi-media art installation titled Excavation, that explores the interlaced themes of history, personal and collective, and memory in the lives, connections and experiences of African Canadians across time and space.

Since its first iteration, Excavation: A Site of Memory, at the Dalhousie University Art Gallery in the fall of 2013, five other galleries and museums have exhibited the work. Its centrepiece is five fourteen-foot-long wall scrolls, containing more than three thousand names of African people digitally printed on fabric, the scrolls suspended from above, with accompanying voice soundscape. The overal installation features video projections, large text prints and objects and materials from my personal archive. At each specific site, I mine materials and objects from that location to incorporate within the installation. In a 2018 iteration of the installation at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), titled Here We Are Here, I integrated archival prints from the 1700’s, the same time period of the Transatlantic slave trade, and racist golliwog dolls from the late 19th century. The prints and objects came from the ROM’s collections. This project concretizes and visualizes the memories and experiences of African-descended people in Canada. Implicitly it asks questions about absence and presence.20

Excavation: A Site of Memory. Multi-media installation, Dalhousie Art Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia, 2013.

Historian Pierre Nora, writes about creating ‘lieux de memoir, or sites of memory. Nora says the most fundamental purpose of ‘lieu de memoir’ is to stop time, to block the work of forgetting.21 I want my work to bear witness: to be visual sites of memory so that we never forget.

All images Courtesy of Sylvia D. Hamilton

NOTES

1 Saint Claire Bourne, “Bright Moments,” Z Magazine (1989): 40-41.

2 Lucille Clifton, “won’t you celebrate with me,” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50974/wont-you-celebrate-with-me. (accessed 2 May 2018).

3 Sylvia D. Hamilton, Portia White: Think On Me. 16 mm. Directed and Produced by Sylvia D. Hamilton. Maroon Films Inc. 2000.

4 Asher, William. Muscle Beach Party. Directed by William Asher. Los Angeles: American International Pictures,1964; Asher. Bikini Beach. Los Angeles: American International Pictures,1964; Jewison, Norman. In the Heat of the Night. Directed by Norman Jewison. Beverly Hills: United Artists,1967; Clavell, James.

To Sir With Love. Directed by James Clavell. Culver City: Columbia Pictures, 1967; Kramer, Stanley. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Directed by Stanley Kramer. Culver City: Columbia Pictures, 1967; Ritt, Martin. Sounder. Directed by Martin Ritt. Los Angeles: 20th Century Fox,1972; Korty, John. The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. Directed by John Korty. New York: CBS, 1974; Chomsky, Marvin J, Eman, John, Greene, David, Moses, Gilbert. Directors. Roots. Burbank: Warner Brothers Television, 1977.

5 See James Snead’s chapter, ‘Birth of a Nation,” in White Screens Black Images: Hollywood From the Dark Side, James Snead, eds. Colin MacCabe and Cornel West, (New York and London, Routledge, 1994),37-45. For a discussion of the evolution of Black/African-American film and filmmakers, see Manthia Diawara, Black American Cinema (New York: American Film Institute, 1993; Nelson George, Black Face: Reflections on African-Americans and the Movies (New York: HarperCollins, 1994); Ed Guerrero, Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993); and bell hooks, Reel to Real: Race, class and sex in the movies (New York and London: Routledge, 1996)

6 Alexandra Juhasz, Women of Vision: Histories in feminist film and video. (University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2001), 52.

7 Judith Maxie, Personal email message to author, February 21, 2018. Judith is an actor and the daughter of Eleanor Collins (b. November 21, 1919). See. https://bcblackhistory.ca/eleanor-collins/; “ CANADA 150: New book about Order of Canada winners sings praises of Surrey’s ‘First Lady of Jazz,’ Eleanor Collins, 98,” https://www.surreynowleader.com/community/canada-150-new-book-about-order-of-canada-winners-sings-praises-of-surreys-first-lady-of-jazz-eleanor-collins-98/

8 Joe Crawford, The Black Photographers Annual 1973, With a Foreward by Toni Morrison and An Introduction by Clayton Riley (Brooklyn: Rapoport Printing Corp. 1972). I have Volume 2, (1974) and Volume 3 (1976) which includes a Foreward by Gordon Parks and An Introduction by James Baldwin.

9 See Sylvia D Hamilton, “A Daughter’s Journey,” Women and the Black Diaspora, Canadian Woman Studies 23, 2 (Winter 2004): 6-12.

10 bell hooks, Reel to Real (New York: Routledge Classics, 2009), 222-223.

11 Sylvia D. Hamilton, Nova Scotia Vignettes, Directed and Produced by Sylvia D. Hamilton, Halifax: CBC Television and Maroon Films Inc., 1996. This was a ten part series of minute television vignettes.

12 Crawford, Black Photographers Annual Volume 3, 1976. James Baldwin was living in St. Paul de Vence, France in 1976 when he wrote the introduction that also included this passage: “This book is a testimony— I am tempted to call it a testimony service—and, like all truthful witnessing, it is beautiful and frightening, devastating and ennobling.” These Annuals were that and much more to me.

13 Sylvia D. Hamilton, Against the Tides: The Jones Family. Directed and co-written by Sylvia D. Hamilton. Toronto: Almeta Speaks Productions, 1994. This documentary was part of a four hour mini-television series titled Hymn to Freedom, about the history and contributions of African Canadians produced by Almeta Speaks, for Almeta Speaks Productions. Fil Fraser, who hosted the series, went on to write Running Uphill: The Fast, Short Life of Canadian Champion Harry Jerome, which was published in 2006 by Dragon Hill Publishing Ltd., Edmonton, Alberta. Filmed on location in Truro, Pictou and Halifax, Against the Tides features members of the family of Wilena and the Elmer Jones, of Truro. Wilena, Burnley (Rocky), Janis, Lynn and granddaughter Tracey show a family legacy of caring for both family, and the extended family of the Black Community. Through their good humoured stories and reflections a picture emerges of a dedicated family of activists, who believe in the importance of social change and their role and responsibility to make change.

14 Sylvia D. Hamilton, Speak It! From the Heart of Black Nova Scotia. Directed and co-written by Sylvia D. Hamilton. Montreal: National Film Board of Canada,1992. It won a Gemini Award, the 21st Maeda Japan Prize, and the Best Canadian Documentary Award at the Atlantic Film Festival. Speak It! screened internationally at the Margaret Mead Film Festival in New York, Femi International Festival in Guadeloupe, the 6th International Film Festival in Creteil, Paris and the Melbourne International Film Festival. Canadian broadcasts included CBC, Vision, and TVO. In 2017 it was screened in the Redux Program at the Hot Docs Film Festival in Toronto.

15 This modest first film has enjoyed a remarkable long life since its launch in 1989. It screened as part of the BFI (British Film Institute) Black Star Retrospective of One Hundred Years of Black film hosted by the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) in November 2017. Decades earlier it premiered in the Canadian Perspectives Program at the 14th Festival of Festivals, the original name for TIFF. In April 2018, Hot Docs Canadian International Film Festival screened it as part of its Redux series.

16 The African United Baptist Association was founded in 1854 by Rev.Richard Preston, a Black Refugee of the War of 1812. This organization followed its founder’s philosophy of attending to the members’ spiritual and social needs. Much of this work that is tied to social and community development has been taken on by women who formally organized themselves in 1917 into ladies auxiliaries.

17 Sylvia D. Hamilton, Portia White: Think on Me. Written, directed and produced by Sylvia D. Hamilton. Grand Pre, Nova Scotia: Maroon Films Inc., 2000. Within the past number of years, public interest in Portia White (1911-1968) and her legacy has continued to grow. She was designated a person of national significance by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada, Canada Post issued a postage stamp to commemorate her, and the Nova Scotia government created and named a major arts award, The Portia White Prize, in her honour.

18 Colin A Thomson, Born With A Call: A Biography of Dr. William Pearly Oliver, c.m. (Dartmouth: Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia, 1986).

19 Sylvia D. Hamilton, The Little Black School House. Researched, written, directed and produced by Sylvia D. Hamilton. Grand Pre, Nova Scotia: Maroon Films Inc., 2007. After its sold-out premiere at the Atlantic Film Festival (AFF) in September 2007, students across Nova Scotia viewed it in school screenings during a special ‘Festival in a Van’ travelling program organized by the AFF. It was broadcast on the Knowledge Network, CBC and TVO; it was subsequently screened in public venues across Canada and featured at the 2009 African Diaspora Film Festival at the Schomburg Centre for Black Culture in New York. As recently as February 2018, I was invited to show it during the 2018 Ontario Education Research Symposium held in Toronto. Following the screening, Bruce Rodrigues, Deputy Minister of Education Responsible for Early Years and Child Care, host for the evening, engaged me in conversation about the film, its themes and continuing relevance and I responded to questions from the audience. The majority of attendees had not known that segregated schools existed in Canada, and specifically in their home province of Ontario.

For a discussion of the development and production of The Little Black School House, see my chapter “Stories from The Little Black School House’, in Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation through the Lens of Cultural Diversity, edited by Ashok Mathur, Jonathan Dewar, and Mike DeGagne, Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2011. For an introduction to the landmark Brown v. Board of Education, see, Charles J Oglegtree Jr., All Deliberate Speed: Reflections on the First Half-Century of Brown v Board of Education (New York: W.W.Norton & Company, 2004)

20 In 2004 I was one of the artists selected for a thematic residency at the Banff Centre as part of the Intra-Nation Project. It was during this residency that I first articulated and tested the idea for what became Excavation: A Site of Memory. At the time I wrote: “African Canadians since our earliest days in Canada have strived to find a compass—to locate ourselves in this vast land: to plot our position on the physical and mental map of Canada. I am a direct descendant of one group of those early pioneers, the Black Refugees of the War of 1812. I have become a seeker trying to find some of the co-ordinates, not just for my self, but also for others. I am deeply conscious that I am able to be here because of those many who have gone before. My work re-inserts and re-positions African descended people in the Nova Scotian and Canadian landscapes by creating stories and presenting images of people being witnesses to their own lives. Essentialist representations of Nova Scotians evoke rural, white, male, fisherfolk, or kilt wearing, bagpipe playing Scots from the Cape Breton Highlands. These have become the iconic images of Nova Scotia leaving no room for the diversity of people who have lived here for generations. “ (Artist’s Statement, 2003-2004) Following the installation at the Dalhousie Art Gallery in 2013, other iterations were mounted at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax (2014), The Thames Art Gallery in Chatham, Ontario (2015), The Schulitch School of Law, Dalhousie University (2016), and the University of New Brunswick Art Centre in Fredericton (2018). The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) used the title of my work, Here We Are Here, that I created for the Law School iteration as title for its 2018 exhibition of contemporary Black Canadian art that later travelled to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal in May 2018 and to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in May 2019.

21 Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Memoire.” History and Memory in African- American Culture, eds, Genevieve Fabre and Robert O’Meally, Oxford University Press, 1994), 284-300.