Davide Pan, Activating the Archive (2010). Photo by Henri Robideau.

Glenn Alteen

ACTIVATING ARCHIVES

Artist-run centre (ARC) archives in Canada are a rich and underused resource of our histories. They not only tell the story of individual producers, but they also tell of communities of inquiry that have been important to wider cultural development in Canada. The importance of ARCs is sometimes lost in the list of Selected Solo Exhibitions on artists’ CVs, but their history in the development of new work cannot be understated. Also telling are the communities that are missing in these archives and the marginalized practices that were not included. It is important to recognize that artists’ centres have not served everyone and in hindsight these omissions become glaringly apparent.

Over the past 45 years, much artwork got produced in Canada simply because there were artist-run centres to show it, and the country is peppered with stories of that work moving on to public and commercial galleries later, with great success. The archives of centres are the heart of these stories, those difficult conceptions which initially didn’t always work–how artworks were forged, how they adapted, developed, and morphed into work that was possible in other institutions and celebrated across Canada and abroad. These stories need to be told and this work needs to be seen by younger producers and curators. It needs to be seen for who was included but also for who was left out. For what it contains and for what it doesn’t.

ARCs were built out of a framework of marginal practices that stood stalwartly against a commercial mainstream, where they saw themselves as an alternative. But as we move further into our digital universe, that mainstream has shattered into dozens of minor streams, none of which can be said to have clear dominance. Our role of being alternate to anything has disappeared and we are free to move within a decentred information universe. As well, the long histories of these centres do represent underlying stability going back decades. Their dedication over 40 years to specific and once marginalized practices represent a continuity that is increasingly rare and represent a certain authority.

The archives have become a major development in several centres on the West Coast. Besides grunt, Western Front and VIVO have both developed major initiatives around their archives over the past ten years and this is changing the culture of artist-run centres here. Open Space, Access, and 221A have also devoted organizational energy to their archives more recently. One result is the emergence of information specialists: archivists and librarians within the ARCs creating another layer of specialization and engagement. This has included hiring archivists through project funding and more recently through permanent hires, volunteer and intern opportunities in the centres, and collaborations with the universities beyond the usual Art History and Studio Programs to programs in Information Studies. At grunt this has developed into longer-term collaborations with the First Nations and Indigenous Studies Department at UBC, and the Making Culture Lab in the Digital Anthropology Department at SFU.

Activating The Archive (ATA) was a 2011 project consisting of six websites produced out of the archives at grunt gallery. The project revolved around putting archival work on the web in curated sites that propose activations in the form of new curation, new scholarship and writing, and in some cases new commissions based in new production. ATA attempts not to show why work was historically important as much as how older work can be relevant and inform new practice today. Curatorial teams included, in some cases, curators who had worked on the project originally who began working with younger curators and artists to find work that was relevant to them now, creating an intergenerational mix. Because our archives contain work by Indigenous, Queer and artists from marginalized communities, participants were able to interface with work that is not readily available in most archives.

This essay will look at some of the issues that arose out of producing this large project and the impacts that had within our organization and beyond.

The development and programming of our archive at grunt came out of a series of websites we began developing in 2005 that allowed curators into our archives to develop online exhibitions of current and sometimes historical material. By 2009 we were pretty adept at developing websites after researching and implementing the protocols for rendering and editing material to go on the web. In 2009 we worked with the Belkin Gallery, UBC, and curator Lorna Brown to develop Ruins in Process—Vancouver Art of the Sixties. The project engaged viewers in the work of the era with archival materials mixed with new curation, scholarship, and engagement that included many of the original artists as well as younger students and scholars.

The project worked because of these activations, using students and the original artists together with art historians to create a dynamic site. It inspired a series of exhibitions since 2009 in various Vancouver art institutions documenting 1960s production. Moreover, it made that production available to curators, scholars, and students to study and develop.

After this project, we looked at our own archives at grunt and considered ways to get a sizeable amount online. We had always taken extensive documentation of exhibitions and performances at grunt and have slides, black and white photography, and video dating back to our earliest period. It sat in file folders until 1998, when curator Brice Canyon organized the archive into binders editing the files. Throughout the 2000s, the archive was the site of much volunteer work and benefited from a couple of job grants allowing us to set up a database of exhibitions and events. As these improvements happened, there developed an interest by curators and scholars to work in our archives because of our unique holdings of artists from marginalized communities and/or working in marginalized practices. Central to this was our extensive collection of performance work by First Nations artists and others. As well our history in community practices over many years has generated wide interest.

Ruins in Process had shown us how the intergenerational transfer of information varied in these situations around archives, and how younger eyes often saw very different things than might have come to attention when the work was first exhibited. We later learned that putting work on the web exposed the work to much larger audiences than those available in their initial offering. Exhibitions and events seen by at most a couple hundred people were suddenly being seen by thousands on the web, their second life getting considerably more exposure than their first.

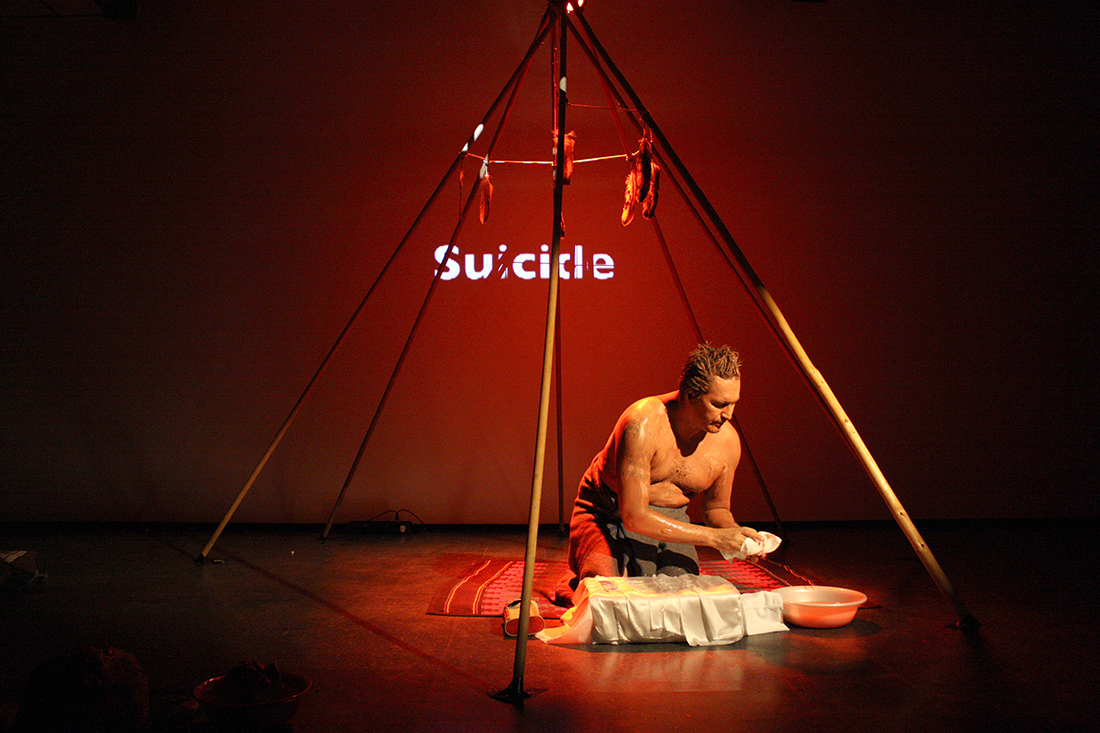

Adrian Stimson, White Shame Re-Worked (2012). Perfomance. (Original performance by Âhasiw Maskêgon-Iskwêw, 1992). Photo by Merle Addison.

Activating the Archive became our initial project into the archives at grunt. It began with an exhibition that brought our archives out from our upstairs shelves and into the gallery, allowing the public to come and research exhibitions, and we ran programs that focused on different themes or areas. The whole history of the organization was on view and people were very interested in what they could find. Starting with the physical archive, our thoughts moved later to our digital archives and the (by then) considerable number of websites grunt had been producing since 2005.

The online portion of Activating the Archives was funded through Heritage Canada Interactive Fund and the project allowed us to develop an online database as well as six curated sites. The project included over 30 participants in roles of research, digitization, web development, curation, copyright, and marketing. The project started with an invitation to explore our archives to develop web sites that reimagined the archive in new ways and extended into new directions. By encouraging new curating and writing, as well as projects and commissions, we were able to move beyond just the uploading of databases to a reinterpretation of the material.

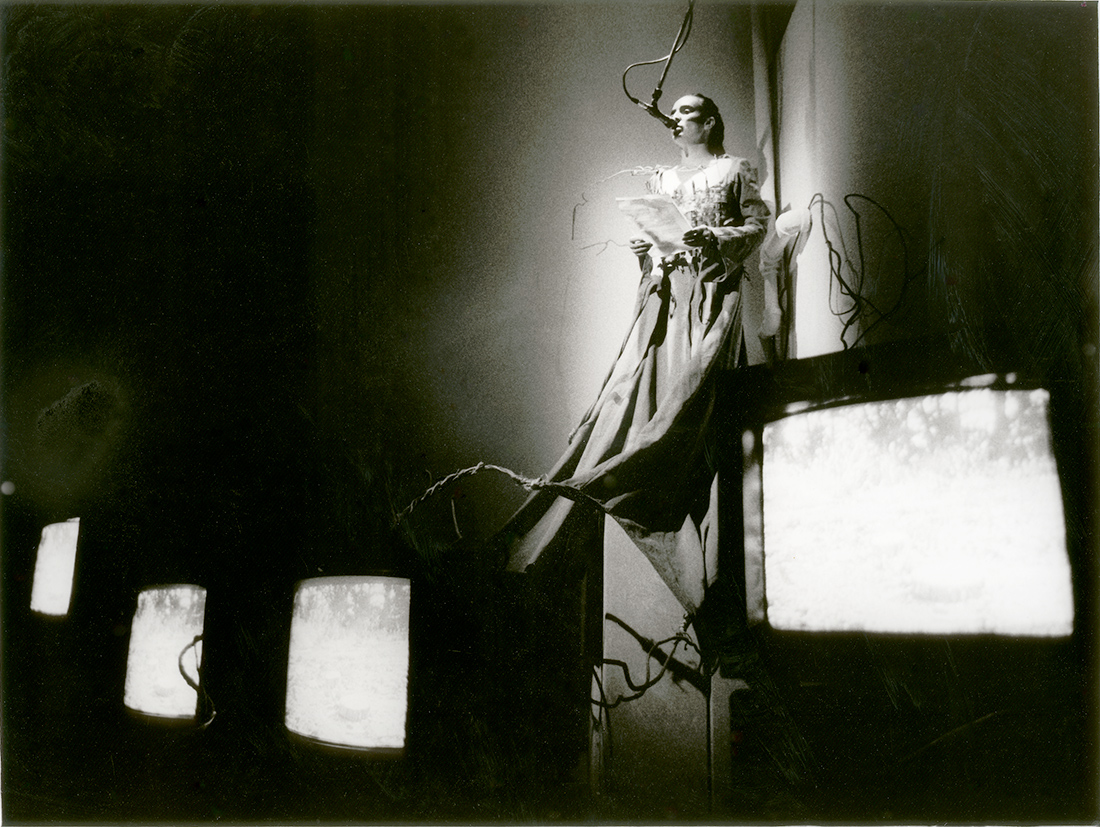

OLIV with Aiyyana Maracle, Stephen Anthony, and Haruko Okano, Facets of Human Sexuality (1995). Performance from the Transgendered Cabaret, part of the Halfbred series. Photo by Merle Addison.

For the website Ghostkeeper this included a lot of reinterpretation. One of the projects focused on the new media and performance works of Âhasiw Maskêgon-Iskwêw. New writings were commissioned from Steve Loft, Marcia Crosby, Sara Diamond, and Zainab Verjee. New performances and media works were commissioned from Cheryl L’Hirondelle, Archer Pechawis, Sheila Urbanoski, Adrian Stimson, and Elwood Jimmy.

Âhasiw had passed on in 2006 from AIDS complications and his early new media work was some of the most important Indigenous work in the medium. In this project the idea was to bring together artists and curators who had worked with him and knew him. Several worked on his original pieces, so bringing together this group of artists and arts professionals allowed us to produce a site that really pursues and expands his ideas against the backdrop of his archive.

The impact of this particular site has been profound in many ways. Because most of this work was not accessible or was hidden in various websites, bringing all this material together had an important impact. Other organizations produced exhibitions based on the research that was available on the site. Exhibitions of his work sprung up at ASpace, NeutralGround, and Urban Shaman, located in communities where Âhasiw had worked and using source material we made available through the Ghostkeeper project.

Dana Claxton, Tree of Consumption (1992). Part of the First Nations Performance Series. Photo by Merle Addison.

Other sites focused around individual programs. The 2002 conference Indian Acts brought together Indigenous performance artists from around the continent to talk about the medium. This was the first gathering of performance artists at this scale and the curators here included the conference curator Dana Claxton and curator Tania Willard who had curated Beat Nation earlier at grunt, and later as a touring exhibition with the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Curator Christine Stoddard produced the site Queer Intersections looking at queer performance and cabaret at grunt and elsewhere during the heyday of identity politics. TL Cowan’s text situates the identity politics of the 1990s in relationship to marginalized culture within a context of current queer theory. Stoddard did a group interview with Paul Wong, Laiwan, and Archer Pechawis, further contextualizing it within the communities that produced the work.

Other sites dealt with community-based work and social practice, sculpture, and writing as points of intersection between today’s artwork and that of the past. ATA—Activating the Archive was successful in engaging youth and other audiences in the archives at grunt, both in their physical form and in their online digital manifestations. At grunt it started our work in the gallery’s archive, and we have maintained a steady volunteer program ever since. In this program, students and others work in our archives weekly, digitizing material, uploading it to the archive, and constructing posts on social media about the material. Over time we recognized that the archival posts on our Facebook page had three to five times more views, likes, and shares than the posts from our regular program. The archival material had a much farther reach, though we are still speculating as to why.

ATA spawned a lot of programming over the next five years and made archives an important part of what we do. In 2011, Michael DeCourcey, a prolific Vancouver photographer since the days of Intermedia, put documentation of an early conceptual project—Background Vancouver, which he did in 1972 with artists Glenn Lewis, Gerry Gilbert, and Taki Bluesinger—online. They traveled separately through Vancouver taking photographs, a selection of which DeCourcey later made into a large silkscreen print. The photos struck a nerve around how much Vancouver had changed over the period. At grunt we used this as a basis for a project commemorating the project by redoing it with emerging artists. The three artists, Igor Santizo, Emilo Rojas, and Guadalupe Martinez, produced This Place/Vancouver after they were commissioned to produce a performance on 30 October 2012, exactly 40 years after the original project. Santizo, Rojas, and Martinez were all from Latin America. Igor had come here in the Guatemalan diaspora during the 1980s. Emilio, from Mexico, and Martinez, an Argentine, both were doing graduate degrees at UBC’s Fine Arts program.

This Place/Vancouver was the result. The performance on the day followed DeCourcey’s maps around Vancouver, but the artists stayed together rather than moving separately through the city. They used video to record their travels, using the audio capabilities as well as the images. They stopped for lunch at the Naam, a vegetarian restaurant that has been around Vancouver for many years and was a site in the original project in 1972. Artists Michael DeCourcey and Glenn Lewis joined us for lunch. The discussion ranged from the original project to present-day Vancouver and the gentrification that was rapidly changing the city.

The website produced the next year in May 2013 included an interactive map that showed the three original routes and the 2012 route overlaid on Google Maps and allowing the visitor to upload materials. The exhibition included the 1972 print by Michael DeCourcey and was accompanied by a series of four discursive events that animated the project. The first was on Social Cartography with Am Johal and Sarah Samash. The second was a discussion with DeCourcey and Lewis, led by VAG curator Grant Arnold. Arnold had been the Vancouver curator of Traffic, a Canada-wide retrospective on conceptual practice across Canada. The third was a sound walk led by Vincent Andrisani and Randolph Jordan. The final event was a discussion with Santizo, Rojas, and Martinez.

The project focused on a changing Vancouver, but because the artists were all immigrants, it gave a different focus to the project. The conceptual practices of 1972 came face-to-face with the social practices of 2013. And because of DeCourcey and Lewis’ participation, the project became intergenerational, including artists from their 20s to their 70s, spanning a range of Vancouver practice over 40 years.

Mainstreeters: Taking Advantage 1972–1982, exhibition curated by Allison Collins and Michael Turner, 2015. Photo by Henri Robideau.

In 2014 grunt celebrated its thirtieth anniversary with two projects that both referenced the archive. Julia Feyrer’s piece The Kitchen recreated the grunt kitchen in the gallery as a place to review the archives and the space. The kitchen at grunt had been a social space throughout our history, but by 2014 it no longer existed as a kitchen after having been replaced in 2011 by our media lab, so the exhibition was a nostalgic look at the facility. Throughout the six weeks, Julia pulled different material from the archive that spoke to the space as social space and the kinds of interactions that went on there.

We also produced an ebook for our anniversary called Disgruntled—Other Art that reprinted a series of texts from our archives, selected by art historian Audrey MacDonald and founding member and editor Hillary Wood, and epublished by Renee Mok. The ebook reprinted a series of essays over our 30 years that outlined a history of the gallery through the artists, curators, critics, and social commentators who wrote about it.

Our next project was Taking Advantage—the Mainstreeters, produced in early 2015 after a two-year period of production and research. Curators Allison Collins and Michael Turner worked in Paul Wong’s archive for a period of over 18 months from 2013. The Mainstreeters were a Vancouver group of artists who were influential in the early art history of Vancouver.

Mainstreeters: Taking Advantage 1972-1982, exhibition curated by Allison Collins and Michael Turner, 2015. Image donated by and courtesy of Tatsuo Kage.

Consisting of Paul Wong and his high school gang, they produced photographs and video; later several were founders of Video Inn with Paul. As one of the first groups of artists with access to PortaPacks, they used video as an early form of social media in ways that can still be viewed as audacious. During the curators’ research, they selected 4000 images and 40 videotapes that were then digitized during the course of the project.

By 2012, Vancouver’s Main Street had been branded by a whole new generation of hipsters. The culture is ubiquitous in the coffee shops, small bars and restaurants along the street, and in the small shops peppered between the antique stores and Vancouver fashion outlets. Taking Advantage looks back at Main Street when it was not the hip neighbourhood it is now, but was a working-class district that is the main dividing line between the very class-different east and west sides of the city. Also in works such as the performance/video FOUR, these artists create a prototype of working that uses their own lives as backdrop for a showdown between the four women in the project. A forerunner of reality TV, the work employs a “forced reality” that TV viewers have since come to know so well.

The final project consisted of an hour-long documentary on the artists accompanied by a website that displayed further media. The documentary was released on social media six weeks before the exhibition, and the web site went live when the exhibition was opened. Originally initiated at grunt, we connected with Presentation House Gallery and Satellite Gallery to co-present the exhibition. Presentation House also later developed a publication, released in 2017.

There was also a robust program of engagement events, including the re-enactment of the 1970s performance piece Camp Potlach, a tour through the neighbourhood led by Mainstreeters Paul Wong and Annastacia MacDonald, a drag ball at the Fox Cabaret, a curators’ tour of the exhibition, and a conference presented by Presentation House Gallery placing the work in the context of other work from the same period. As well, a series of four video installations were installed in the windows of shops on Main Street for the duration of the exhibition.

Over the last few years there has been a shift in our archives activities to not just hosting curators, scholars, and students in our archives, but to also supporting projects that explore other archives such as Mainstreeters.

For the 2015 project Arctic Noise, artist Geronimo Inutiq worked in the IZUMA archive at the National Gallery to create an installation as part of the ISEA Conference in Vancouver. Curated by Yasmin Nurming-Por and Britt Gallpen, the exhibition later toured to Trinity Square in Toronto and Paved in Saskatoon. In Vancouver it was coupled with the conference Terminus: Archives, Ephemera, and Electronic Art, a one-day workshop at VIVO hosted by Ethnographic Terminalia, an international group of digital anthropologists who do regular projects around digital technology and archives.

In 2017 we initiated the project The Making of an Archive with artist Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn and curated and produced by Vanessa Kwan and Dan Pon in collaboration with Maiko Tanaka. A Press Release on the grunt website (http://grunt.ca/the-making-of-an-archive/ 16 December 2017) explained:

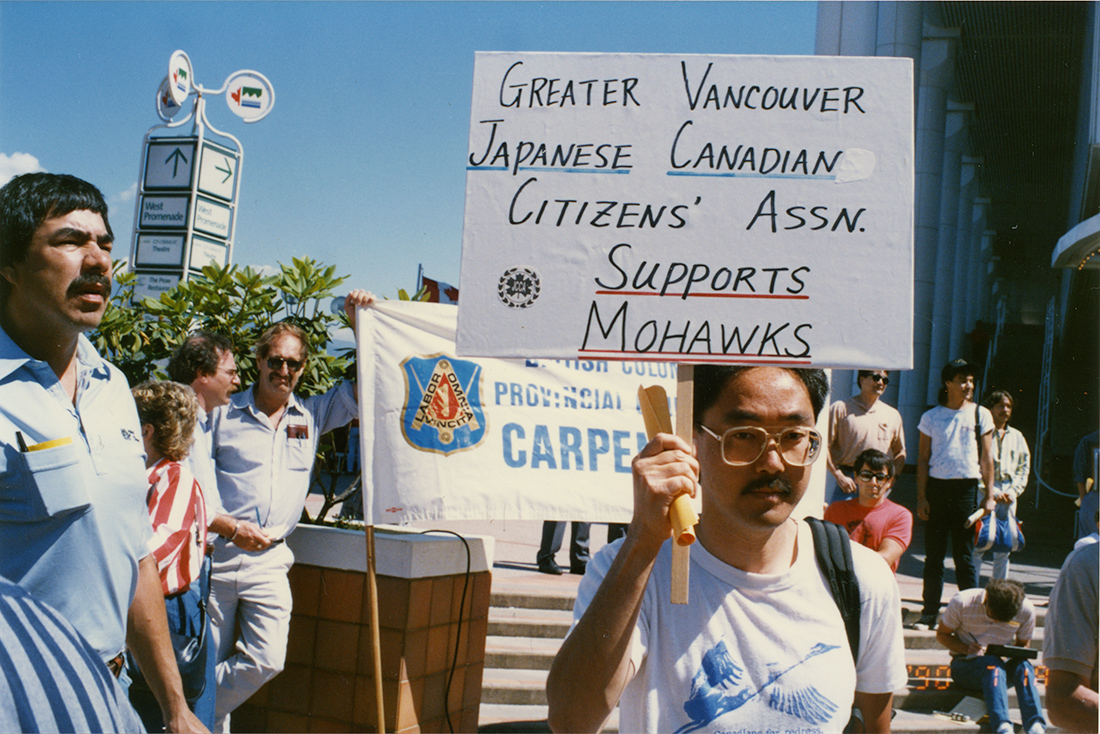

There were two main catalysts for the initiation of Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn’s project, The Making of an Archive. One was the photo albums of the artist’s father, an amateur photographer who took countless snapshots of his daily life when he first immigrated to Canada in the ’70s. The second was the research Nguyễn did for 1967: A People Kind of Place, her sci-fi documentary and part of her project Space Fiction & the Archives, created out of archival material the artist found of Canada’s centennial, which celebrated the implementation of the country’s point-based immigration system. Her research into various national archives for the film—from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the National Film Board and the Library and Archives Canada, in Ottawa—turned up surprisingly very little under searches for “multiculturalism” and hardly any evidence of the everyday lives of immigrants in Canada who came to live under this new system.

The project originated at Gendai Gallery as a series of digitizing workshops at the New Canadians Centre, Art Gallery of Ontario, Aga Khan Museum, Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts, and Artspace, and featured in their publication Model Minority. Originally curated by Maiko Tanaka, curator Vanessa Kwan brought Jacqueline to Vancouver to produce of a series of digitizing workshops in conjunction with the Powell Street Festival, The Carnegie Centre, and the Richmond Art Gallery. There were also a series of private digitizing sessions at grunt with various people who reached out through social media.

Engagement events with UBC’s Belkin Gallery and a publication including writing by Liz Park, Maiko Tanaka, Gabrielle Moser, Vanessa Kwan as well Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn in conversation with Fatima Jaffer, and Tara Robertson in conversation with Dan Pon are still to come. Hoàng Nguyễn has plans to continue the project in Sweden where she currently resides. The project has brought out histories of social justice activism, and engagement and solidarity with the immigrant communities that often are missing from the official multiculturalism narrative. This allows for a much more dynamic and engaged picture of multiculturalism that includes activist and queer histories that reach back decades. Again, the intergenerational transfers of information that happens in these exchanges are hard to imagine in other contexts.

These projects have existed in the backdrop of other artists’ archive activity in the city, most significantly at the Western Front and VIVO, but also at UBC’s Belkin Gallery, where Associate Director Lorna Brown has made a significant contribution through her current programming as well as with the previous Ruins in Process. In 2015, Western Front, VIVO, and grunt produced their first Archive Week, where we developed programming from our archives and ran concurrent programming and marketing. In 2017 the Belkin Gallery at UBC got involved and also 221A, and these groups are currently in planning for an event later in 2018.

The Belkin Gallery has been an important player in artist-led archival development under Associate Director Lorna Brown. Brown led Ruins in Process—Vancouver Art in the ‘60s in 2009 and it was an integral step in developing the process. By creating a team that interfaced with artists’ archives and collections, the project was robust and dynamic in ways that art historian-led enquiries seldom are. Her current project on 1970s feminist and activist histories that began with the current exhibition, GLUT, is an important link between artist- run centre archives and the institution. Working with a host of other organizations she has been able to access histories that are not often known or available.

The impetus behind Archive Week is to bring attention to the work being done in artist- run centre archives and smaller archives in general in the city. Each group has developed their own projects, with collaboration on several. They have been able to attract academics and archivists from across the continent including Kate Hennessy, Trudy Smith, Ethnographic Terminalia, Christy MacDonald, Kristin Dowell, and Shannon Lucky, who have all participated in the programs.

The audiences for Archive Week were distinctly different from the regular audiences for our programming, in that it attracted more librarians and archivists and artists who use archives regularly in their work. In many ways the archives in artist-run centres mirror the approach of ARCs in general: they stood in opposition in some ways to the formal and institutional protocols of infoscience in the same ways that ARC programming stood in resistance to the methodologies of the museum and public art gallery. The ARC archives employ a more open approach than is usual in most archives, not only in terms of repurposing materials and reinterpreting them, but also by allowing open access to the public. The flexibility of the ARC archives allowed for possibilities more difficult or impossible under the usual restraints of infoscience protocols.

Al Neil, 1989. Image part of The Blue Cabin Residency. Photo by and courtesy of Jim Jardine.

Archive Week allowed for a national interface between others working on ARC archives across the country, such as Christy MacDonald, who worked in digitization and archives at VTape and other spaces in Ontario, and info-academic Shannon Lucky, who had worked with prairie ARCs around archival development. Through ATA, grunt has worked quite closely with VTape in Toronto, where we have an ongoing relationship around archives. Our archivist, Dan Pon, did a six-week residency at VTape, and the VTape digitization lab, until recently, was run by Brian Gotro, a Vancouver artist who was one of the core team of ATA. These interfaces are invaluable in bringing new knowledge into Vancouver and getting word of our achievements outside of the city.

Through our projects in the archive and social media, as well as volunteers sharing their explorations in the archives, we started to notice the strong response they were receiving. Our archive posts got between three and five times more viewers, likes, and shares than content from our regular program.

As well, the volunteer program that exists around the archives brings five to eight volunteers working weekly in our archives, mostly on digitization projects or their own research. This represents the largest volunteer donation of time outside our board in our organization. Many are students and independent researchers among them who take away knowledge of our archive that often results in exhibitions not connected to grunt gallery at all. This regularly results in other researchers accessing our archives on a shorter-term basis, and the increase of influence of our archives has been substantial.

But it is through the programming that the archives really come alive. Currently, besides The Making of an Archive, we have several other programs that encompass archives. Vanessa Kwan is working on a project with Syrus Marcus Ware placing him in a residency at the Trans Archive in the University of Victoria, which resulted in an exhibition at grunt in October of 2018.

As well, we are working with Rebecca Belmore’s archive to produce the publication Wordless—The Performance Art of Rebecca Belmore. It will act as the catalogue to an exhibition of her performance work at the Audain Museum in Whistler in April 2020. Included in the project is a remake of her website that we originally put online in 2007.

There is no doubt the archive has expanded the programming at grunt in ways we didn’t always envision, each project creating new archives which make their way into the world. In this era of social media, events and exhibitions are immediately archived, which may explain a lot of archives’ relevance in the current period. Whether they are projects grunt initiates such as ATA or Mainstreeters, or projects where we work in tandem with others such as with Arctic Noise, This Place Vancouver, or The Making of an Archive, they all speak to the currency and relevancy of the archive in this moment. The archive as site of activation and engagement is important to this development and changes the ways we look at the past.

A current project grunt is working on is the Blue Cabin Residency with partners Other Sights for Artists Projects and Creative Cultural Collaborations. In 2015 we saved an early twentieth century squatters cabin in North Vancouver and plan to put it on a floating platform, with a tiny house as an artists residency. Originally the home of artist and jazz pianist Al Neil and his wife artist Carole Itter, the cabin holds histories of its creation in 1927 and its move onto the Dollarton foreshore in 1932. The project brings together a number of histories including First Nations, squatters, labour and maritime industrial histories, as well as the cultural and artistic histories that are all embodied in the project. The project allows an interface between the heritage and cultural communities that is rare, and the participation and support of people like Heritage Planner Hal Kalman and North Vancouver Archives Director Nancy Kirkpatrick give the project a wider interest than just within the arts community.

In 2017, artists Jeremy and Sus Borsos spent six months refurbishing the cabin using historical materials, and documenting meticulously the process and what they found. The history of the cabin was laid bare and when taking up the floor they discovered over 30 posters from 1927 put under the wooden floor as insulation against squeaking. The posters in various states show a history of theatre, music, vaudeville, cinema, and sporting events from the period. The Borsos’ documented as they went, taking 4000 photographs of the process that, together with the historical photographs and documentation of its various moves, has created another archive at grunt. Through the residency, we expect this archive to become larger as we move forward. In June 2018 Jeremy mounted an exhibition of the process at grunt.

Editor’s note: In 2018, Glenn Alteen, grunt’s founder, curator and program director was awarded the Governor General’s Outstanding Contribution Award. He will retire in 2020 after working with the artist-run centre since its establishment in 1984.