Niranjan Rajah, Zainub (Untitled), Leraian (2019). Digital Image, 50.8 x 76.2 cm Silver-Halide Dye Print. Courtesy of the artist

Niranjan Rajah

ZAINUB VERJEE: FROM SIGNIFIER TO SIGNIFIED

ZAINUB VERJEE BEGAN HER CAREER in the vibrant Vancouver arts community of the 1970s which was steeped in interdisciplinary, intermedia, and intercultural practices. The scene was set by the synergy and tension between the experimental and ephemeral approaches of the international Fluxus movement as embodied in the Western Front on the one hand, and on the other, the highly reflexive photo-conceptual approaches of the Vancouver School.1 The mix of values of this milieu seem to have informed Zainub’s nascent ethos. Zainub has taken bold and challenging positions on questions of aesthetics, access, technology, and artists’ rights through her art practice, critical writing, institution building, distribution activities, programming, policy work, and leadership. Indeed, many of her early concerns have since become formative themes of the Canadian cultural sector. In this essay, I approach the subject “Zainub Verjee” quite literally as a “representation,” and also figuratively, as an “impression created in the public consciousness.” In short, I approach Zainub as an image.2 I present and articulate various images of Zainub, including an image of Zainub in my own artwork. I also reflect on the impression she has made upon national and global communities of contemporary art through her wide-ranging practice.

This essay is structured on the duality of the Saussurean sign. In it, I articulate the changing significance of Zainub’s image as it spans the space and time between my photographic art work Zainub (Untitled) (2019), and that of an earlier representation in an art work by Ken Lum Untitled (Zainub) (1984). Saussureian linguistics introduces the notion of a synchronic dimension to the workings of language in which the meanings of words and, by extension, of images expressed in a given speech act (la parole) depend on the wider system of language (la langue). Saussure develops the concept of a bimodal “sign” which presents a loose and contextual relationship between a materially generated “signifier” and a conceptually realized “signified.” In this new approach to language as a system of “signs,” that which is “signified” is determined both by the position of the “signifier” within a particular parole and the state of the langue at the time of its expression.3 Saussure limits the abstraction and multivalence of this bimodal sign by setting it within the palpable socio-historical consciousness of a community of speakers (masse parlante) to which it must belong. In his own words, “Language is no longer free, for time will allow the social forces at work on it to carry out their effects. This brings us back to the principle of continuity, which cancels freedom. But continuity necessarily implies change, varying degrees of shifts in the relationship between the signified and the signifier.”4 The present writing is an exposition on shifts in the relationship between signified and signifier in the image of Zainub Verjee.

My artwork Zainub (Untitled) arises as a response to an unexpected encounter with Ken Lum’s Untitled (Zainub) which belongs to the M+ Collection in Hong Kong. Zainub (Untitled) is part of a set of twelve images that will comprise the upcoming Leraian (Denouement) series which is itself a part of the expansive Koboi Project (2019).5 This project has an overarching narrative that can be summarized as follows. My alter-ego, the diasporic Koboi, returns from his place of domicile in Vancouver to his kampung halaman (place of identification) in Kuala Lumpur where, he explores his cultural identity as a Tamil, while also acknowledging its dilution and dissolution. Koboi begins to understand that his home is, in fact, constituted in a network of relationships. While he stakes his claim in Southeast Asian art as a Malaysian Indian, Koboi reflects on his migration to native Indian land in North America. He travels widely and identifies as a citizen of the world, while simultaneously finding his place in the Canadian landscape. Koboi wonders, as he wanders the world, if in fact, he has been at home all along.

It is among the personal and professional signifiers of this autobiographical Koboi Project that my Zainub (Untitled) takes its place. In this image, I present Zainub Verjee as a friend, as a predecessor in diasporic wandering, and as a prominent figure in Canadian art. I first met Zainub in 2004, soon after I immigrated to Canada. I was convening a conference for the New Forms Festival at the Vancouver Art Gallery and, as a means of contextualizing this large international media arts forum, I was in the midst of creating a post-traditional theory. This interpretive framework threaded together a multiplicity of global and local perspectives with a view to articulating relationships between postmodernity, technology, and tradition. At that time, Zainub was a Senior Program Officer for Media Arts at the Canada Council for the Arts. She supported the festival and conference in that capacity. Her encouragement and critical engagement enabled me to express my new and unfamiliar agenda within the mainstream Canadian context.

The conference was titled Old and New Forms: A PostTraditional Technography of World Media Arts6 and the theoretical framework I developed forms the basis of my praxis to the present day. That encounter confirmed for me the indispensability of enlightened art administrators and introduced the particular role that Zainub Verjee has played in advancing the cause of progressive and internationalist approaches in Canadian art. Subsequent encounters with Zainub have confirmed my initial impression. Working with as much regard for the centre, as for the periphery, her modus operandi has been to develop platforms for the disparate entities of the Canadian artistic community, thereby enabling an efficient, transparent, and ethical framing of the whole. In her own words, “it is always a question of building coalitions and alliances.”7

Okuwui Enwezor has noted, in the context of Documenta 11 (2002) that, “Today’s avant- garde is so thoroughly disciplined and domesticated within the scheme of Empire that a whole different set of regulatory and resistance models has to be found to counterbalance Empire’s attempt at totalization.”8 It is my estimation that early in her work as a practicing artist, Zainub had independently identified the same need for “regulatory and resistance models” and as she developed her career in arts administration, she has worked to leaven effective space within the Canadian art system for the feral innovation and dissent, the absence of which Enwezor seems to lament. She has channeled these disruptive artistic

Zainub Verjee, Ecoute, S’il Pleut (1993). Single-chanel Video, 07:34 minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

energies towards achieving change at the heart of Canadian art, while simultaneously acquiescing to some degree of functional harmony for the whole.

While she has contributed to diverse aspects of art and culture, Zainub has made her most significant contributions in the realm of media arts. She has exhibited her work at the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Venice Biennale. The epitome of Zainub’s enmeshment in the artistic milieu of her home on the Northwest Coast is the inclusion of her video work Ecoute, S’il Pleut (1993) (Listen, if it is Raining) in Road Movies in a Post- colonial Landscape in 1997. This exhibition was curated by Judith Mastai at the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art and was the British Columbian component of the three-part series titled Traversing Territory which also covered Washington and Oregon in the USA. These exhibitions explored developments in contemporary art on the West Coast that were emerging outside of the institutional frame. Traversing Territory II presented work from Zainub and nine other artists including the Vancouver School luminaries Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham, and Ian Wallace.9

Ecoute s’il pleut is, as the catalogue entry in the Vtape video archive outlines, “a video poem which explores time and space allowing the viewer to experience a moment and the fullness of silence. The camera moves across patterns of leaves and falling water. A woman sits pensively beside a fountain; a child floats slowly past a monument.”10 This piece transposes the poetics of water and space from the inner courtyards of Islam onto Montreal’s urban gardens. Laura Marks captures the metaphysical essence of this work in

Zainub Verjee, Through the Souls of My Mother’s Feet (1997). Four-channel video installation, Burnaby Jamatkhana, 1997. Image courtesy of the artist.

her essay in “North of Everything: English-Canadian Cinema Since 1980” thus, “Zainub Verjee’s gentle Ecoute s’il pleut allowed the viewer to experience silence, full as a drop trembling on a leaf, for eight minutes out of ordinary time.”11 At the same time the use of text as a gloss to the moving image, offers the possibility of wider associations, perhaps even alluding to the extrusion, through language, of the image of the nation onto the landscape.

Tea for Three (1995) was a mixed media installation that was presented as part of the TransCulture exhibition curated by Montreal-based Oboro Gallery for the 100th anniversary of the Venice Biennale in 1995. This work was made in collaboration with Susan Edelstein and composer Robert Cartwright. The Oboro Gallery was selected by curators Fumijo Nanjo and Dana Friss-Harness, for the World Tea Party that developed the notion of tea as an ancient metaphor for communication, sharing, and coming together.12 In a review of the installation’s second presentation in Vancouver, Robin Laurence describes the piece as, “consisting of a computerized piano playing a composition by Zainub Verjee and Robert Cartwright and surmounted by wooden boxes. The boxes contained porcelain plates with text and engraved silver tea spoons on beds of fragrant tea leaves and addressed a poetic cluster of social issues.”13 Once again, the work presents itself as poetry, while its poesis seems imbricated with an acute criticality.

As a media artist, Zainub seems to have been moving along with both regional and global currents. In 1997 she produced a four-channel, eight-monitor video installation titled Through the Soles of My Mother’s Feet. Her piece was presented by Burnaby Art Gallery under the rubric of Tracing Cultures, an exhibition series that aimed to address notions of cultural hybridity and communication through difference. Zainub presented her installation at the Jamatkhana Ismaili centre in Burnaby. Built in 1985, this Jamatkhana was the first Ismaili Mosque in North America. It is a deeply symbolic site for the community. After extended discussions between the artist, the curators, and representatives of the venue, the work was installed in this delicate community space, raising social, cultural and aesthetic associations and meanings that would not have been indexed by a gallery presentation.14

Through the Soles of My Mother’s Feet was developed over a period of four years beginning in 1993. The work centered on the idea of a nomadic architecture indexing the physical and social structures that people carry with them to maintain communal coherence over space and time. It presents personal memory as a reflection on a communal migration from Gujarat to Kenya and on to England and Canada. Addressing bodily, spatial, and territorial notions of culture, this migratory tale is like the earlier Ecoute s’il pleut, a video representation of the sensual experience of place as it affects memory and identity. The video component of eight minutes is layered with a soundtrack of 16 minutes such that the rhythms of the piece reflect the octagonal form of the architecture of the Jamatkhana. It can be said that Zainub was an early adopter of the auto-ethnographic methods that would become the norm for reflective, subaltern artists throughout the 1990s. This is what Hal Foster had theorized as the “ethnographic turn” as he describes and prescribes the “return of the repressed” post- colonial subject. By contextualizing Through the Soles of My Mother’s Feet in the traditional space of the Jamatkhana, Zainub achieves Foster’s postmodern “self-othering” while skilfully eschewing, even problematizing, the pitfalls of what he pejoratively called “narcissistic self-refurbishing.”16

Having made her mark as an emerging Canadian artist in the 1980s and 1990s, Zainub shifted her emphasis to the administrative and policy arenas. This reorientation should be appraised in terms of Zainub’s possible motivations as well as the contemporaneous developments in art practice and theory. As the locus of aesthetic contemplation moved out of the art object and into process, installation, performance and idea, curatorial and administrative modalities began to take on a more overtly creative function. There emerged in this interpenetration of artistic and administrative purviews, opportunities for new kinds of practice. With reference to curatorship in the 1970s, and with particular mention of the activist curatorship of Harald Szeemann, Michael J. Kowalski notes, “Since the curator has traditionally occupied the strategic ground where the theory of the critic meets the praxis of the art maker, the curator was ideally positioned to step to the fore when the idea-versus- object dichotomy began to collapse in the work of Duchamp.”17 As curatorship and administration became fields of contestation and innovation, Zainub entered this arena. She brought the insight, creativity and criticality of an artist to bear on the institutional tasks of introducing, promoting, and raising the profile of Canadian visual and media arts.

It could be said that Zainub brought “institutional critique”18 into the workings of the institution itself. Jennifer Snider argues that the Canadian artist-run centre “is a specialized embodied expression of the institution as apparatus” and that it is a “form of and forum for institutional critique.” She argues further that the administrative role in the artist-run context is both critical and analytical, as “the administrator assesses and supports nuanced and alternative approaches to normative (capitalist, hierarchically corporate) socio-political interactions inside and outside the art institution.”19 Simon Sheikh, in turn, invokes Benjamin Buchloh’s, critique of the idealism and hubris of conceptualism in Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions, as he argues that the 1980s saw the expansion of the institutional ambit to include the artist, performing a critique of the institution, as an institutionalized subject. Sheikh asserts, that such critical modalities have, since their inception, been absorbed and incorporated into the institution and have been assimilated as part of the broad social practices of contemporary art. He notes that consequently, institutional critique has come to require the modifying of the institution itself as a dynamic site of expression.20

From the critical placement of Through the Soles of My Mother’s Feet outside the gallery, it is clear that Zainub’s art was responsive to imperatives of institutional critique. However, while the artist might have the opportunity to intervene in the structures of representation, only the administrator is in a position to modify the institutions that produce and present the objects and encounters of this representation. In Buchloh’s words, it is these institutions that “determine the conditions of cultural consumption.”21 Given the rise in the awareness of the assimilative power of the institution, and in the growing sense of curatorial agency, it is not surprising that Zainub was drawn to policy work and administration as a means of achieving her critical agenda.

I suggest that Zainub’s career in curatorship, policy and administration has been consistent and contiguous with what might be termed a critical transversal aesthetic. “Transversality” is a term developed by Felix Guattari at the juncture of politics, psycho- analysis, and theatre. It is, in Guattai’s words “a dimension that strives to overcome two impasses: that of pure verticality, and a simple horizontality. Transversality tends to be realized when maximum communication is brought about between different levels above all in terms of different directions.”22 Giles Deleuze develops this notion as a literary lens in the course of his reading of Marcel Proust. While the conventional literary text is “logocentric” in that it indexes a stable and transcendent world of referents, Proust’s reminiscences constitute a relational text of subjective associations that evoke “an originating viewpoint.”23 In Deleuze’s transversal reading of Proust, the presupposition of objective representation is displaced by first person fragments that unify into a particular view of the world.

Transversality can thus, be seen as an excess or overflowing of Saussure’s contextual construction of language, beyond the binary logocentrism of structuralism, into an unstable post-structuralist phenomenology of meaning. Deleuze esteems this Guattarian concept as being of political importance because it articulates the basis of “non-hierarchical relationships.”24 Susan Kelly applies this transversality to the problematic relationships between political and artistic activities but, like Simon Sheikh, she worries about the assimilative power of the institution. She explains “how despite the purported de- territorialising actions of transversal practices, what … is now ‘visible’ is more often than not, an ever-expanded category of (relational, socially engaged) art. In fact, one could say, that it has become nigh impossible to make a work of art that is not a work of art.”25

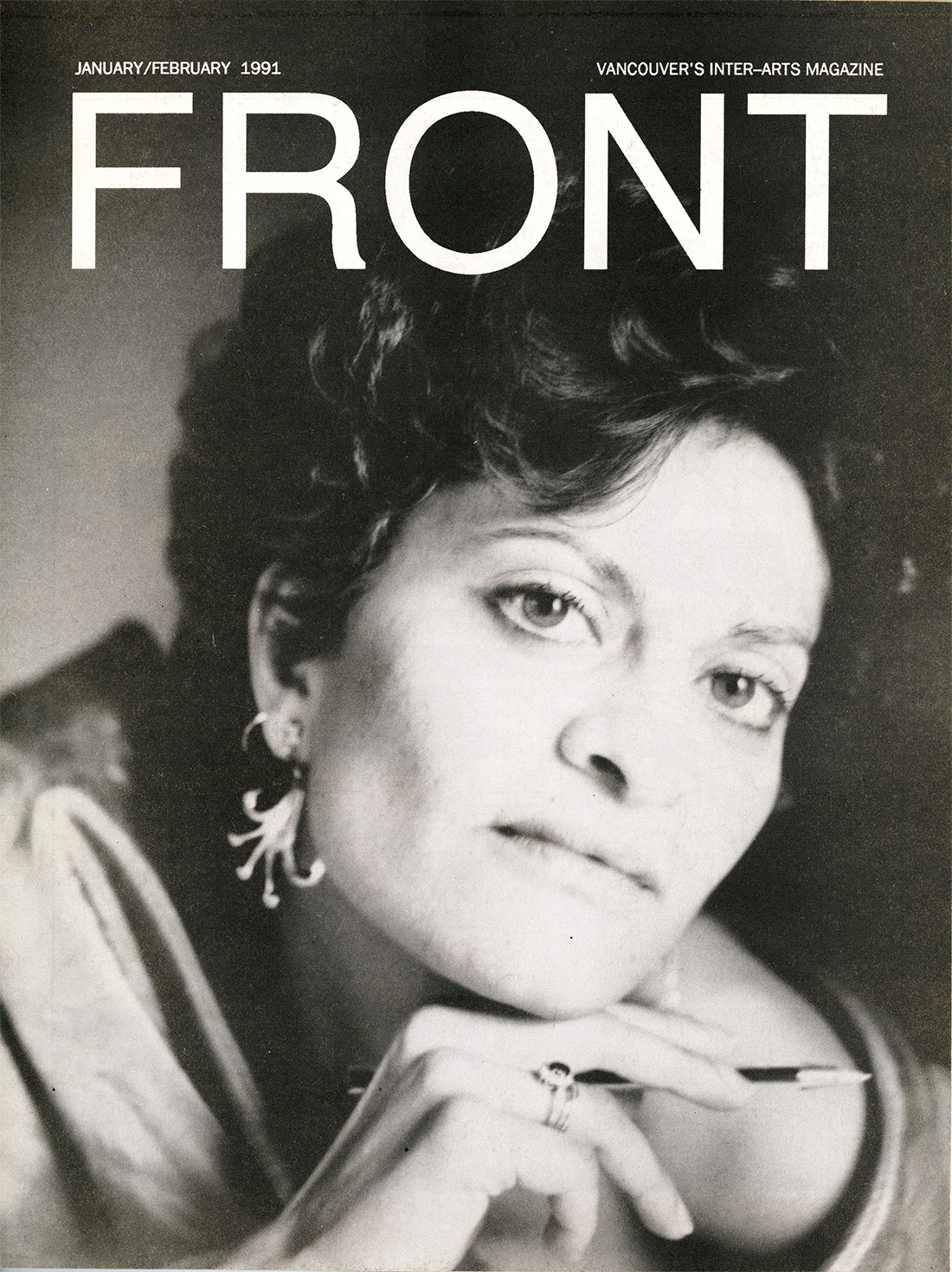

In the light of this institutional ability to denude critical art works of their politics and power, one might interpret Zainub’s movement, from art to institutional work, as the pursuit of a more effective transversal praxis. Zainub’s interventions in her wide-ranging career might come under Sinder’s rubric of “a performative practice of embodied institutional critique.”26 In 1991, the exhibition titled Fabled Territories—New Asian Photography in Britain opened at the Vancouver Art Gallery to great controversy. This historic exhibition organized by Sunil Gupta and Sutapa Biswas was the first contemporary show of South Asian artists to be held at the Vancouver Art Gallery (VAG).27 It must be noted that 1991 seems to have been a year of recognition and inclusion in the Canadian art world. In the same year, a national touring exhibition titled Yellow Peril Reconsidered curated by Paul Wong presented works in photography, film and video by 24 Asian Canadian artists. The show aimed “to present new and challenging work, moving it from a position of marginality and placing it in the forefront of attention.”28

Like Yellow Peril Reconsidered, Fabled Territories, originated as a response to the gallery system. South Asian artists who felt excluded by the British mainstream curated their own show to create visibility for themselves. The irony of the Fabled Territories exhibition at the VAG was that, when it was brought into the Vancouver community, only token opportunities were afforded for dialogue with local artists, particularly with the local South Asian artists, who were experiencing the same exclusionary conditions. The Artists’ Coalition for Local Colour, a diverse group of local artists and organizations fighting for access, accountability and change, took up a position of protest.29 The coalition centered its protest on the fact that the VAG did not host an opening event for such a historic and culturally significant show and, more sharply, that VAG did not invite local artists of colour to engage with the visitors!30 The British artists were sympathetic to this cause. One of them, Allan De Souza, wrote at the time:

My feeling of the exhibition was that one of its strong points was its rejection of boundaries …. To hear that this dialogue is being prevented by what appears to be a colonial tactic of divide and rule (in this case between national and international artists) is contradictory to what I believe to be the ethic of the exhibition and certainly to my own practice.31

Zainub Verjee was the spokesperson for The Artists’ Coalition for Local Colour and her press release which was titled “Too little; Too Late,” averred the following:

- The coalition supports and congratulates the south Asian artists from England showing in Fabled Territories show.

- The coalition supported by the visiting artists at VAG were holding an opening and cabaret to mark this historic exhibition. This is a direct response to VAG’s decision to hold no opening or reception for the local South Asian arts community.

- The coalition held a public meeting to address the immediate issue of exclusion but also the larger issues of systemic racism, access, community outreach and accountability at the VAG as they relate to the local artists of colour.32

The public meeting was held at the Tamahnous Theatre, and a panel of artists and cultural work- ers was convened. This panel articulated a forthright critique of the prevailing paradigm of mul- ticulturalism and declared that arts institutions had not kept pace with the changes in society.

Coalition activist Sherazad Jamal writes that in the spirit of the dialogue, VAG’s community programs officer Judith Mastai, curator Gary Dufour, and director Willard Holmes were invited. Holmes acknowledged the presence of systemic racism and deemed it to be symptomatic of the wider society.33 The coalition created a list of structural change recommendations for the VAG. The list specified the need for inclusion at every level of the VAG’s decision-making structure. Precisely, it argued that artists of colour should have representation on the board of directors, and on every committee within VAG’s bureaucratic structure. Ann Rosenburg commented on the meeting in the Vancouver Sun. “Forum organizer Zainub and Sherzad Jamal and others set a laudable standard it is hoped will lead to institutional policies that can bring us closer to achieving a multiculturalism which is not white culture-delivered tokenism.”34

Fatima Khadijah writes that in the course of the meeting, it was noted, by the Director of the VAG, that Zainub was serving on a few VAG committees and that this demonstrated inclusivity. Zainub’s response to this ostensibly meaningful criticism gives insight into what might be called Zainub Verjee’s “performative practice.” Khadijah cites Zainub as follows, “While it is true that specific members of the Coalition were involved in working within the VAG, this did not distract from the institution’s lack of accountability and access. and further, that systemic racism within the VAG was a reality” and that she believed in working “from within and outside the system.”35 It appears that Zainub has been consistently transversal in her practice, be it in bringing contemporary art to the precincts of the Jamatkhana as an artist and as a Muslim, or bringing change to a premier institution by working constructively from within, while at the same time, voicing criticism from without.

Zainub’s media arts programming initiatives range from directing the seminal film festival, In Visible Colours in 1989 to her work on early digital initiatives at the Canada Council for the Arts and the Department of Canadian Heritage. In Visible Colours: An International Women of Colour and Third World Women Film/ Video Festival and Symposium presented over 100 works in diverse formats and genres by women from Canada, Asia, Africa, Latin America, United States, Europe, Caribbean, and the Pacific. Lynne Fernie, programmer emeritus at Hot Docs has observed, “In Visible Colours remains one of the foundational film events in Canada and its history is critical to our conversations today as we continue to struggle with post-colonial aesthetics, identity politics and power.”36 Monika Gagnon’s contemporaneous appraisal of the festival is insightful in terms of its transversal ethos. Gagnon observes that in the In Visible Colours programme:

what emerged was a remarkable sense of differences within the sexual and racial differences that have marked women of colour working in industrialized nations, and of women living and working in the Third World. While the realization of this ground-breaking festival depended precisely on honing in on the shared experiences of oppression, sexism and racism experienced by a global range of women, what the event and the screened works finally evidenced quite clearly, was how these lived realities were each determined by specific social, economic and cultural conditions.37

Bryx and Genosko note that, transversality “draws a line of communication through the heterogeneous pieces and fragments that refuse to belong to a whole, that are parts of different wholes.”38 Zainub materialises this abstraction in socio-political-economic-cultural terms. In Zainub’s own words:

In Visible Colours has etched three defining markers: first, it foregrounded the histories of struggle of the women of colour and third world filmmakers; second, it brought forth the issue of race to the second wave of feminism; and third, it created a new alignment in the emergent global politics of the third cinema.39

That these three targets, were achieved in one event, reveal the pertinence and prescience of Zainub’s programming. Monika Gagnon notes, this time with hindsight, that In Visible Colours “offered an agency to the discourse of the time and was the critical building block for the subsequent interventions of the 1990s across gender, diversity, cultural trade and intellectual property rights.”40

In 1998 Zainub programmed Retro/Desh: Questions of Identity Politics for Desh Pardesh, a pioneering South Asian Arts Festival that ran in Toronto from 1990 to 2001.41 Desh Pardesh was steeped in the queer activism of the 1980s and was the genesis of the South Asian Visual Arts Centre (SAVAC). Retro/Desh was a pioneering critical examination of the film and video practice of Asian artists in the 1990s. It highlighted the concerns and issues of identity politics as well as uses of technology. Within the festival’s ongoing concern with gender, class, sexuality, disability, and race in the South Asian diaspora, Zainub asked, “What historical, political and social contexts have contributed to the formulation of contemporary notions of community? How do these ideas of community manifest as a conceptual and organizational cultural space?”42 Retro/Desh posed serious questions about the nature of community and, more pertinently, about the politics of realizing a community in the social- political arena.

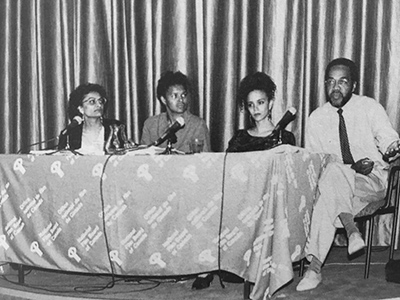

Zainub Verjee with Betty Julian, Coco Fusco and Tony Gittens. Critical Frameworks Workshop, Images Festival, Toronto, 1991. Image Courtesy of Images Festival.

Another early example of Zainub’s programming impact is Media Mirage, produced for the third edition of the Images Festival in 1991. The programme contained independent and community-based work that was critical of the dominant Western media and that presented different images, representations, and histories of Arab peoples, and the Middle East.43 One of the highlights of this programme was the screening of Operation Dissidance— Gulf Crisis TV Project (1991) by Chris Hoover and Simone Farakhondeh. This video was one part of the ten part The Gulf Crisis TV Project (1990–1991) developed by Deep Dish TV and Paper Tiger TV to resist the propaganda build up to the first Gulf War and to voice opposition to the conflict as it progressed.44 Zainub was able to achieve a very timely presentation of a cutting-edge media artifact highlighting the “crisis of representation” which can be said to have begun with Cable News Network’s (CNN) technologically masterful yet partisan and sensationalist reporting during the first Gulf War.45 In the same Images Festival, Zainub joined pioneering media and film artists and activists Betty Julian, Coco Fusco, and Tony Gittens in a public discussion of which Karen Tisch wrote:

the panel was the highlight and held a lively discussion on issues surrounding the exhibiting and marketing of third Cinema. The discussion stressed the importance of audience development; of making work accessible to targeted communities; of having people from within those communities curate the exhibitions and of increasing the critical dialogue that surrounds the work. The panelists raised questions about access to media technology and the opportunity to mediate work, demanding a redistribution of power within the film community.46

Questions of community, access, and diversity can not be addressed in the Canadian context without acknowledging the intractable imposition of the settler state upon the prior nations of Turtle Island. While immigrants jostle with settlers for justice in the present, the Indigenous people of this land fight to recover from colonial wrongs of historic proportions. Despite the desire for reconciliation, the imperatives of the state and of transnational corporations continue to threaten vestigial Indigenous sovereignty and undermine the possibility of a rapprochement. Tamara Starblanket, Co-Chair of the North American Indigenous Peoples Caucus (NAIPC), holds that even the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (2007)47 is ultimately aligned with state interests as the United Nations only recognizes government approved Indigenous organizations.48 Zainub has, in her work, been sensitive to this painful rift in the national polity, and her close personal and professional relationship with important Cree/ Métis media artist, curator and theorist Âhasiw Maskêgon- Iskwêw demonstrates her maxim that it is always a question of building coalitions and alliances. Zainub has written poignantly of this alliance in a memorial text, and I present an extended quotation here in Âhasiw’s memory:

Our musings, often drawn long into the late night, were sustained over cocktail hours, dinners, jury coffee breaks, conferences and meetings of all kinds, and continued over a period of sixteen years.

The subject of these musings varied depending on which exhibition we had seen, conference attended, deliberations that had taken place, cross-community dialogues, appropriation, self-determination, politics of aesthetics, making of subsidized cultures, entitlements versus rights, etc. Grappling with the dominant neoliberal narrative of our world manifesting in the international trade, media, neocolonialism and world religions, Âhasiw mused on a range of ideas: HIV, Food, Drugs and the Pharmaceutical Industry, Political economy of Aboriginal Development; Violence and Poverty; Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity at the United Nations. It was never a clamor but a discourse.

We had spoken of a collaboration of building a tepee with a tribal community in India—something about cultural difference and cultural translation, engagement with cross-community dialogues on self-determination and finding interconnected- ness across social and natural worlds.

All through the musings, I felt as if Âhasiw was tracing how modernity forgets. He roots his forgetting in the processes that separate social life from locality; from the disconnect of consumerism from the labor process; in the morphing and making of urbanisation—the life spaces of modernity. He would conjure the mourning atmosphere talking about the fate of trees as he pointed to the booklet Olive Trees Under Occupation, which documents the experience of the village of al-Midya, a Palestinian village in Ramallah on the north West Bank in 1986 when over 3000 olive trees were uprooted—a metaphor for his experience of uprootedness and the longing for his rootedness.49

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s Zainub contributed to the discourse around diversity and internationalism in the media arts. In a broader administrative capacity, Zainub worked towards setting the media arts within the purview of mainstream Canadian arts institutions. She offered stewardship and sustained engagement through a set of national studies and roundtables which helped to consolidate the media arts. She programmed a year-long series called Out of the Box (1999-2000) in the Canada Council that built media arts literacy among council staff and directors, resulting in a substantial increase in funding.50 As a member of some of the panels, committees and forums that Zainub chaired or facilitated, for instance the New Media Research Initiative Assessment Committee, Canada Council/ National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), 2004, I have personally witnessed Zainub’s commitment to, and advocacy for, media arts within the wider national arts agenda.

As early as in the 1980s, Zainub Verjee had begun to make critical interventions in the emergent scenario that is now identified as global contemporary art. The questions she raised and the programming interventions she made have helped shape the contemporary Canadian interface to this global system. From my own Southeast Asian perspective, the flowering of this internationalism in art, with its diversity of artists and approaches, was led by the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) which began in 199351 and the Fukuoka Triennale which began in 1999.52 These pioneering regional events have been followed by others in Gwangju, Shanghai, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Bangkok. As events like these gained momentum throughout the world in the 1990s, they brought a diversity of artists into the new transnational arena, inserting many of them into a global art canon. This cornucopian presentation of artists to global audiences, involved a new dynamic of power in the selection, financing, presentation and contextualization of art and brought with it a problem of representation.53 There was the assertion of an international postmodern aesthetic by which older national modernisms were dislodged. While artists, previously marginalized by parochial nationalisms, were taken up, others who did not fit the new global aesthetic were excluded.54 As the Fabled Territories episode demonstrates, while the global system brought diversity and helped form new transnational circuits, it also disturbed and displaced local communities. Throughout this period Zainub Verjee developed strategies and interventions that navigated and negotiated this nexus of opportunities and costs.

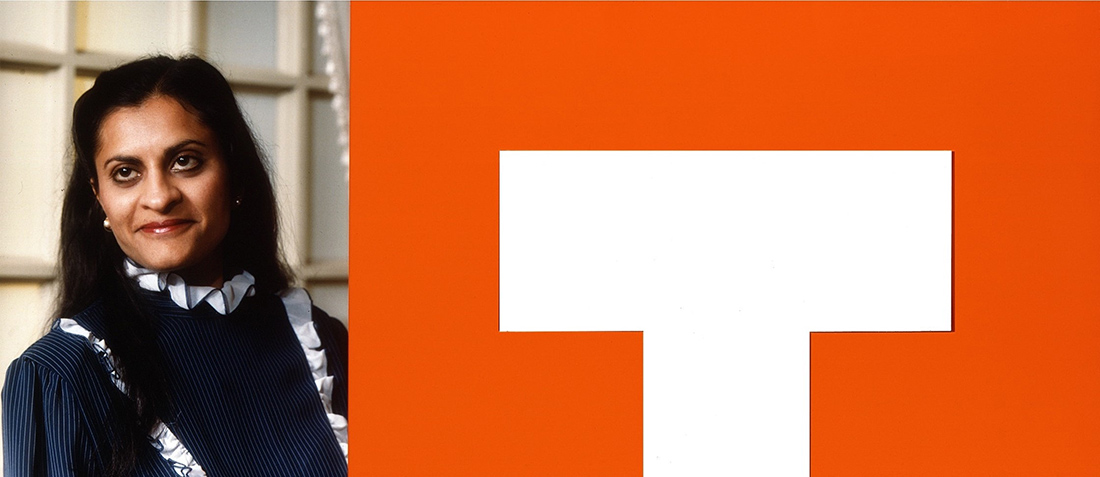

One of the ground-breaking exhibitions of the 1990s was Apinan Poshananda’s Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions55 which opened in New York under the auspices of the Asia Society in 1996. Zainub was part of the ad-hoc advisory committee of

Western Front Magazine, January/ February 1991, Cover Image: Chick Rice. Courtesy of Western Front.

the Vancouver Art Gallery that brought the exhibition to Vancouver in 1997. She was also Director of the Western Front at the time and hosted a residency and performance by Indonesian artist Dadang Chirstanto who was part of the exhibition. The period of Zainub’s directorship of the Western Front, 1991 to 1999, was a critical time of transformation in Canadian art. The Front’s Fluxus-inspired heterogeneity crystalized into the mainstream considerations of diversity we take for granted today.56 The Indonesian artist Dadang Chirstanto’s Western Front residency is indicative of the global reach of Zainub’s contribution to this new institutional transversality. The complexity of this new transnational representational scenario can be glimpsed by reflecting on the transfer of Dadang art and politics from the Indonesian context. Dadang’s work of that period was bravely protesting the oppressive conditions under the military dictatorship of President Suharto and the Western Front’s promotional material describes this work as addressing the paradigms of oppression that structure violence. While the official Indonesian narrative would not have readily endorsed and enabled such work, Dadang was able to rise to the global canon as new transnational criteria now determined the manner in which artists’ representations came into visibility. However, the need to address the broad audiences of the global circuit brought about a simplification of the circulating “signs.” Highly nuanced local signifiers were made to give up communicable global signifieds. The local curators or compradors of these global signifiers had to be diligent, if indeed, they cared to retain the works’ original signification. Even more care was needed if the intention was to generate meaningful dialogical or “translocal”57 meanings in various contexts of presentation.

The Western Front’s promotional material for Dadang Christanto includes a synoptic account, written by curator Apinan Posyananda, of Christanto’s sculptural figures “They symbolized the culture of fear and repression that exists in Indonesia, where the state ideology (panchasila) and the national unification program have transformed the natural cooperation among the people (gotong royong) into the painful sacrifices of voiceless masses.”58 Here we have an example of the condensation of a complex local expression into a global shorthand. The complex struggle between the Suharto regime and that of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is elided, as is the culpability of the IMF’s formula of strict monetary policy and tight fiscal control,59 which must figure in any consideration of the “fear and repression” of the Indonesian people in the 1990s. While Western Front seems to have been a purveyor of this reductive reading of the meanings at the site of origin, Zainub endeavoured to take responsibility for negotiating local meanings at the site of the presentation. She did so publicly in a Symposium on Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/ Tensions in 1997 at the VAG along with Dadang Christanto, Apinan Posynanda, Arjun Appadurai, Imelda Cajipe Endaya, Vishakha Desai, Bhupen Khakkar, Navin Rawanchaikul and other actors on the global stage.60

At the onset of economic globalization, the artifacts of cultural production were treated in international law as “cultural goods,” and fell within the ambit of trade agreements and litigation. As a film and video distributor, Zainub was concerned about the impact of the emerging trade regime especially after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)61 was entered into 1989. Recognizing the threat posed to local producers and to cultural diversity, Zainub partook in a decade-long initiative to develop a legally-enforceable international treaty on intellectual property rights in the context of cultural production. She was associated with International Network for Cultural Diversity (INCD),62 a worldwide network of individuals and civil society groups representing the perspective of creators, cultural analysts, and cultural activists which identified and pressed for the following provisions: that the legal status of the treaty must withstand the erosion of cultural sovereignty brought by global trade and investment negotiations; that it must enable countries of the South to develop their creative capacity and cultural industries; that it must enable signatory States to implement policies to promote local diversity in the face of media and information technologies that impact global cultural production, distribution, exhibition, and preservation; and that it must enshrine the roles of the creative sector and civil society in its administrative mechanisms.63 The UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions was adopted in 2005.64 Zainub also served on the working group on Intellectual Property Rights at the Canadian Heritage and Information Network between 2004 and 2006.65

One of the great costs of globalization is the erosion of local cultures and traditions. Even more troubling than this loss, is the emerging reaction to it, in which nationalist, fundamentalist, and ethnocentric urges have come to the fore.66 In response to this scenario, my Post-traditional theory recasts modernism and postmodernism to retrieve and acknowledge the significance of living traditions. Modernism, which might be caricatured as a monolithic belief in structure and progress, held its own till the later part of the twentieth century when it was displaced by a postmodern culture of fragmentation and relativism. Sociologist Anthony Giddens argues, that postmodernism is simply the late stage of modernism, and that both periods could be subsumed under the rubric “post-tradition.” What Gidden’s post-tradition marks is the dismantling of a traditional order that he casts as being steeped in irrationality and superstition.67 Robert Bellah also uses this term, with which he marks the advent of a more direct Christian spirituality. Like Giddens, he initially rejected tradition for being part of an archaic world, but he later revised this position, to acknowledge that it is only the fact that traditions persist that makes it possible for us to even have a world.68

In my use of the term post-tradition, I index the continuity of traditional beliefs and practices into the modern era. For me, the prefix “post” marks the end of an insular and static view of tradition and points to a rich plurality of living traditions. In my post-traditional theory, diverse traditions persist, cognizant of one another, and modernism itself might be seen as just another tradition. This is the basis of an alternative globalism that I suggest would be more sustainable, as it is more true to the lives of the majority of the world’s peoples. I venture to suggest that Zainub Verjee has long been a globalist in this post-traditional vein. Zainub is of the Ismaili tradition of Shia Islam. Ismailism recognizes the Mawlana Hazar Imam (Aga Khan) as the spiritual leader of an ethnically and culturally diverse global Jamaat or community. Dispersed around the world and yet coherently organized as it is, the Ismaili diaspora epitomizes the notion of a contemporaneous traditional community.

In 2018, Zainub directed the visual arts component of the Aga Khan Diamond Jubilee Arts Festival which was held in Lisbon, the seat of the Ismaili Immamat (a supra-national entity, representing the succession of Imams since the time of the Prophet Muhammad).69 This was a major administrative undertaking consisting of an exhibition, an intensive educational programme, and a symposium. The expansive art gallery presented 135 contemporary and traditional artists from 29 countries. The project was also theoretically innovative in that it integrated the discourses and practices of contemporary art with the

Ken Lum. Entertainment for Surrey (1978). Single-channel video, 01:05 minutes. Collections: Surrey Art Gallery, Vancouver Art Gallery. Courtesy of the artist.

sacred and traditional forms and meanings of the Jamaat. The educational program involved masterclasses, workshops, and portfolio reviews with the aim of giving global access to artists of the community. Zainub revealed her transnational networking and translocal community building prowess in gathering the following Ismaili, Canadian, and international members for the faculty: Christian Bernard Singer, Rozemin Keshvani, Zarina Bhimji, Amin Gulgee, Sara Diamond, Shaheen Merali, Narendra Pachkhede, Bryan Mulvihill, Karim Jabbari, Faisal Devji, Pedro Gadanho, João Ludovice, Yasmin Jiwani, Ilyas Kassam and myself.70

In the course of my youthful wanderings, while I was studying for a Master of Fine Art at Goldsmiths College in the early 1990s, I attended a presentation by Vancouver artist Ken Lum. It was exciting to see his deadpan, post-pop, post-conceptual identity blasting photographic works from the 1980s, but what really struck a chord in me, was his explication of an early video titled Entertainment for Surrey (1978). In this documented performance, Ken stood by the side of a highway for a number of days during the morning rush hour. The attention and honking responses of the drivers diminished as they became familiar with his presence on their route. Towards the end of the cycle, as the responses attenuated, Ken replaced himself with a cardboard cut-out.71 At first Ken was an anomalous and noteworthy presence in the landscape. Then, as he became a familiar sight along that route, one could say that he might as well have been a cardboard cutout and, finally, after the substitution, he was one! While it seemed to me that there were wider connotations of neighborhoods, immigration, race and class issues, what got to me was the clarity with which Ken had marked the transformation of substance into sign.

In 1995, I returned to Malaysia to take a position at the Faculty of Applied and Creative Arts, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. It was a new university built at the height of Malaysia’s

Niranjan Rajah, Zip, La Folie De La Peinture, (1998). Web Art. Courtesy of the artist.

ambitious bid to be a centre in the burgeoning Internet economy. The World Wide Web had just opened Internet communications to the masses and we had world-class infrastructure and information specialists at the university. I had, up until then, been developing a photo/ conceptual/ installation practice and found the multimedia, hypertext, and virtual geography of the Internet a meaningful extension. In 1996, I made a web work titled The Failure of Marcel Duchamp/ Japanese Fetish Even! This piece melded the time, space and intertextuality of the World Wide Web into a critique of contemporary art, culture, and society. In 1998, I made a second web work, La Folie De La Peinture.72 Both these works involved photo-performative actions. The first intervention was at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the second, at the Parc de La Villette, Paris. Both these works involve the marking of the transition from bodily presence into signification. While I did not refer knowingly to Ken’s Entertainment for Surrey at the time, I wonder retrospectively, if my approach may have had its initial stirrings in my reading of his work.

When, in 2011, Ken Lum had his 30-year retrospective at the Vancouver Art Gallery,73 I went with great excitement to catch up with the wider body of his work. I was, of course, hoping that Entertainment for Surrey would be on display. I was accompanied by my family on this gallery visit and somehow, in my excitement, we took a route through the gallery that led us away from the piece. I began to enjoy the rest of the show. Absorbed between this widening attention and the hope of finding the highway piece, I was totally blown away when I turned around in one of the rooms to see, larger than life, and younger than ever, an image of Zainub. Jane, Tara, Durga and I all relished this moment of defamiliarization together. Ken’s art, which had attained its status by parody, pastiche, and inversion of everyday Vancouver kitsch, was itself turned around. In our collectively surprised and sentimental gaze, a high art work had turned into the simple kitsch of—hey look, its Zainub!

I found myself dispossessed of my critical eye—my intense gaze had turned to awkward gape… it was a rare moment for me, the self-assured expert and insider! When I told Zainub of this encounter with her image in Untitled (Zainub), and of my relationship with Ken and his work, she was delighted and explained that there was a greater depth to this wonderful nexus of art and life. She and Ken had been very close in their early explorations of art, its politics, and its aesthetics. They had been together at Simon Fraser University. Neither of them was a student of art then, but they had gravitated together towards artistic expression and critique. They remain close friends and mutually respectful colleagues. This reverse Jamesonian encounter74 with Untitled (Zainub) was the genesis of my own Zainub (Untitled).

Ken Lum, Untitled (Zainub) (1984). Mixed Media: Chromogenic Print, Plexiglas, 101.6 × 228.6 × 5 cm, Collection: M+ Museum for Visual Culture, West Kowloon Cultural District. Courtesy of the artist.

In conclusion, I want to return to the semiological understanding gained from considering Entertainment for Surrey. If the incremental familiarity of a human body standing by the roadside turns its presence into a sign of itself, it seems to me, then, that the growing renown and reputation of a person might have the analogous effect of diminishing the capacity of the photographic image of her body to be a signifier of things other than its person. When Ken made his Untitled (Zainub) it was early in Zainub’s career and her image would not have, except for a very small group of insiders, been denotative of her person. It would, instead, have been a signifier for a range of transversal connotations: ethnicity, gender, and perhaps, class. While the title incidentally informs us that this is a particular person (Zainub), she is not presented as a known quantity and the work’s primary title is Untitled. Over 30 years have passed since Ken’s image was made and “Zainub” is now well known within the Canadian arts community. She has made an impression in the consciousness of a much wider circle than before. Given this alignment of the wider connotations along the axis of this impression, and their consequent accretion to it as a defining referent, I suggest that the figure in the red cowboy hat in my Zainub (Untitled) can only index the very singularly signified—”Zainub Verjee”.

NOTES

- Ken Becker, “Not Just Some Canadian Hippie Bullshit: The Western Front as Artists’ Practice” Fillip, no. 20 (2015): 124–37.

- “Image” in OED Online (Oxford University Press), 10 July 2019, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/91618.

- Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (New York : Philosophical Library, 1959), 65-78.

- Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (New York : Philosophical Library, 1959), 78.

- Niranjan Rajah, “The Koboi Project,” The Koboi Project, 14 July 2019, https://koboiproject.com/

- “Old and New Forms: A Post Traditional Technography of World Media Arts,” New Forms Festival ’04, The Vancouver Art Gallery. (New forms Media Society, 2004).

- Notes from author’s informal interviews with Zainub Verjee, 2018.

- Documenta (Exhibition) et al., Documenta 11, platform 5: exhibition, catalogue (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2002), 45.

- Judith Mastai, “Traversing Territory Part II: Road Movies in a Post-Colonial Landscape,” curator’s statement, PICA / The Art Gym Newsletter, Feb./March 1997.

- Zainub Verjee, Ecoute s’il Pleut (Listen If It’s Raining), 10 July 2019, http://www.vtape.org/video?vi=2237.

- Laura Marks, “Ten Years of a Dream,” North of Everything: English-Canadian Cinema since 1980 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2002), 402–15.

- Ann Duncan, “100 Years up to Date,” Vancouver Sun, June 10, 1995.

- “World Tea Party 1995 Media Coverage, Tea Off, Borderviews,” 10 July 2019, https://thepolygon.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1995-World-Tea-Party-Media-Coverage.pdf

- Notes from author’s informal interviews with Zainub Verjee, 2018.

- Karen Henry, Tracing Cultures (Burnaby: Burnaby Art Gallery), 1997.

- Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer?” Global Visions: Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts, Edited by Jean Fisher, (London: Inst of Intl Visual Arts Symposium), 1994.

- Michael Kowalski, “The Curatorial Muse,” 10 July 2019, Contemporary Aesthetics 8 (2010): paragraph 5. https://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=585

- A. Fraser, “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique” ARTFORUM 44, no. 1 (2005): 278–83.

- Jennifer Snider, Art Administration as Performative Practice, 10 July 2019, (OCAD University Thesis, 2015), 5. http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/295/1/Snider_Jennifer_2015_MA_CADN_THESIS.pdf.

- Simon Sheikh, “Notes on Institutional Critique,” in Art and Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critique (London: May Fly Books, 2009), 29–32.

- Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions” October 55 (1990): 105–43.

- Gary Genosko, Félix Guattari: A Critical Introduction, Modern European Thinkers (London; Pluto Press; 2009), 51.

- Joshua Alan Ramey, The Hermetic Deleuze: Philosophy and Spiritual Ordeal (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 150.

- Gilles Deleuze, Two Regimes of Madness: Texts and Interviews 1975-1995 (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2006), 382.

- Susan Kelly, “The Transversal and the Invisible,” Transversal Web Journal, European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies 2005, 10 July 2019, http://eipcp.net/transversal/0303/kelly/en/print.html.

- Jennifer Snider, “Art Administration as Performative Practice” (OCAD University, 2015), 23.

- Robin Laurence, “Fabled Territories Raises Complex Issues,” Georgia Straight, November 29-December 5 (1991): 31.

- Paul Wong, Yellow Peril Reconsidered: Photo, Film, Video (Vancouver, B.C.: On the Cutting Edge Publications Society, 1990).

- Zara Suleman, “Race and Representation: Picking at the Gallery’s Locks,” Kinesis Dec/Jan (1992): 22.

- Ann Rosenberg, “Racism Charges against Gallery Aired,” The Vancouver Sun, December 7, 1991.

- Karlyn Koh, “Local Colour Challenges VAG,” Ubyssey 74, no. 27 (1994): 3–5.

- Zainub Verjee and Sher-azad Jamal, “Artists Coalition for Local Colour, Press Release” (Coalition for Local Colour, November 19, 1991).

- Sher-Azad Jamal, “Where Outreach Meets Outrage – Local Colour and The Vancouver Art Gallery,” Front, no. Jan/Feb (1992): 19–21.

- Ann Rosenberg, “Racism Charges against Gallery Aired,” The Vancouver Sun, December 7, 1991.

- Fatima Khadija, “Systemic Racism – In Whose Interests? The Artist’s Coalition vs. the Vancouver Art Gallery,” South Asian Women’s Network, 1991.

- “Ismaili Imamat,” “New Canadian Film Records the Work of Zainub Verjee,” 2 July 2019, https://ismailimail.blog/2019/07/02/new-canadian-film-records-the-work-of-zainub-verjee/.

- Monika Gagnon, Other Conundrums: Race, Culture, and Canadian Art, (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2000).

- Adam Bryx and Gary Genosko, “Transversality,” 2 July 2019, Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias, http://deleuze.enacademic.com/177/transversality.

- “Ismaili Imamat,” “New Canadian Film Records the Work of Zainub Verjee,” 2 July 2019, https://ismailimail.blog/2019/07/02/new-canadian-film-records-the-work-of-zainub-verjee/

- Monika Gagnon, “In Visible Colours: Women in Focus,” C Magazine, no. 25 (1990): 73.

- “History” SAVAC (blog), 12 July 2019, https://www.savac.net/about/history/

- Zainub Verjee, “Retro-Desh Program Brochure” (Desh Pradesh, 1998).

- Zainub Verjee, Media Mirage- Zero Hour in the Holy Land, 3rd Edition IMAGES Festival (Toronto, 1991), 15.

- “The Gulf Crisis TV Project (1990-1991), 10 July 2019, https://vimeo.com/showcase/4093685.

- Barbie Zelizer, “CNN, the Gulf War, and Journalistic Practice,” Journal of Communication 42, no. 1 (March 1, 1992): 66–81.

- Karen Tisch, “Note on the Critical Frameworks Panel,” C Magazine, no. Fall (1991): 67.

- United Nations, “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007),” (United Nations, 2008).

- Teri Hansen, “Reconciliation Is the New Assimilation: New NAIPC Co-Chair,” 14 July 2019, IndianCountryToday.com, https://newsmaven.io/indiancountrytoday/archive/reconciliation-is-the-new-assimilation-new-naipc-co-chair-CKt1BryEUUCnO_9cPsvpwA/.

- Zainub Verjee, “Âhasiw Is Canada – Zainub Verjee Ghostkeeper,” 14 July 2019, grunt gallery, https://ghostkeeper.gruntarchives.org/essay-ahasiw-is-canada-zainub-verjee.html.

- Notes from author’s informal interviews with Zainub Verjee, 2018.

- Suzanne Grano, ed., The First Asia-Pacific Contemporary Art Triennial Brisbane Australia 1993, (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, Queensland Cultural Centre South Brisbane, 1993).

- Eunju Choi and Subir Choudhury, The 1st Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 1999: The Commemorative Exhibition of the Inauguration of Fukuoka Asian Art Museum (Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan, 1999).

- Niranjan Rajah, “WHO Do You Represent?” in Present Encounters Papers from the Conference, The Second Asia Pacific of Contemporary Art Triennial, ed. Caroline Turner and Rhana Devenport (The Second Asia Pacific of Contemporary Art Triennial, Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Art Gallery, 1996).

- Niranjan Rajah, “Towards a Southeast Asian Paradigm: From Distinct National Modernisms to an Integrated Regional Arena for Art,” 36 Ideas from Asia: Contemporary South-East Asian Art. (Singapore: ASEAN COCI [Singapore Art Museum], 2002), 26–37.

- Apinan Poshyananda, Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions, Tensions (New York: Asia Society Galleries, 1996).

- Notes from author’s informal interviews with Zainub Verjee, 2018.

- Arjun Appadurai, “The Production of Locality,” Counterworks: Managing the Diversity of Knowledge, edited by R. Fardon, 204–55. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Western Front, “Performance by Dadang Christanto,” 10 July 2019, https://front.bc.ca/events/performance-by-dadang-christanto/.

- Eric Toussaint, “The World Bank and the IMF in Indonesia: An Emblematic Interference” 10 July 2019, http://www.cadtm.org/The-World-Bank-and-the-IMF-in-Indonesia-an-emblematic-interference.

- University of Michigan. East Asian Program., Newsletter, East Asian Art & Archaeology, no. 44–45 (1980).

- “North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),” Office of the United States Trade Representative, 14 July 2019, https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/north-american-free-trade-agreement-nafta.

- Sabine Schorlemer and Peter-Tobias Stoll, The UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions: Explanatory Notes (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012), 311.

- Garry Neil. “Response of the UNESCO Convention to the cultural challenges of economic globalisation” International Network for Cultural Diversity. http://www.incd.net (2005).

- UNESCO, “Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (Paris: UNESCO, 2005), http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001429/142919e.pdf.

- Notes from author’s informal interviews with Zainub Verjee, 2018.

- Helen Milner, “Globalisation, Populism and the Decline of the Welfare State” IISS, 10 July 2019, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/survival-blog/2019/02/globalisation-populism-and-the-decline-of-the-welfare-state.

- Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1991).

- Robert Bellah, “Finding the Church: Post-Traditional Discipleship” Christian Century 33, no. 1060–1964 (1990): 107.

- the.Ismaili, “Ismaili Imamat,” July 11, 2019, https://the.ismaili/imamat.

- Merchant Abdulmalik, “Perspectives on the International Art Gallery at the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee Celebrations in Lisbon” Barakah (blog), August 13, 2018, https://barakah.com/2018/08/13/perspectives-on-the-international-art-gallery-at-the-aga-khans-diamond-jubilee-celebrations-in-lisbon/.

- Kristina Lee Podesva, At a Critical Juncture: On Ken Lum’s Entertainment for Surrey (Surrey Art Gallery, 2017).

- Roopesh Sitharan, ed., Relocations Electronic Art of Hasnul Jamal Saidon & Niranjan Rajah (Minden: Muzium & Galeri Tuanku Fauziah, Universiti Sains, Malaysia, 2008).

- Ken Lum, Ken Lum, (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2011).

- Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1990).