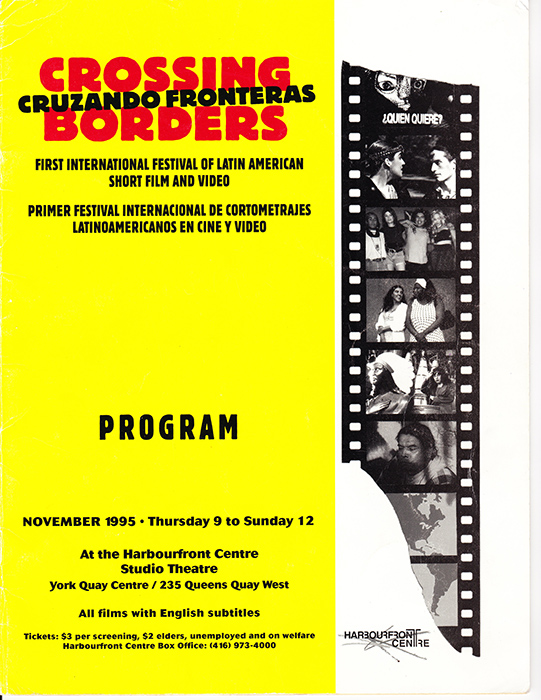

Program for Cruzando Fronteras / Crossing Borders (1995). Courtesy of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival.

Maria Alejandrina Coates

A PEOPLE’S STORY OF THE ALUCINE LATIN FILM AND MEDIA ARTS FESTIVAL

A HISTORY OF LATIN AMERICAN MEDIA ARTS ORGANIZATIONS is one deeply intertwined with world politics, Canadian immigration policy, art history, local infrastructure for the arts, and more prominently, the vastly overlooked lives and circumstances of the people who organize, produce and carry the work forward year after year in often precarious and informal conditions of employment.

Tracing the undercurrent of those relationships helps us understand the formation of movements and organizations that address the complexities and contradictions of rep- resentation for minorities in a globally mediated world. In this essay, I will profile the voices of the previous and current Artistic and Executive Directors of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival, as a glimpse into the lived experiences that situate contemporary curatorial platforms and artistic practices of Toronto’s Latin American community. This essay is not meant to be a comprehensive overview of aluCine’s history and the history of the people that were a part of it. Rather it is a fragment of a larger narrative that seeks to trace the perspectives of a number of Latin American cultural catalysts and their platforms in Toronto. This essay is based on a set of interviews with Jorge Lozano, Sinara Rozo Perdomo, and Juana Awad. My aim is to examine the missions, milestones and impact of aluCine’s platform in today’s cultural mediascape, in order to better ground myself and the next generation of culturally diverse artists, curators, and cultural workers to continue to question existing structures of representation and make visible the normalized and institutionalized precarity of arts labour in increasingly digitized platforms.

Momentum for what is now known as aluCine was driven from a local movement in which minority artists and arts organizations organized themselves to call attention to the lack of representation and funding for artists of colour, immigrants, and women in Toronto. In this context, acclaimed Chilean artist and filmmaker, María Teresa Larraín, had been working with a like-minded group of artists and filmmakers to address the failures of the dominant art councils and organizations in being inclusive of artists of colour. Jorge Lozano, then a recent graduate from OCAD met Larraín after she completed a film that addressed the theme of domestic violence, called Amor Amargo. When Jorge did some camera work for her, the two became friends and she invited him to participate in her working group. He slowly became more involved, attending the conference called Shooting the System that took place in 1989.1 This conference was organized by the organization Full Screen, with the participation of figures like Premika Ratman, Richard Fung, and Cameron Bailey—who, says Lozano, were being either absorbed into, or left out of the mainstreams of representation through a lack of funding and visibility.2 The conference included roundtables which called on Arts Councils to address systemic issues of representation, which included little to no participation of minority artists as jurors or in leadership positions within their infrastructure. According to Lozano, the conversations opened up during this conference gave way to a shift in consciousness by councils to represent and fund diverse artists, resulting in a movement of inclusion and empowerment for artists of colour.3

These conversations spoke deeply to Lozano, who grew up in Cali, Colombia, and immigrated to Canada after befriending a Canadian while attending university in Colombia in 1970, where he was experimenting with poetry and writing within revolutionary student politics. His friend had invited him to come and live in the Toronto Islands. Back then, the immigration system was less formal, and a letter of invitation was all that was needed to enter the country. At the islands, Lozano was immersed in a culture of cinema, photography and revolution. When he later attended OCAD in the 1980’s, Lozano already had a formation in experimental photography and video, a rebellious attitude and a firm anti-colonial stance informing his practice. His intentions were not to assimilate, but to strengthen his alterity and defend different ways of thinking and being, to create a process of identity that continually negotiates between what one was, and what one is in a different culture and foreign place. Part of that process, he says, is the daily struggle with bias that breaks the flow of mundane tasks and everyday interactions, in what he calls “crashing against a wall.”4

The energy mobilized by the Shooting the System conference gave space for a group, including Jorge Lozano, Irma Iranzo Berrocal, Ricardo Acosta and Ramiro Puerta to put together the first national encounter of Latin American film and video makers, under the name of Cruzando Fronteras (Crossing Borders). It all came about when he heard from his friend, Jeaneth Lara, that there was a large presence of Latin@ filmmakers living in Montreal who had attended a different event in Banff, organized by the Independent Media Arts Alliance (IMAA/AAMI). “I felt that we were not alone. I called Ramiro and Ricardo. Ramiro had just started making his first film shot in Havana. I helped him to sync the sound and with some editing, and Ricardo had just come back from Holland to edit a film Three Sevens (1993) that I had made with Alejandro Roncería. I proposed them to organize a conference with a screening included. We asked Jeanneth Lara to work on the project and I coordinated and directed the event.”5

Jorge Lozano was a strong instigator for the festival as a space for the visibility of alternative and experimental works by Latin American artists, both in Canada and abroad. The Cruzando Fronteras Conference took place in November 1993 and included thirty-nine artists who showcased thirty independently produced works.6 The conference enabled encounters between Latin American/Latin Canadian artists and filled in an important void for the presentation of work by Latin@ artists. At the same time, the group made up of Maria Teresa Larraín, Jorge Lozano, and Ramiro Puerta registered a Not-For-Profit organization to act as a platform for the showcasing of Latin American experimental Film and Media. It was named Corrientes del Sur / Southern Currents, as a direct contraposition to Northern Visions, the not-for-profit under which the established Images Festival operates. This positioning was part of a curatorial agenda that intentionally eschewed an assimilation into the existing cultural paradigms of local art practices, “I was always angry at them because they never showed Latin works or just a few. The idea was to create a bridge between us here and filmmakers in the south of America,” says Lozano.7 The original Board of Directors was composed of Ricardo Acosta, Irma Iranzo, Jorge Manzano, Beatriz Pizano, and Ramiro Puerta.8

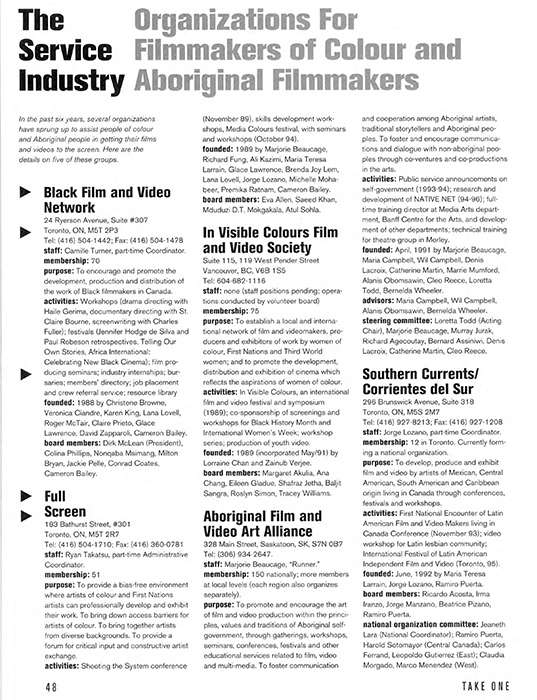

Take One, film and Television in Canada 5 (Summer 1994): 48

Meanwhile in Colombia, in 1994, Sinara Rozo Perdomo, aluCine’s current Executive Director, was 22 years old and a big cinema buff. After graduating with a degree in Social Communication she was working in the industry to produce commercials with Colombian talent. On the side she produced a few of her own films, and actively participated in the local film circuits. It was during the Caracas International Film Festival in 1994 where her and Jorge’s paths crossed for the first time. While she was there attending the festival, he was there screening one of his pieces. They quickly became friends through their common interests in cinema, and later that year, they would find each other again at a film festival in Bogotá. Their relationship soon turned romantic despite the long distance between them.9

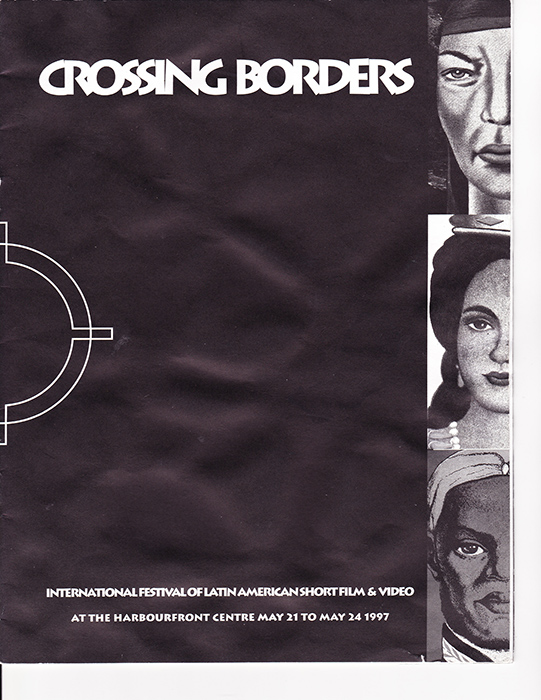

In 1995, while Rozo was in the United States, Lozano invited her to spend the summer in Toronto. She arrived on June 15th of that year on a visiting visa and spent the subsequent months working with Jorge to make manifest the idea of a Latin American film festival proposed by Lozano, Puerta, and Acosta two years earlier. During those five months, Lozano and Rozo (and Acosta) volunteered their time and managed to finance the festival with their own unpaid work and in-kind donations. The Harbourfront Centre came on as a partner to host the event, while the opening and closing reception parties were held at Bar Tacones, an LGBTQ Bar in the area.10 They were supported with other volunteers like Professor Susan Martin and Ilana Gutman who helped with promotions and poster distribution. With their collective efforts, the first Cruzando Fronteras Festival took place over the last weekend of November in 1995, with an overwhelmingly supportive response by the community.11 There was a large turnout for the features, as well as the presence of influential guests from New York—like director Rose Troche’s screening of Go Fish (1994), which had been released earlier that year at the Sundance Film Festival. This energy and success motivated them to repeat the festival every few years, with subsequent iterations in 1997, 1999, 2002, and yearly after that—yet not without a few obstacles.

In 1997, after being in the country for two years, Rozo received a letter from the government saying that she had overstayed her visa. In dire straits, the options were two: either pack up and leave, or get married and stay. Since she and Lozano were already living and working together, they decided the logical step was to get married, thus solidifying her residency in the country as a landed immigrant.12 The honeymoon period, however, was over almost as soon as it began. The work of the festival never left the house, and her duties encompassed all sorts of responsibilities, including those of administrator, designer, programmer, and marketer, while working night shifts at a bar. At first, they tried to work from an office, but “it was tiny and asphyxiating,” says Rozo. Eventually, they moved the office to their living room, and from there the festival operated for many years. “For me,” she says “it was very difficult to live together and work together. It is hard when you wake up together and go to bed together, and are stuck together all day. I had never had a relationship like that and I had never lived and worked with someone. At the same time, it was very productive, very easy. For me it was normal, that was the life we wanted and I liked what I was doing, I was happy with everything, but there were also a lot of arguments about aesthetics, about processes”13. As a relative newcomer to Canada, it was Lozano who knew the local industry the best. Though they watched all the material and programmed the festival together, it was him who made almost all the final decisions, and who executed the role of Artistic Director. “What Jorge said, was what was done,” says Rozo, “He was stubborn and insistent and I didn’t want to fight, I didn’t want to argue. There were personal challenges, but we always put the festival first, they were very interesting and of very good quality”14.

Program Cover Page from Cruzando Fronteras / Crossing Borders (1997). Courtesy of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival.

Their marriage came to an amicable end in 1999, though they continued to work together for the festival for a few more years after that. In 2000, they began to qualify for a number of project grants and were finally able to see some compensation for their work. “My first cheque was for three hundred dollars, for three years of work,”15 recalls Rozo. Similarly, Lozano remembers, “all that we really needed was money to make it better and to be able to pay ourselves a decent salary that we never had. I spent ten or more years in the festival and many times I spent my own money. Out of my own money I used to cook for the people working in the festival and I left the festival without anything, no protection of any kind. It was the same for all of us.”16 In 2002 they received a three year, capacity building grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, which coincided with the same year Rozo stepped down to go on maternity leave, also citing her personal unease with the Festival’s heavy focus on experimental works, and the decisions to feature less of documentaries and fiction as part of the program.17 Since they were looking for a replacement for Rozo’s role in the organization, they used that funding to hire Juana Awad, now an Independent New Media Arts Curator currently based in Berlin.

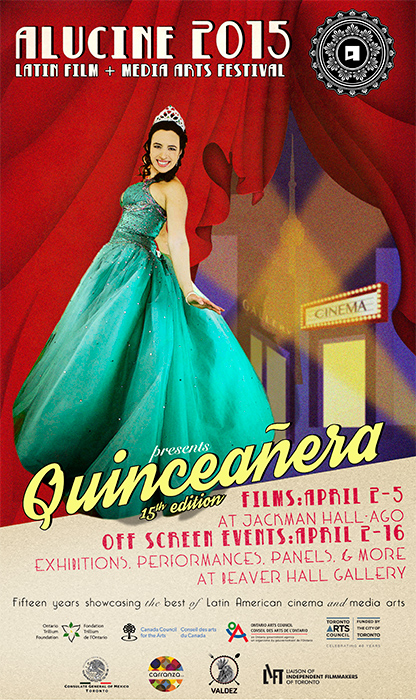

Catalogue cover page for aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival, 2015. Courtesy of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival.

Juana Awad arrived in Canada in 1998 at the age of 19, as a refugee from Colombia. Prior to obtaining a degree in Drama and Semiotics at the University of Toronto, “I began looking for work and met Jorge and Sinara while as a singer for the urban Colombian music band ‘Palenque Orquestra’” she says.18 Rozo knew of Awad through the art world, and both her and Lozano interviewed her for the job. They thought she was a responsible, dedicated, and well-prepared person for the position, and so, Awad joined their team as Festival Coordinator. She received a small salary for her services and was able to complement it with a stipend from an employment subsidy program.19

After Rozo stepped down, Awad began to take on more responsibilities and manage all aspects of the festival. In this capacity, Awad secured funding from the Department of Canadian Heritage as well as the Trillium Foundation, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Toronto Arts Council, increasing the operating budget three- fold. “In three years,” she says “aluCine was transformed from a two-person operation, to a larger organization that had achieved a growth of 300% percent. It went from being a festival focused narrowly on film, to one that was multidisciplinary, and aimed to include the Latin American artistic community at large.”20 With Awad’s leadership, the festival established itself and increased its capacity to involve a team of collaborators, including curator Guillermina Buzio, artist Alexandra Gelis, Lina Rodriguez, Diana Cadavid, Hugo Ares, and Jessica Morales, who while working with aluCine elevated the festival as a platform of international scope at the same time that the team developed their own work and gained experience in the industry. In Lozano’s words “aluCine was a collective endeavour where most people came with great energy and dedication. Most people came to aluCine as volunteers. Diana Cadavid called me once to volunteer and ended up helping me to organize the programming that at the time we were doing with little pieces of paper on the floor …. We were all directors or programmers, at the time that Juana was working there, Guillermina Buzio was doing programming and organizing the outreach of the festival as well, Hugo Ares was doing programming and doing finances and other things. Later Lina Rodriguez was doing publicity. Alexandra Gelis later started doing programming. Guillermina was moving aluCine in Buenos Aires, Hugo was doing the same. We were kind of a family, and our mutual support helped us to grow as artists and organizers …. We all wore many hats to resist complacency and assimilation …. There were conflicts like in any organization, but we were together.”21

Yet the lack of funds and informal setting were also something to be reckoned with. Approximately 200 shorts were presented annually during this period, along with parallel programming in the visual arts. Moreover, with funds secured from the Department of Canadian Heritage, Lozano and Awad co-developed alucinArte, a platform whose aim was to present to a Toronto audience the innovative and contemporary works by Latin@ artists in various mediums.

During Awad’s tenure she organized five large-scale instances of the festival and two large-scale editions of alucinArte, “where I was often working sixteen-hour days and having to sleep in the office many times.”22 Her feeling, says Awad, was that “this practice constituted a type of activism, and that aluCine’s role was an important platform for increasing the visibility of artists and communities of colour, despite the precarious economic conditions and difficult working relationships within the organization. I grew up in a community of human rights and environmental workers, and it was only natural to extend this strive for justice to my field, the arts.”23 Throughout those years with aluCine she had absolute conviction in the work she was doing as a curator and arts administrator, and at the same time was able to develop her own artistic practice moving between theatre and video art. She grew within the organization and attained the position of Co-Director. But “Looking back,” says Awad, “that type of work was unsustainable; there was a great imbalance of power between me and Jorge, regardless of how much I contributed intellectually and organizationally, and this was amplified by the fact that the Board of Directors, while being all very nice people, did not really oversee or participate very much.”24 Though they were co-directors, Lozano was 30 years her elder and retained all final executive-decision making capacities, including signing authority over the accounts and the control of the work space (as the festival office was still in his home).25

By 2005, the festival had become quite large, providing a general, loosely focused, and diverse overview of Latin American and Latin Canadian work being produced, while its audience had become more limited. Despite the desire and intention to involve and include the general Latin@ community in Toronto, there were several factors affecting its reach. “Competition with other film festivals was a big one, not only for us but for the other festivals in the city as well. Toronto had in average one film festival every five days,” says Awad, “as was the fact that we were caught in a complicated catch 22, presenting experimental works that the mainstream Latin audience did not watch, and Latin works, which the artist community did not pay much attention to.”26 At the same time, other artists, including those working under the umbrellas of e-fagia and LACAP, were working in parallel and beginning to institutionalize themselves.27 Crosspollination between these three organizations was constant, as many times members of one, collaborated with or were presented by another.

During that year, while involved in discussions and advocacy with IMAA/AAMI regarding the formation of MANO/RAMO, Awad decided to step down from aluCine, as the internal relationships had become untenable. She worked for the Toronto International Film Festival and moved to England to pursue a Master’s Degree at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, UK. To this day she says, “I am very proud of the curatorial and organizational work I did, the grants and funding I secured, and the visibility I achieved for the Festival within the Canadian artistic ecosystem.”28 She is also happy that the organization was able to survive both her and Lozano’s tenure, and feels the Festival maintains its relevance as a form of cultural activism. “Despite the lack of a cohesive theoretical framework at the time, the Festival operated to make visible the work of Latin American and Latin Canadian artists among the Canadian artistic community and at large, showing important, radical artistic and emancipatory positions; an act that places it within a decolonial practice, regardless of whether or not this was expressed in those terms at the time.”29

Without Awad, the festival continued with business as usual, and in 2008 Sinara Rozo returned to the organization with a Master’s degree in Film and Cinema from York University. When she did, she found aluCine to be operating with overworked personnel, a lack of funding, and minimal outreach and development strategies to include a complex and diverse audience. She sought to implement several changes, beginning with diversifying the work being showcased, which at the time was mostly experimental. “I was already coming in with a different vision. It’s because when you go to University, you learn so many things and you realize that we were doing things wrongly, with methods and habits that were not healthy for the organization. So, then I come in with lots of ideas, with lots of energy to do things differently, more effectively, but there was a lot of resistance to change […] and that was a year of big confrontations,”30 describes Rozo of the time. After this difficult year, in 2009, Lozano stepped down as co-director of the Festival to pursue other projects and renew his practice in different areas, leaving Rozo in charge, who immediately began to restructure the organization.

With Diana Cadavid as Programmer, the Festival began to include more works of different genres; including documentary, fiction, drama, feature films, independent films, as well as a program targeted specifically for children, called Shorts for Shorties. At the governance level, Rozo was able to recruit a new working Board, and received a Compass grant to hire consultant Judy Wolfe to train with them on organizational development.31 This new Board gave Rozo the support she needed for a renewed vision and sustained growth of the Festival. Within the next few years, the Board revised and updated the Bylaws, created a manual for human resources, and also registered the Not-for-Profit as a Charitable Organization with the Canada Revenue Agency, thus enabling Rozo to diversify fundraising efforts. They also give her a mandate, and make collaborative decisions that she then executes with her team on the ground32. “Now everything is more formal, when you start to grow, you need a stronger structure, and so it was necessary to get a new Board in place,” she says, “but we still have a long road to walk in terms of audience development. Though we are recognized in the industry, I am aware that not all of the hispanic or latin@ community knows about us; we have to invest more in that but don’t have a lot of budget for publicity.”33 The biggest challenge and the biggest aspiration of the organization is to “be able to have long-term financial security through private or corporate sponsorships, but we haven’t been able to do that yet …. It is very hard to get the latin@ community to donate, they invest in ‘fútbol’ and in ‘rumba’, but not in culture …. It would be a relief to be able to have year-round staff that could focus only on sponsorship and development …. I still have to do things for the greater part of the year on my own: write grants, programming, coordination, training, training, training…”34

Though unstable funding and a high turnover rate in staff continue to challenge the administration; and despite the growing pains of an organization whose mandate includes the on-screen representation of diverse people within a whole continent—and its diaspora— the festival not just showcases important and relevant work, but acts as a incubator for Latin American artists, cultural workers and students to apply their skills and develop their practice. Lozano recalls that back in his era “we created a program called ‘aluCine in Bytes’ to show the work that we all did because we refused to show ourselves only as administrators or programmers, we were also filmmakers and wanted to be on the same ground with the filmmakers that we were representing.”35 The pride of the organization lies in giving space to youth and emerging voices to grow their talent. “My favourite memories are the workshops we did with latin@ youth who are dropping out of school […] when they have access to an alternative space along with the tools to work creatively, you can really see them shine” says Rozo.36 Similarly, Lozano echoes his appreciation of “all the Latin youth from Jane and Finch and other excluded areas of Toronto and in Cali, Colombia who created fabulous strong and challenging works made within the aluCine context.”37 Though in practice the festival has changed significantly form what it began as, its essence as a platform for developing Latin American talent stays true. This has included me personally, when in 2015, I participated with aluCine in a curatorial residency funded by the Ontario Arts Council.

My experience gave me a glimpse into the inner workings of a cultural organization that is in constant movement, not just in navigating the give and take of collaborative working methods, interpersonal conflict, or featured content, but in the spaces and platforms that are chosen to occupy and display work. As a space for film and media arts, aluCine has expanded beyond the projection room to include multimedia exhibitions, performances, sound, and good old-fashioned conversation. And I think it is important to talk about aluCine in the context of our current climate, where the cultural differences between Anglo and Latin America are being magnified by the development of information technologies, and particularly the role of film, video, computers, the internet, and social media in mass communications. In the last fifteen years we have seen the rise and impact of digital interfaces and global networks as powerful tools being utilized in very different ways. On one hand they have functioned as grassroots tools for self-representation and empowerment, while on the other, they are tools in a campaign for surveillance and misinformation with the potential to compromise our subjectivities. While aluCine has supported the former, it is important to move organizations and institutions to support not just the work, but the livelihood of artists, producers, and workers in the cultural industries through adequate compensation as well as with processes that are radical, equitable, and safe; protecting workers in an increasingly prevalent digital and ‘gig’ economy that distances labour from what we see on the screen.

What we can now ask, based on aluCine’s origin stories, is how to negotiate the radical potential of informal working environments as subversive methods for producing creative work, with the precarious working conditions that naturally stem from those environments, in what is already precarious labour for immigrants and people of colour in Canada, especially for women. How can film and media arts organizations play a role that encompasses safe spaces for alterity both on and off screen, while still accessing funds that support culture and creativity? Our work towards answering those questions is far from over.

NOTES

- 1 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.

- 2 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. August 10, 2018.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-Director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.

- 6 “History,” aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts website, https://www.alucinefestival.com/our-vision/ (Accessed on November 12, 2018).

- 7 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-Director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.

- 8 “Organizations for Filmmakers of Colour and Aboriginal Filmmakers,” Take One: Film & Television in Canada’s, http://takeone.athabascau.ca/index.php/takeone/article/viewFile/108/102 (Accessed on December 13, 2018).

- 9 Sinara Rozo, (Executive Director, aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. April 26, 2018 and December 7, 2018

- 10 Ibid.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Ibid.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14 Ibid.

- 15 Ibid.

- 16 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.

- 17 Sinara Rozo, (Executive Director, aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 7, 2018.

- 18 Awad, Juana (Curator, Previous Co-Director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. August 24, 2018.

- 19 Ibid.

- 20 Ibid.

- 21 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.

- 22 Awad, Juana (Curator, Previous Co-Director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. August 24, 2018.

- 23 Ibid.

- 24 Ibid.

- 25 Ibid.

- 26 Ibid.

- 27 Ibid.

- 28 Ibid.

- 29 Ibid.

- 30 Sinara Rozo, (Executive Director, aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 7, 2018.

- 31 Ibid.

- 31 Ibid.

- 33 Ibid.

- 34 Ibid.

- 35 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.

- 36 Sinara Rozo, (Executive Director, aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 7, 2018.

- 37 Jorge Lozano, (Artist, Previous Co-director of aluCine Latin Film and Media Arts Festival). “Interview with Maria Alejandrina Coates”. December 11, 2018.