Dana Claxton, I Want to Know Why (1994). Single-channel video with audio, 6:20 minutes. Courtesy of Video Out Distribution/VIVO Media Arts.

Grant Arnold

THE ART OF DANA CLAXTON: A PROLOGUE

The indian is a simulation, the absence of natives; the indian transposes the real, and simulation of the real has no referent, memories or native stories. The postindian must waver over the aesthetic ruins of indian simulations.1

OVER THE PAST THREE DECADES Dana Claxton has become widely known for an expansive multidisciplinary approach to artmaking that encompasses film, video, photography, and performance and is informed by a remarkable family history and an extraordinarily cosmopolitan range of lived experience. More specifically, her work combines contemporary technologies and aesthetic strategies drawn from disparate idioms—from 1980s music videos to post-conceptual photography—with references to Indigenous cultures, particularly her own Lakota culture, to address the ongoing impact of colonialism on contemporary life while eloquently articulating Indigenous histories, world views and spirituality. To put it another way, her efforts to make space for the Indigenous subject in the gallery/museum system could be described as “fringing the cube”—an expression that draws upon the practical and metaphysical functions of fringe for the First Peoples of the Great Plains and the performative role Claxton has taken on to create that space.

Claxton’s career as an artist began at a critical point in the struggle of First Nations for recognition of their claims to sovereignty by the Canadian state, a struggle in which the Oka crisis of 1990 remains as one of the most prominent episodes. Precipitated by plans to build a golf course on a traditional Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) burial ground near the Québec town of Oka, a peaceful blockade of the site became a 78-day armed standoff in which gunfire was exchanged, a Sûreté du Québec officer was killed and the province requisitioned assistance from the Canadian military. The crisis received extensive media coverage, which, although it tended to reflect a non-Indigenous perspective, sharply heightened awareness of the intense and deep divisions that separated First Nations and the non-native public, especially in regard to questions of history and the ownership of land.

The Oka standoff corresponded roughly with a moment when contemporary Indigenous artists who were directly addressing the effects of colonialism—such as Joanne Cardinal- Schubert, Robert Houle, Carl Beam and Jane Ash-Poitras—were making inroads into the country’s predominantly Euro-Canadian art gallery/museum system. The crisis resonated intensely within the Canadian art world over the following years. It undoubtedly framed the organization of Indigena and Land, Spirit, Power, exhibitions mounted at the Canadian Museum of Civilization and the National Gallery of Canada respectively in 1992 to “decelebrate” the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in America. The programming that accompanied Land, Spirit, Power, for instance, included film footage shot during the crisis by the Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin, which would later be used in her feature-length documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993). Commenting on the experience of watching footage “of nervous Canadian soldiers on the verge of hysteria because some eggs had been thrown at a tank, spliced with a scene of a badly beaten Mohawk,” Scott Watson later wrote that, “The film reminded us all of how close the Oka crisis came to utter disaster. It reminded us all that the veneer of civilization is very thin, and that Canadians are not exempt from the racism they love to accuse others of.”2

The Oka crisis was galvanizing for Claxton. As she later put it, “I realized there was much work to be done. Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities were not communicating with each other. I asked myself: how could I facilitate this huge gap, in a meaningful way.”3 This led Claxton to make her first film, Grant Her Restitution (1991), with a secondhand Super 8mm film camera and curate two exhibitions of work by Indigenous artists— NeoNativists and First Ladies—for Vancouver’s artist-run Pitt Gallery. An early indication of Claxton’s longstanding interest in honouring the role of women in Indigenous cultures, First Ladies focused specifically on work by Indigenous women and included a star quilt by Kelly White and wigwas (birch bark bitings) by Angelique Levac, work that usually would have been seen as craft in an art museum context.

For Claxton the art world held out the potential to reconfigure the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the dominant Euro-Canadian culture on at least two accounts. On one hand, recognition of the significance of work by Indigenous artists offered the possibility for a fundamental shift in the terms through which Aboriginal culture has been perceived; as she would later note,

the lens through which Western society viewed Aboriginal people resulted in the devaluation of Aboriginal art as a lower cultural form; the Aboriginal, it was believed, could never produce great art and therefore this lens was a critical part of the colonial rhetoric. The very idea that an Aboriginal could produce great art would erode the very underpinnings by which European colonizers and their descendants justified their destructive aims against Aboriginal civilizations.4

Secondly, while the space of the gallery/museum is far from neutral and has often replicated conventional relationships between dominant and marginalized cultures, it is also a “site where the most radical and polemic critiques of Canadian society have taken place.” And, although perhaps only through pressure from Indigenous artists, it was a space in which “the art community has helped lead the decolonization process ….”5

While Fringing the Cube might claim to survey Claxton’s career as an artist, it is important to note that the artworks represented in this publication and the exhibition it accompanies are only one aspect of a broader project of reclaiming and redefining Indigenous culture she has taken on. Over the past 30 years she has scripted plays, produced and directed children’s programs and documentary films for broadcast television, organized conferences, edited anthologies, and written extensively on Indigenous art. She was a founding member

Dana Claxton, I Want to Know Why (1994). Single-channel video with audio, 6:20 minutes. Courtesy of Video Out Distribution/VIVO Media Arts.

of the board of directors of the Indigenous Media Arts Group and IASPA (Independent Aboriginal Screen Producers Association). She has curated exhibitions for traditional gallery spaces and the Internet, participated in the Sitting Bull Sundance at Standing Rock, South Dakota, and actively supported the Standing Rock Lakota and Dakota in their opposition to the Dakota Access oil pipeline. She has taught in the School of Journalism at the University of Regina, the Department of Women’s Studies at Simon Fraser University, the Emily Carr University of Art + Design, and the Department of Art History, Visual Art & Theory at the University of British Columbia, where she currently chairs the department. Community is central to her practice; her recent work the Sioux Project—Tatanka Oyate, which was exhibited at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina in 2017, grew out of a number of workshops with Sioux youth from the Standing Buffalo and White Cap First Nations and is presented in a video installation based on the form of a sundance circle. Her work has been included in film festivals in Canada and the United States and her artwork has been presented in prestigious art world venues such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and in spaces with a more direct connection to plains Indigenous cultures, such as the Wanuskewin Heritage Park in Saskatoon.

Claxton has employed a diverse set of strategies in her efforts to reclaim history and assert an Indigenous presence within it. Much of her early work is characterized by the disruption of imagery that might appear benignly familiar to a non-Indigenous audience through the deployment of specific tropes, references and formal devices. I Want to Know Why (1994)—a forcefully polemical work that dialogically addresses the events that brought Claxton’s ancestors to Canada—deliberately mimics the look of an archival film in its gritty black and white character while its fast paced editing and use of a multiple frames within a frame format recalls the music videos that were a common sight in nightclubs and bars at the time the work was made. The almost banal images of the once ubiquitous Indian TV test pattern, drive-by views of the Statue of Liberty and architectural details that feature stereotypical representations of Native people are accompanied by a harrowing voice over, in which Claxton demands to know why her great-grandmother had to walk, starving, to Canada and what led to the early death of her grandmother and mother. The only Indigenous presence in the work, Claxton’s increasingly assertive voice contrasts sharply with the near-universal absence of an Indigenous subject position within popular culture, an absence signaled in the relentless repetition of clichéd images of Indian-ness and their juxtaposition with images of a colossal tourist attraction. Through the video’s montage effects, the trauma of the history Claxton recounts and the rage that marks its telling, the Statue of Liberty is shifted from an emblem of the freedom and prosperity (however mythical these might be) the republic offered the dispossessed that arrived on its shores into a hollowed out marker of the effacement of Indigenous identity and the loss of freedom and prosperity that was inflicted in the disasters that waves of European immigration brought to the inhabitants they displaced.

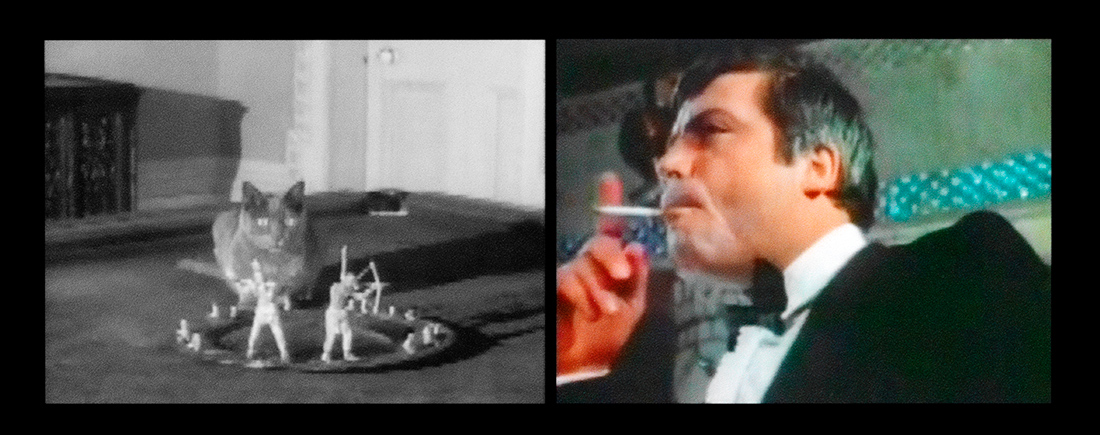

In contrast to I Want to Know Why, the single-channel video 10 (2003) and the photographs that comprise the AIM (2010) project are both made up of appropriated imagery. Drawn from three different feature films based on Agatha Christie’s Ten Little Indians,6 an immensely popular detective novel written in the late 1930s that took its title and narrative structure from a popular nursery rhyme, Claxton’s 10 is comprised of precisely chosen jump cuts presented as side by side images in a single frame. The genteelly ominous atmosphere of Christie’s story, one of the principal templates for the modern detective novel, along with costumes, mannerisms and camera work that are clearly associated with particular eras in fashion and cinema are immediately familiar in the excerpts Claxton has assembled. As the video progresses though, any pleasure that might be associated with familiarity on the part of a non-Indigenous viewer is incrementally undercut through the repetition of the nursery rhyme’s lyrics and the concurrent recognition of the connotations carried by the enduring popularity of a children’s song that playfully describes the death of “little injuns” and the implications of its use as a conceit for plot development in popular entertainment.

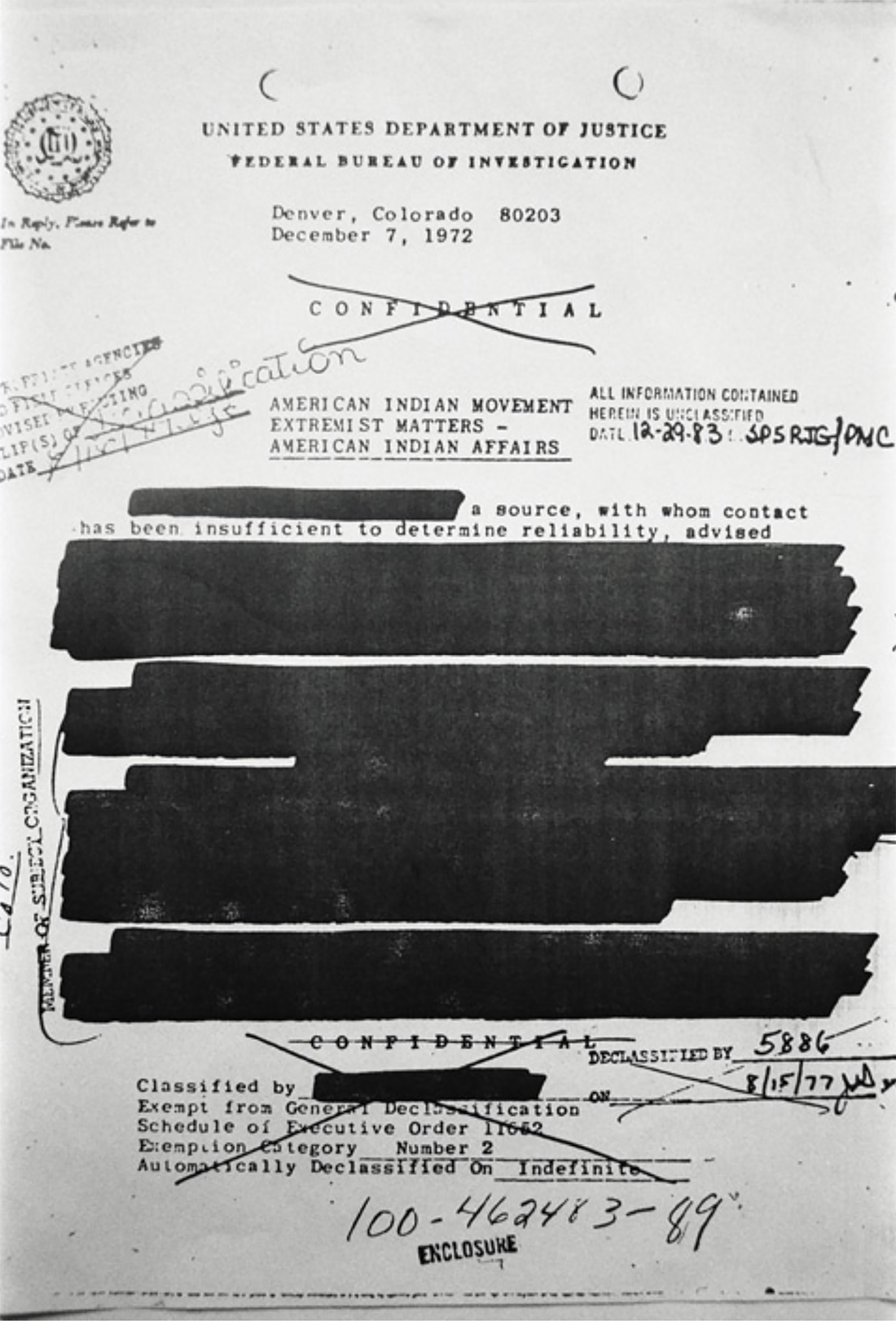

The four black and white photographs of Claxton’s AIM project are straightforward enlargements of declassified documents related to FBI surveillance of the American Indian Movement that Claxton found the New York Public Library in the late 1980s. Founded in 1968 in Minneapolis and given impetus by the American civil rights movement, AIM’s

Dana Claxton, 10 (2003). Single-channel video with audio, 8:00 minutes. Courtesy of Video Out Distribution/VIVO Media Arts.

objectives included the enforcement of existing treaties and recognition of sovereignty over their land. Their activities included an “anti-birthday party” on the top of Mount Rushmore (which is on Lakota territory), painting the Plymouth Rock red for Thanksgiving in 1970 and the 1973 occupation of the town of Wounded Knee, the site of an infamous 1890 massacre in which hundreds of Lakota men, women and children were murdered by the 7th United States Cavalry. The confrontation between AIM and the FBI at Wounded Knee included an extended armed standoff in which a number of people were killed. The validity of the trials that followed has been called into question as the FBI has faced allegations of evidence tampering and withholding information.

The documents Claxton has photographed are related to FBI reports on the activity of prominent AIM members, including Russell Means and Dennis Banks. The simple shift in scale from a letter-sized sheet of paper to a photograph five feet in height attaches a sense of violence to the enlarged, almost painterly gestures of the censor which block out much of the text. We can see the names of the individuals under surveillance, but nothing on the historical context of AIM’s actions, and nothing on the abrogation of the Fort Laramie Treaty, which guaranteed title over the Black Hills of South Dakota to the Lakota and Dakota. The sense of erasure signified by the mute black areas metaphorically alludes to not only the suppression of history but the character of a state in which the enforcement of “order” can be linked to such a document.

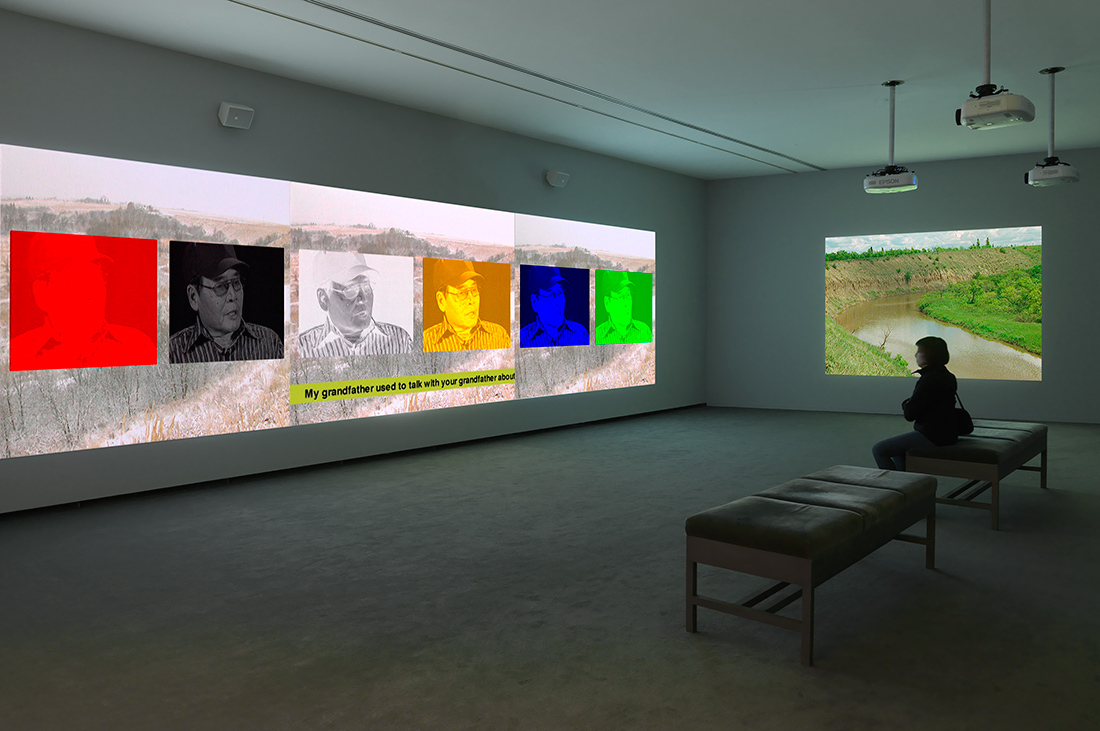

Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux (2004) can be seen as a companion to I Want to Know Why. A four-channel video commissioned by the Moose Jaw Museum and Art Gallery, Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux traces the arrival of Sitting Bull and his people— including Claxton’s maternal grandparents and great-grandparents—in the vicinity of Moose Jaw following the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. Three video channels, projected floor to ceiling and butted together side by side, present a constantly shifting collage comprised

Dana Claxton, AIM #2 (2010). Chromogenic print, 152.4 x 106.7 cm. Collection of John Cook.

Dana Claxton, Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux (2004). Four-channel video installation with audio, 34:10 minutes. Collection of the Moose Jaw Museum & Art Gallery.

of images of Sitting Bull, portraits of the Lakota who remained after he returned to the United States, ledger drawings depicting the Battle of the Little Bighorn along with a scrolling translation of a conversation in Lakota between two elders—Francis and Hartland Goodtrack—who narrate episodes from the lives of their people over the past century, including their sometimes difficult but often cordial relationship with the Euro-Canadians who lived in the area and accounts of their ancestors sitting around campfires with warriors who had fought with Sitting Bull at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Projected on an adjacent wall, the fourth projection presents a series of views over a rolling prairie landscape under bright summer sunlight. Initially, the landscape seems pastoral and mundane, an idyllic place where nothing much happens beyond the passing of the seasons. However, as the narrative of Sitting Bull’s exile unfolds through the installation’s audio and scrolling text, the location is identified as the site of the primary Sioux encampment—which at one point included several hundred lodges—where Claxton’s predecessors lived and her grandparents were married. The meaning of the scene shifts; the undulating surface of the landscape becomes a metaphor for both the absence of Indigenous perspectives from the principal accounts of the country’s history and the possibilities for locating suppressed narratives in the surfaces of the everyday. While the work is marked by the artist’s desire to connect with the past and it also implies a skepticism toward the conventional methods through which history is recounted. As David Garneau has noted, the narrative articulated in Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux,

is layered rather than linear, dialogic rather than authoritarian, and open-ended rather than contained. At least four accounts unspool at any one time. While they always complement each other and advance the story, the gentle polyphony encourages repeated viewings and the sense that we can gather only glimpses and should not imagine ourselves completely informed.7

Claxton’s engagement with questions of the absence and presence of Indigenous subjectivity finds parallels and intersections with the Anishinaabe novelist, poet and theorist Gerald Vizenor’s notion of “survivance,” a term that has become widely associated with the assertion of Indigenous identity in Canada and the United States over the past twenty years. Survivance is an archaic legal term that Vizenor has appropriated and, drawing upon Indigenous traditions of storytelling and the ideas of post-structural theorists such as Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard, re-purposed to describe an Indigenous mode of address that is neither an ideology or dissimulation but a form of practice that operates as “an active resistance and repudiation of dominance, obtrusive themes of dominance and tragedy, nihilism and victimry.”8 Survivance is a difficult term to define, one that deliberately avoids easy definition or translation, but is “invariably true and just … in native stories, natural reason, remembrance, traditions, and customs…”9 While survivance can assume many forms, its crucial feature is a sense of presence that emerges out of a rhetorical act to counter the historical absence and powerlessness established by and through the stereotypes and simulations of “Indian-ness” that circulate in the imagination of the colonizer. Survivance is not about memorializing the past but tracing continuity that extends from the past through the present to the future and, by doing so, it offers modes of personal and social renewal attained through “welcoming unpredictable cultural reorientations [that]…promise to radically transform current native life without requiring abandonment of the enduring value of their precontact cultural successes.”10

For Vizenor, the term “Indian” is an accretion of simulations invented by European intruders to separate the Indigenous peoples of North America from their tribal traditions. It both reflects a fictive homogeneity of the dominant culture and serves to contain Indigenous people within a false, racialized identity that has been “sustained in archives and lexicons as ‘authentic’ representations of indian cultures.”11 Vizenor proposes the term “postindian” as a more productive point of identification. The postindian, he argues, is knowingly bound in a relationship with the dominant culture’s perceptions of Native people and therefore enters into discourse anticipating that the encounter with stereotypical simulation is inevitable. These simulations, however, aren’t static but are open to alteration and replacement by new simulations that have the potential to upset the expectation of representation on which the stereotype is constructed. As Vizenor puts it:

The postindian warriors encounter their enemies with the same courage in literature as their ancestors once evinced on horses, and they create their stories with a new sense of survivance. The warriors bear the simulations of their time and counter the manifest manners of dominance.12

Dana Claxton, Blue Headdress (from Indian Candy) (2013). Chromogenic print mounted on aluminium, 61 x 46 cm. Collection of Robert Watson.

Or, as Winfried Siemerling put it in her discussion of Vizenor’s The Heirs of Columbus, “If access to subjectivity under dominance is mediated by this simulated other, one move towards healing leads through the creation of an other of this “Indian” (or indian) other in language and stories…”13

The strategy of intertwining the past and the present and creating new simulations to counter the “indian” stereotype as outlined by Vizenor runs through much of Claxton’s work. It can, perhaps, be most clearly seen in The Mustang Suite (2008) and her Indian Candy (2013) project. Taking impetus from the Lakota wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine or holy man) Black Elk’s (1863–1950) dream of the horse dance, in which the dance becomes a ritual of healing, The Mustang Suite is a set of five staged photographs of a contemporary Indigenous “family,” with individual images of Momma, Daddy, Baby Boyz, the Baby Girlz twins and a group portrait with the family on a blanket. Like all of Claxton’s photographs and “fire boxes” The Mustang Suite images are obviously staged and, especially when considered in relation to Claxton’s performance works, overtly embrace a level of performativity, both on the part of Claxton as a director and the “actors” she directs and depicts. Tradition is wryly brought into the present through the paint on Daddy’s face, an emphasis on red—alluding to Red Power and the sacred status the colour holds for the Lakota—in the family’s apparel and the traditional Lakota pattern on their blanket. Each member of the family is shown with an attribute refers to mobility and the horses of the Great Plains: a Ford Mustang car, a pair of mustang bicycles, a live pony and a Caucasian woman, who appears as the personification of history and wears red paraphernalia from BDSM pony play. The postures and clothing of the family members were chosen specifically to reflect a particular persona. Baby Boyz is “a young urban warrior who likes hip-hop” and, like his ancestors, “rides his pony bareback.” The twin Baby Girlz are hip but also wear mukluks and “help on the trap line when their grandfather calls” while Daddy could work “as a computer programmer and dances pow-wow during the summer.” Momma, “influenced by traditional woman’s dancing, medicine women, BDSM and burlesque culture” has “slightly humiliated history” and then lets it trot off, “never to be a burden again.” Taken together, this layering of references evokes a set of complex questions regarding history and the performance of identity while proposing a space in where tradition and contemporaneity offer the Indigenous subject the possibility to choose from “the best of both worlds.”14

Most of the images that make up the Indian Candy project—a ledger drawing showing Sitting Bull counting coup as he captures a mule wagon, souvenir cards from Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, correspondence ordering the arrest of Sitting Bull, a lone white buffalo on the open prairie, the acclaimed Osage Prima ballerina Maria Tallchief, Jay Silverheels playing Tonto in The Lone Ranger, an unidentified young man wearing a shirt, tie and feather headdress—are what Claxton describes as “archival images” that appeared in Google searches for images of the “Wild West.”15 Mounted on aluminum with no frame, the seductive glossy surfaces, intense saturation and confectionary colour of the prints gives them a fetish-like pop culture slickness. The emphasis on pixelation in the images highlights the layers and modes of technology that lie between the represented subject and the viewer of Claxton’s

Dana Claxton, Daddy’s Gotta New Ride (from The Mustang Suite) (2008). Chromogenic print, 127 x 157.7 cm. Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Purchased 2009.

work and, in some instances, takes on a patterned texture that has “an uncanny resemblance”16 to the beadwork traditionally produced by Indigenous women of the Great Plains.

The Indian Candy project can be seen as the assembly of an archive made up of pictures from other archives, in which acute remediation—as in the transfer of an image from one media to another—draws attention to and seeks connection with suppressed histories and subjectivities. In Blue Headdress (2013), for example, we can—with enough distance from the picture—just make out the image of a young man wearing a feather headdress associated with the Plains tribes, along with a suit or sports jacket, shirt and tie. The era is hard to pin down, but could be the 1960s or 1970s. There’s a formality to the pose which might recall some of Edward Curtis’ photographs from The North American Indian, but the young man’s clothing has none of the pseudo-authenticity Curtis employed. That’s about the extent of detail that can be made out, the heavy pixelation precludes the standard conventions of viewing an archival photograph, implying a wariness toward the history of picturing Indigenous people to a non-Indigenous public and emphasizing that what meaning we might take from the image is incomplete and speculative. Which is not to say speculation is discouraged, following The Mustang Suite we might wonder what sort of occasion is implied by the headdress and clothing, what elements of tradition and contemporaneity the young man was able to choose from and what acts of survivance he may have performed. This speculative character and the implied refusal to conform to the convention of Indian-ness, together with the project’s punning title and the playful use of colour, imply a potential for new meaning to be found in the remediation of the image and the reordering of the conventional systems in which images are categorized.

The departure from “accurate” colour in the Indian Candy works recalls the Kodak Shirley Card, a reference card with the image of a young Caucasian woman that was first used by Kodak in the late 1940s to calibrate the manufacture and processing of colour film, a method of standardization that was followed by other producers of photographic materials so that Shirley Cards, or an equivalent, were eventually used in photo-labs around the world. As a result, the standard tonal range of the colour film used in still photography and motion pictures tended to reproduce white skin better than dark skin. This was particularly evident in cinema, where white actors would have more of a screen presence than actors with darker skin. The choices made in standardizing these materials, as Navneet Alang has noted, “led to some people being able to revel in seeing themselves, but left others to look into a mirror and see no reflection.”17

There is both a parallel and a point of divergence between Claxton’s manipulation of the Indian Candy images and the recent work of cinematographers who have developed specific lighting techniques to overcome the Shirley Card bias in feature films and television dramas.18 While both seek a heightened presence for subjectivities that have been subordinated within the culture at large, Claxton has sought remediation—as in providing a remedy—metaphorically, in a move away from a “realistic” rendering of colour, while in more mainstream cinema the assertion of subjective presence is achieved through enhanced mimesis.

The central role of metaphor in Claxton’s work—as seen in the Statue of Liberty as an emblem of displacement in I Want to Know Why, the use of spoken Lakota to signify generational memory in Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux, the violence implied by the censor’s marks in the AIM photographs, the tongue-in-cheek references to horses in The Mustang Suite, among many other examples—evokes Vizenor’s discussion of metaphor as a mode of articulating Indigenous subjectivity that cannot be contained within established linguistic structures, instrumental logic or conventional Euro-American modes of understanding. Drawing connections between the tradition of oral storytelling and contemporary Indigenous literature Vizenor, citing philosopher John Searle, argues that metaphor allows for a more expansive mode of signification that moves beyond simple resemblance, and that “the knowledge that enables people to use and understand metaphorical utterances goes beyond their knowledge of the literal meaning of words and sentences.”19

Considered within this context for articulating identity, Claxton’s deployment of metaphor, her dialogical intertwining of Indigenous tradition and contemporaneity, use of punning humour, emphasis on the performative and refusal of stereotypes eloquently and forcefully demand the recognition of Indigenous subjectivities within the museum/gallery and the broader culture. In doing so she simultaneously offers the possibility for Indigenous viewers to see their reflection in the image/mirror and, for the broader culture, proposes a mode of communication in which “understanding is not simply assumed like it is in ordinary linguistic usage but … results from mental movements that mutually induce and open one another up and are interdependent.”20

NOTES

- Gerald Vizenor, “Introduction,” in Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998): 15.

- Scott Watson, “Whose Nation?” in Canadian Art, (Spring 1993): 40.

- Dana Claxton cited in Lynne Bell, “Dana Claxton: From a Whisper to a Scream,” in Canadian Art 27 no. 4, (Winter 2010): 104.

- Dana Claxton, “RE:WIND,” in Transference, Tradition, Technology: Native New Media Exploring Visual & Digital Culture (Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery, 2005), 16-17.

- Ibid., 17.

- Christie’s novel was first published in Britain in November 1939. Its original title, Ten Little N*****s, was taken from a popular children’s rhyming song. Concern that the title would be controversial led to it being changed to the, apparently, more acceptable Ten Little Indians when it was first published in the United States in 1940. Like the original title, this was taken from a children’s nursery song. The novel later appeared under the title And Then There Were None. Film versions of the novel appeared under all three titles. Ten Little Indians is still a popular children’s song, it can be found on numerous Internet sites, often with an animated children’s video.

- David Garneau, “Dana Claxton: Sitting Bull and the Moose Jaw Sioux.” Vie des Arts 197 (Winter 2004–2005): 93.

- Gerald Vizenor, “Introduction,” in Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 1.

- Ibid.

- Karl Kroeber, “Why It’s a Good Thing Gerald Vizenor Is Not an Indian,” in Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 25.

- Gerald Vizenor, “Preface,” in Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), vii.

- Ibid., 4.

- Winfried Siemerling, The New North American Studies: Culture, writing and the politics of re/cognition (London: Routledge, 2005), 93.

- Claxton, cited in Amber Berson, “Dana Claxton, The Mustang Suite and Hybrid Humour,” Amber Berson’s website, https://www.amberberson.com/academic-writing

- The images of the ancient petroglyphs that depict humans and animals that make up the other component of the project were shot by Claxton in Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park / Áísínai’pi National Historic Site in Alberta.

- Dana Claxton, “Artist Statement,” in Dana Claxton: Indian Candy (Vancouver: Winsor Gallery, 2013), 6

- Navneet Alang, “Ways of Seeing,” The Globe and Mail (Toronto, ON) January 27, 2018.

- Alang cites the example of Ava Berkofsky, the director of photography on the current HBO drama Insecure.

- From John Searle “Metaphor,” cited in Vizenor, “Aesthetics of Survivance; Literary Theory and Practice,” Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 13.

- From Werner Kogge, “Die Grenzen des Verstehens,” cited in Helmbrecht Breinig, “Transdifference in the Work of Gerald Vizenor” in Native Authenticity: Transnational Perspectives on Native American Literary Studies (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010), 127.