Christina Battle and Serena Lee, Shattered moon Alliance: Toolkit for Time Travel (2018). Installation view, YYZ Artists’ Outlet, 2018.

Jayne Wilkinson

MEDIATED DISASTER

AND UNMEDIATED CLIMATE ANXIETY

A CONVERSATION WITH CHRISTINA BATTLE AND JAYNE WILKINSON

Jayne Wilkinson: One of the purposes of this collection is to address the practices of First Nations, Métis, Inuit, racialized, differently abled, or LGBTQ cultural producers and media artists, not through an “anti-canonic” view but by mapping an alternate set of discourses for the work. So, I’ve been thinking about what it means for artists to be working outside the canon, and what it means for artists to think alongside and be in response to established, “canonical” works, particularly in film and experimental cinema. The idea of canonization was so thoroughly debated in postmodern art criticism but, at the same time, canons still exist and are perhaps now more insidious in how they operate. It seems in some ways antiquated and in some ways urgent. If we say that all art practices are equally valid and worthy of consideration but we still don’t pay attention to the works of POC artists, writers and filmmakers, then the production of work is still being guarded by a certain kind of valuation. With your work, this seems like a relevant place to start because you’re continually pressing against the disciplinary divisions that define a canon, and your work is often questioning those divisions—what is media, what is collage, what is film, what is digital art? Are these questions important ones for your practice?

Christina Battle: It’s interesting, this question of the canon. Quite honestly, I don’t know that I’ve ever really thought about it much. As artists, we’re continually immersed within it and consumed by it, I just don’t see myself as needing to engage with the determinations as much and I’ve frankly just ignored it from the start. I’m interested in working with ideas, in thinking about how greater society operates and how it might do so differently, how it might be better. How we as artists might contribute to shifts in the larger communities that we operate within. The notion of an artistic canon is in such opposition to this line of thinking. In addition to how I was brought up to think about and challenge the systems we exist within, I think I come to this because of the roundabout, sort of DIY way that I came into art. I came to think of myself as an artist kind of late. Doing an MFA was a deliberate decision I made in order to take this idea of being an artist more seriously. Now that I’m living in Edmonton again, I’ve been reflecting on this a lot. Since moving back, people ask me about how long I’ve been gone, and when I left and I recently realized that I always say something about how, when I lived here when I was younger I wasn’t an artist, and that I’m now coming back as one. But really, before I left Edmonton—before I had made this deliberate decision to think about artistic practice more seriously—a lot of my life was situated around organizing with friends in the craft and punk communities, making stuff and selling it at art fairs and festivals. At the time, I didn’t think of myself as an artist though, and I had very little exposure to the art scene. Now, I realize, that I actually was engaging with the arts just in a different way—reflecting on this of late, I’m asking myself what being an artist even means.

JW: Do you think that “artist” is an institutionalized term now? Whether or not one identifies as an artist has a lot to do with the aspects of professionalization that come through doing a degree (an MFA, or even a studio PhD) and then showing in a professional gallery. But identifying as an artist can also be about being punk, going against the status quo, making work that doesn’t fit in a professional setting, making your own space. In the context of the industry of Contemporary Art, to say one is an artist is almost more like a job description. It feels like it has become something else.

CB: Yes, I mean, now I’m wondering why I felt that I needed to follow the route of institutionalized education as a way to take art more seriously for myself, and in order to call myself an artist. Really, I wanted to know more about the artistic sector and to figure out my place within it. I think part of it was because I was making films. I went to Ryerson part-time for film studies, but we were being trained more from the lens of expecting to work in more Hollywood-types of filmmaking. I was lucky in that, at that time, we were still learning how to make film on film and editing on flatbeds, which I think offered a really different relationship to the physicality of film, and thinking about filmmaking as a whole. Eventually I stumbled into experimental film by becoming a member at LIFT, I sort of instantly dove into organizing screenings and events and being a part of a community. That was when I learned that an MFA even existed, before that I had no idea. Before that I had been in the sciences, I never went to art school. So in terms of being a capital ‘A’ Artist, I think the definition shifts depending on your relationship to art, and how you’ve come to it. Professionalism is definitely a part of that but, like, what does professionalism mean? It could be so many different things.

JW: I agree, to me a professional practice is one that is about leading a conversation. One that is, despite disciplinary boundaries, carrying the potential of being radically experimental. I think that’s where collaboration enters too, especially for artists working between disciplines. You have some longstanding collaborators, you have some projects that essentially crowd- source collaboration and ask your audience to become a temporary collaborator, and you have practices (like gardening/working with plants) that are invested in growing an art community and, I would say, is a form of artistic practice that is little recognized.

CB: It’s an aesthetic and world-making practice.

JW: How did collaboration come to be such an integral part of it?

CB: I think it comes partly from the DIY crafting and alternative scenes that my friends and I engaged with while I was in Edmonton and partly from working in experimental film, where the practical needs of making a film often necessitate working with other people to help make your projects happen. I tended to gravitate toward making films on my own so,

for me, this generally was more about needing a community, of having like-minded folks around who are also interested in making films to lean on and build strategies together for seeing and showing one another’s work.

JW: Do you think working in the sciences also informed your need for collaboration?

CB: I think for me the collaboration part is less prescriptive, it’s a way to fill the needs of a project and still be allowed to sort of work on my own, while also engaging with others who are working organically in similar ways. It’s not really dictated first by thinking about collaboration as a way to generate artwork or form certain types of things. It’s more like: what do we, these few people who are together right now, what do we want to do together? Collaboration with the end goal of making an artwork is somewhat new to me. The collaborative work I’ve always done has been more events driven or organizationally driven. One of the first collaborative projects I was part of when I first lived in Toronto was The League, which was a group of four women who were experimental filmmakers: Sara MacLean, Juli Saragosa, Michèle Stanley and myself. We decided that we wanted to work on film projects and events together and we became friends through the project. We would come together at someone’s house or the editing studios at LIFT to make things at the same time, working alongside each other while still working individually. Then we would organize what ended up being, basically parties where we presented the film loops and works that we had made. So I guess the end goal was an art event of sorts, but it was also something else.

JW: It sounds like a very feminist practice actually. Although I imagine that was not necessarily how you were thinking of it?

CB: Well, somewhat. I don’t want to speak on behalf of Juli, Michèle and Sara, but I think it was partly about saving ourselves time and energy, because we wanted to see our friends and hang out and we also wanted to work, and it was hard to be able to do both of those things. It wasn’t “social practice” as the art world has come to call it, it was more about sharing resources and sharing energy. But because we were doing so outside of institutions, I think we felt like we had the freedom to just make work without consequence. We definitely came together, quite deliberately, out of a need to escape what was a very male dominated experimental film scene. In some ways, the very fact that we wanted something different allowed us the freedom to try something new and not feel so bound to larger expectations. I think it does, in a way, come back to a question of who are the keepers and conveyers of knowledge in an art scene, who perpetuates what we understand as “good” or “beautiful” art. Or even just the things we’re exposed to. Ultimately, I think we were just trying to do something different because we didn’t exactly fit in to the way things were. I don’t think we ever discussed it or reflected on it from the perspective of a form of artistic practice or anything like that. I mean, we were surely not the only ones working this way at the time, but there also weren’t a lot of similar models we were aware of in the larger film community that we were part of. I think it’s only really after the fact that it could be contextualized as a particular collaborative or collective model part of a broader artistic legacy.

And, in some ways, this is what often happens, mainstream culture always picks up frameworks from counter-cultures and subcultures, and turns them into something different. But at the same time, if those ideals are trends, like if suddenly it’s trendy in the art world to work together and collaborate, and care about each other, if it’s taken up in the right way, it could be transformative. I feel like it’s yet to be seen if it will be.

JW: Maybe there’s a bit of a false opposition in setting it up like this, but I think there is a parallel between capital ‘C’ Contemporary Art and this professionalization of what it is to be an artist on one hand and then what you’re talking about in terms of just doing the work, doing projects, making things happen on the other. This way of working collectively has been well incorporated into the art world now, but the problem with trends is that they can dissipate so quickly. So, for example, right now the attention given to care and hospitality, the questions around social practice that came out of relational aesthetics, and that trajectory of theory, well, what happens when this is no longer current? We should still be caring about how we work with each other, advocating for each other’s like health and well-being, all of these things. I’m a bit dubious about it too.

CB: I think that’s a perfect example and I think about that a lot right now. Especially this focus on care, which, of course I think is lovely and necessary. But also, it’s so fucked up that people don’t already know how to do that! Like, how is it possible that neoliberalism has worked so thoroughly that we don’t know that we should take care of each other, or our friends, our co- workers, our families? How is it that we need to re-learn this? We already know this!

JW: Yes, exactly, care is also work. Everything is work. And if everything is work, everything requires compensation. Or reciprocity at least. A colleague pointed this out to me recently. So, you talk to your friend, that’s emotional labor; you exercise, that’s physical labour, or self-care; you talk about your ideas, that’s intellectual labour; you go to work and of course that’s labour, and certainly you expect to be paid at work. But then when you’re at home, when you check your email, when you post on social media, is that work? Personal branding is definitely work. So, when are you working and when are you not? It’s interesting to note that this rising concern about care in the art world is happening simultaneously with a shift in the ways that we work together, because institutions are caring for us less. It’s fine to say that we want to be extending gestures of care toward each other more visibly and obviously in contemporary art practices, but what about institutions? What about ensuring that we are creating ethical and sustainable workplaces? What about reinstating unions more widely? What about legislation around how and when people get paid and compensated for the work that they do? When does work stop? We’ve lost sight of some of those basic protections for workers’ rights that we had in the twentieth century and we don’t have any more.

CB: And are we just being distracted from thinking about those things by focusing on caring for each other rather than the fact that our work, actual labour, isn’t compensated, isn’t secure, isn’t stable? THAT is maybe what we should be focusing on. Because that is also a form of care. Everything’s individualized, and that’s how neoliberalism works: everything is an individual’s job, everything is an individual’s fault.

JW: The state stopped caring for people because it had to start caring about corporations first, and so the basic requirements of survival are entirely the work of the individual. When you think of all the work that goes into preparing an exhibition—by the artists and curators and administrators and technicians and staff—it is tremendously important to recognize, through gestures of care, the work that each other does. Because that work is difficult, uncertain, and underpaid. In some ways, your practice, coming out of DIY organizing, recognizes that we do need to do a lot of the support work ourselves. Could you talk a bit more about the other side of that shift, after you finished your MFA? I think there is an interesting parallel between the way of working you described earlier (people working separately but together) and the kind of collage and mash-up aesthetic that you incorporate in your videos, and even further how digital collage and combining readymade texts and images has come to, more recently, translate into total installation environments (like in the SHATTERED MOON ALLIANCE exhibition at YYZ Artists’ Outlet in Toronto).

CB: I think a lot of this method of working was derived from being an artist in Toronto; a lot of it was dictated by some of the problems that are still going on in Toronto now (albeit on an inflated scale)—living in a large city without access to space, or time. When I come back out west and whenever I’ve lived out west, I tend to make work very differently. Usually it means taking a camera and pointing it out at the world. Whereas, when I lived in Toronto, and in San Francisco too, my practice looked much more like sitting in a dark room and working with whatever I had access to. Usually that meant pre-existing images, like using magazines, working with found imagery. Nowadays it’s working with the internet and sourcing material from computers and online. In some ways, I feel like it’s because of a lack of resources, not having the space to work, not having the time to work. And also wanting to work with others and coming up with strategies for doing that. With SHATTERED MOON ALLIANCE (SMA) specifically, I think the method of working comes from the act of collaboration itself. SMA is a collaboration with Serena Lee and, since we’ve been working on the project, we haven’t lived in the same city. So, a lot of our time is spent thinking about what it means to be making something together while separated across space and time: making work together while apart. Our strategy is one that pieces things together, in a sense it is a form of collage that brings together a bunch of elements we’ve been working on individually but through a shared and collaborative framework.

JW: I’m thinking too of BAD STARS, your exhibition in 2018 at Trinity Square Video. That installation was a very totalizing kind of environment, with crowd sourced elements and a continuing collaborative question around how we define and understand disaster. And it’s very interdisciplinary, including video installations, text-based work, collage, wallpaper, appropriated images … I’m curious about the relationship between digital collaging and building exhibition environments with multiple elements.

CB: I do really like working with space, and shaping spaces. I think that there is something that I’m interested in thinking about community in the same way. I’m really attracted to narratives in film and video but my approach is to try and shape them in less linear ways. When I started making work I was making single-channel film and video work for the

Christina Battle, BAD STARS (2018). Installation view, Trinity Square Video, 2018. Photo by Jocelyn Reynolds.

Video still from Christina Battle’s, BAD STARS (2018).

cinema and always struggled with endings (I never remember the endings of movies—like, literally never!) Once I started working more with loops I felt this freedom to expand narratives across both time and space. I still sometimes make more linear based works for the cinema and enjoy doing so, but in general, I’m more comfortable working with fragments of materials and spreading them out. And in thinking about how audiences might move through a space and experience a narrative on their own terms.

Nowadays, I think collage in my work is really dictated by thinking about technology itself, about how technology shapes all of these things—how it shapes our ideas of community, our ideas of space and our ideas of what images look like. Or should look like or could look like. The collage comes in through wanting to think that through and often means pulling imagery and source materials from different forms of technology. I’m really pre-occupied with Google Earth as a way of thinking about how the world is or looks. Collage makes perfect sense to me as a way to think through those ideas.

JW: A really important part of your process right now is working with the view from above, working with satellite imagery through Google Earth, and how that has shaped or changed your personal perception of space. Google Earth is a tool and a technology that is changing our relationship to the world around us in really still very uncharted ways. I’m interested how that comes to inform the work.

CB: I’m interested in what you just said about it being uncharted: what are the implications of this, of the idea that we can all so easily have a view of the world that has never existed before? But it’s a view that is proprietary and copyrighted. We tend to think about it as a tool to help us move through the world and move through space, but we don’t think nearly enough about what it means and how it changes the way we view the actual or real world. I hesitate to use the word “actual” because Google Earth and Google Maps are a part of the actual world. They are virtual tools that are actualized in reality every day. It’s just that their use is, as you said, uncharted. I’m interested in thinking about that shift, and trying to hold onto it, trying to map it. Because I feel like there will be a day when we look back and realize how we kind of fucked it up.

JW: How so? What do you mean?

CB: What I think we’re even seeing now is how our relationship to the Earth is so far off from a real relationship, is distanced from any kind of relationship of care, or even self- interest. And I think that’s because we navigate the world in ways that are controlled by technology. Humans have very selfish reasons to care about the earth. It’s hard; I clearly love technology, and use it and need it. But we haven’t really thought through what it means to have a relationship with the natural environment that is entirely mediated—think for example of somewhere like Banff National Park, where people can easily look at thousands of pictures of it online or explore it through Google Earth from this bird’s eye perspective and think they have an understanding of it. That isn’t a real view, it’s a composite, constructed, impossible view. And this is how we are engaging with environments now. I’d like to think that having experiences with nature changes the way you think about land and issues related to the environment. That might not be necessarily true, but I do think it helps.

Christina Battle, the view from here (2019). Large scale collage project, Capture Photography Festival, 2019. Photo by roaming-the-planet.

JW: I don’t know. I mean, I share that opinion. When you have an experience of the natural world that is unmediated, it does change how you think about those spaces, how you engage with non-human species. But an unmediated experience is increasingly impossible and I would say perhaps we’re already at the point where you can’t have an unmediated experience of the world—ever. We are forever tethered to devices, even when they are not physically with us. Say you go out for a walk without your phone, you are still very conscious of functioning as a human who regularly uses a digital device to map their location in space. For people who navigate urban spaces—which I realize is not every human, but for the vast majority, especially in a country like Canada that is increasingly urban by percentage—so for a very large segment of the population of the world now, wherever you are, your habits are digitally conditioned. How, now, can we have experiences that escape that conditioning? It seems impossible. We’re changing proprioception. The brain maps itself in space differently when it has to remember where it has been, rather than simply listening to a digital voice say “turn left, go straight, in 200 metres turn right.”

CB: Technology didn’t have to be like that, it doesn’t have to be like that. It’s a question of, is it inevitable, or do we want to make room for unmediated experiences? It could be different if we thought of technology differently, but because it’s so tied with capital and economics, we are conditioned to use it, continually. How we rely on our phones, for example, and how they have become status symbols, is directly built into their planned obsolescence. There’s this commercial for iPad out right now that drives me up the wall. It’s this guy. He’s clearly a “creative.” He’s drawing on his iPad and meeting with people, eating, walking, taking the subway all while working on his iPad. It ends with him on an airplane. And when everyone else on the airplane has to put their work away and their computers away, he can still work because he’s got an iPad. It completely embodies this idea that you can never have a break from work. That’s what is being sold to us, and it’s at this level of coolness because he’s a creative—it’s just so wild to me. It is a perspective entirely dictated by a Western colonial model driven by capitalism; by white supremacy. It doesn’t have to be this way. If it wasn’t so necessary to be so all-consumed by our devices, maybe we would have a different relationship to technology. If there wasn’t this drive to constantly be updating your status and to share pictures of where you are in the world right now and how cool it is through Instagram, maybe we wouldn’t engage with our phones when we’re in the middle of the desert or the forest or wherever. And maybe we could have experiences that were entirely different.

JW: This is one of the biggest collective anxieties of our age I think: technological anxiety. We fear how our relationship to it is changing what it means to be human. And that fear is intersecting with the climate crisis in really significant ways. The climate crisis is this looming, inevitable thing in the social imaginary. But it’s also just happening. I mean, the Earth is changing, humans are changing, ecosystems are changing. We are not able to disconnect from ourselves enough to connect with other ways of being. I think you’re right, because of the way that that capital has taken control, so thoroughly, of science and of the production of technology, we can’t disconnect from it. It’s a trick of advertising to think that working all the time is aspirational; I think that’s very scary. Artists, or “creatives” are not, like, idea machines. It’s not automatic, you don’t turn it on and off. Often, the best ideas come when you aren’t working, when you’re doing something else, focused on a small task or using a different set of observational skills.

CB: Definitely. And the way technology is developing, because there is so much value and capital attached to it, whether it’s financial capital or social capital, we rarely question whether it’s useful to us, or whether it’s dangerous or not. That doesn’t really come into the equation. Even though there’s a lot of scholarship about technology, and a lot of conversation around it. These are tools that are entirely polluting, composed of minerals that are dangerous to extract, and that will ultimately end up in some landfill somewhere—somewhere where most of the people are Black or brown and where poverty runs much more rampant than here. It is like this ridiculous racket, that we, that I, completely engage with.

JW: That’s a really critical point. It’s perhaps not new to point out that artists use technology in order to critique it, but is that important to you—incorporating theories of digital technology and then using those technologies in order to be critical?

CB: Yeah, it’s tricky. It’s incredibly important to me to critique it, and I do think we need to be thinking about these things. But then at the same time, it’s … it’s … I don’t know, it’s a bit futile, I mean none of it seems to be looking very good does it? [laughing] So many people are talking about these things, writing about them, teaching classes, criticizing the government for not doing enough, criticizing the corporations for putting us all under constant surveillance but what dent is that having on this massive machine? I’m constantly throwing

Christian Battle, Water once ruled (2018). Video, 6:14 minutes.

my phone at the wall (metaphorically) but I think it’s important to have the conversation and critique the system, and to try to insert that criticism into as many spaces and within as many conversations as possible because otherwise, you know, what’s the alternative? That we just give into it and accept it? To me that is much scarier.

I spend a lot of time on Twitter and you know, it’s a nightmare most of the time. But I think the amazing thing about Twitter is that the nightmare is continually exposed. That can be aggravating as hell because you know, we’re all screaming about all of these things that are happening to one another, and with one another, and all these exact same terrible things keep happening again and again. And still we have to continue. But without it, I feel like we wouldn’t know that a lot of other people are also screaming. There is value in that. Also in the way that it has given a voice to those otherwise marginalized by mainstream society. And in watching others discover (somehow for the first time) the traumas and the violence happening in communities that are marginalized. There is value in that. I’m just not sure where it leads. There are such powerful forces that are working against us.

JW: Twitter is an interesting forum to observe—to telescope out from the myopia of the screaming-at-each-other part and to think about what it means to have a public forum where the individual content is very short but the conversations can be very long. Those limitations are fascinating. It’s totally a Fluxus medium. I realized that by following Yoko Ono’s Twitter feed, it’s the perfect medium for someone like her. Does Twitter as a social sphere inform your art practice? Artists are often so accustomed to working with constraints, and I think a lot of incredible work comes from that. I’m thinking of a connection to your text-based work (like the notes to self project) and the way that you use text and like the billboard projects for example (the view from here and Today in the news more black and brown bodies traumatized the soil is toxic the air is poison), or like the the future is a distorted landscape project at Nuit Blanche Toronto. Maybe the Fluxus connection is a bit strange…

Video still from Christina Battle’s, Note to Self (2014–ongoing).

Video still from Christina Battle’s, Note to Self (2014–ongoing).

CB: No, I think it’s bang on. I’ve been thinking a lot about the Fluxus movement lately. I recently taught a class about technology and what it means to be a contemporary media artist living with the internet. The majority of the class focused on Fluxus projects. There is definitely this natural affinity. I think a lot about Fluxus scores. I hadn’t thought of how I incorporate text within that particular framework before but it definitely does make sense thinking about the ways in which I appropriate text. I tend to massage the texts I’m working with much more now than I did before. I used to be very hard-lined about it; I would appropriate text and leave it stand as a readymade. I still do that, but now I’m more interested in how my own voice can also be a part of it. But then it’s also thinking about this moment that we live in and wanting to reflect it back at itself. For me using text is a way to help ground imagery. It also allows me to experiment with imagery in ways that can allow the images to be more abstract, but then still have a trajectory of meaning. That’s important to me.

JW: You work with image/text combinations in a way that is very digitally oriented. When we’re online—looking at websites, on social media, producing content for our own media streams, messaging and group chatting—we now have a very sophisticated understanding of image-text relationships. I think we’re much more versed in those possibilities, as consumers and producers, than your average magazine or newspaper reader in the ’80s or ’90s would have been. Those are specific skills, being able to use memes and tags and images and videos together to communicate meaning, to make an idea legible. You use image-text combinations very specifically to abstract ideas, often to move away from legibility, so that the viewer has to do some of that interpretive work themselves. I think that’s true when you’re working with still images, like the billboards, or with moving images in video, or with the GIF projects—it’s all very much informed by an idea of digital collage that is akin to the collaging of life that the internet has become. And we all see a different internet, one that is specific to our (narrow) ideas.

CB: That’s why it’s important to me that I’ve had the chance to work more in the public sphere, and to be able to engage with people at street level. When someone enters a gallery, that already shapes their experience, the very fact of being there. Making work out in the world, in public, I’m interested in considering how people will engage with the work, or not. What will they think about? How do I start a conversation with someone who might not even want to have a conversation? It needs to be directed by the work either by the text or image or a combination.

JW: The visual field of public space is so full, so working in a public-facing way, you really have to, sort of, arrest a viewer for them to stop and engage and think about what you’ve proposed. You’re right that the viewer who comes to the cinema or the gallery is already prepared to receive art, to have an art experience of some kind, so they are already captive. The screen-based world is somewhat in between, since I don’t think there’s necessarily a difference between IRL and online anymore, it’s all part of the same, hyper-mediated world we exist in. We’re bombarded with images and ideas that like often we don’t want to see, or don’t ask to see. At the same time, what is available for us to interact with online is increasingly limited. We need to have our viewing spaces interrupted, and I’m interested in how art can do that, and to what ends. On the other hand, artists are always working in public to some extent.

CB: But it’s different publics, right? An art gallery has a very different public than exists in a public space, whether we want to acknowledge it or not. I think that’s why I’ve been thinking about the Fluxus artists and movements so much, why their trying to disrupt our expectations of art, and challenging the way we approach working with audiences makes so much sense to me. It’s just so different now because so much of our public sphere is online, but the tactics I think are still really relevant. It’s like the playbook already exists!

JW: I wonder if there’s a way to take that idea of interruption, of disrupting the visual and virtual space, and map it onto the questions of climate fatigue and climate anxiety. I’m thinking of your work around disaster, and its relationship to both the natural world (through natural disasters) and our highly mediated world (through the representation of such disasters). It seems that escaping from the attention economy, finding a way to intervene into our perpetual distractions, is one aspect of what art can do in this moment. Another is to get us out of the malaise around what’s happening to the environment. It’s so easy to continue on with life and think, oh well, I hear the news, I know what’s going on, it’s all happening, we’re all gonna be fucked and that’s it. Which of course, isn’t going to help, at an individual or a collective level. What do you think the role of art is in thinking about climate?

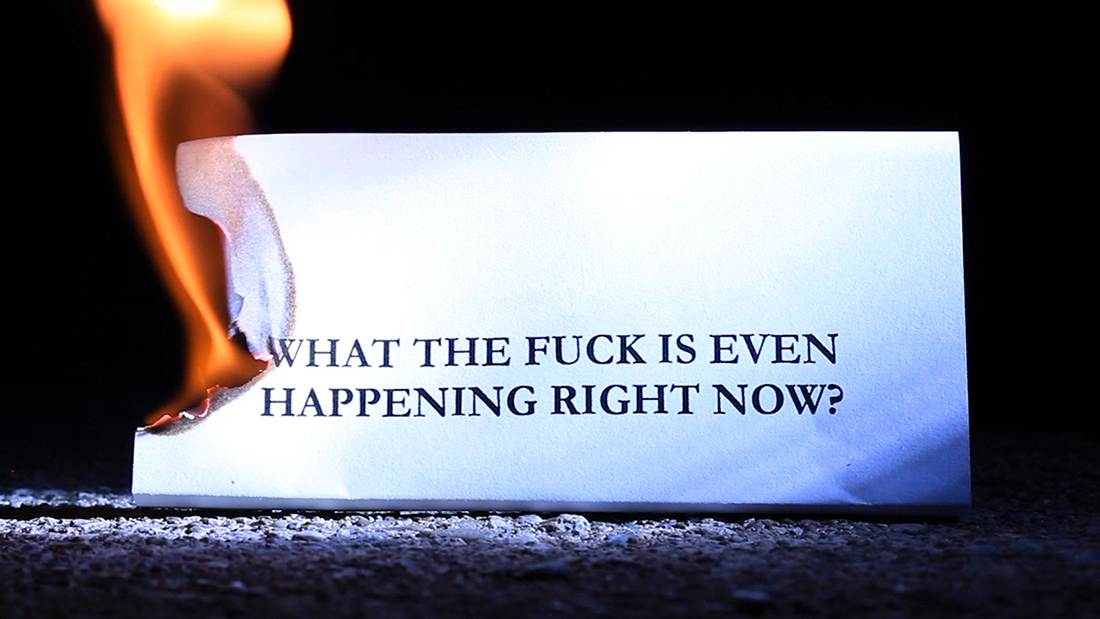

CB: Well, thinking about the climate crisis is, necessarily, also tied to thinking about all of the other global crises. They’re all wrapped up in the same development and history— colonialism, capitalism, white supremacy. Climate encompasses everything, but it’s hard to think about it, to define it, to tackle it. Here’s an example. I constantly read Twitter feeds and comment threads about climate change, which I both love and hate to do. I’m interested in knowing, what do people think about this stuff? How do people think about environmental crisis now, what are their ideas about it? There was a CBC article posted a few days ago.

Christina Battle, the future is a distorted landscape (2017). Multi-screen installation, Nuit Blanche Toronto, 2017. Photo by Henry Chan, courtesy of Nuit Blanche Toronto.

I don’t even remember what it was, it actually doesn’t matter but it basically said, once again, scientists have realized that we’re fucked. We’ve all read a version of this story many times now. And I was reading through the comments and the thing that was new, that I hadn’t seen before but that really struck me, was how cynical and humorous they were. People just turned it into a joke. It wasn’t denial, it wasn’t that the ‘scientists are lying to us,’ or ‘this is an exaggeration,’ which is what we are more used to seeing from climate change deniers, or even that ‘jobs are more important.’ It was turning the death of the earth into a joke. To me that was very telling, although I’m not entirely sure of what. There is something so absurdly bizarre about this, that this is how your everyday person is responding to a very serious article. And that’s very troubling. And, I think indicative of the difficulty the collective ‘we’ has of grappLing with the crisis and how fucking huge it is. I haven’t seen this response utilized to this degree before, but it also seems inevitable. How do we get over this? Or, how do you switch the conversation and the narrative back into something else? Because humor is quite deliberate. And, I think the humour is also tied to this new language we have because of engaging online.

JW: I mean, humour is a coping strategy.

CB: Exactly, but it’s not knee-jerk. To make a good joke is deliberate, right? And these people were making great jokes. They were terrifying but it was also profound. This is the way we respond now. How do you help people get truly in touch with the reality and the fact that we’re killing ourselves and each other? I don’t know. I feel like we’ve been doing it to ourselves for so long.

JW: The narrative of climate change in the mainstream media has really shifted, especially in the past year or two. It used to be that environmentalists and activists were driving a lot of the conversation, and the media would pick up on that. The story was that environmentalists, not scientists, but environmentalists were concerned, activists were concerned. It was almost seen as fringe. The media would report on topics (like acid rain, deforestation of the rainforests, sea level rise, endangered animals, ice caps melting) but climate change denial was very real, especially through the 1990s and 2000s. At some point in the last few years there was a very quick shift from the main narrative being one of denial, that the scientists were wrong, to acceptance, where the scientists are right but we just don’t or can’t care. Now we have hundreds of thousands of scientists in every part of the globe regularly telling us that environmental collapse is imminent, that global warming is happening, that we are living in a dangerously unstable world. There are regular reports to the UN, summits and conferences and very well publicized global protests and still, we don’t care. So, the response of humour that you bring up is a remarkable and understandable shift. It’s a way of processing grief. We’re grieving. And we’ve finally reached the acceptance stage, but instead of action, which seems impossible, we laugh at it. It actually makes a lot of sense.

CB: One thing I think about all the time is this slow pace of change. I did my undergrad in Environmental Biology and at the time the program was totally new. I took a plant biotechnology class where we were learning how to genetically alter plants. Which seemswild but it was essentially just a kit that we used in the lab. You would pick some plant cells put them in one tube, add some enzymes, shake it up and then you would have altered the genetics of the plant. And I remember talking to my parents about it and saying “I’m 18! It’s so weird they let us do this!” I say this because clearly plant genetics had been going on for a long time by then, if they were letting undergrad students test it out so easily. I graduated from that program in 1996 and even then, with the incredible knowledge of plant and animal biology that we had at that time, it took so, so much longer for environmentalism to enter mainstream discourse and everyday conversation. It’s only been relatively recently that we’ve been having the conversation collectively. So you’re right, it did happen very quickly, that we have been going through these emotional stages, as a populace.

JW: So what can art do in this context? Because art often produces and responds to very emotional states. It gives us experiences and opportunities to really think about who we are, where we are, and to me it feels like that’s an important thing if we can’t have the experience of being in nature anymore, which maybe we can’t.

CB: Definitely, and I mean, I think that that’s also maybe why, I think us continually coming back to thinking about the Fluxus movement as we’re talking is interesting, it’s like it’s necessary. The conversations that artists are having are necessary.

JW: This reminds me of Khalil Joseph’s BLKNWS (2018), which has some interesting resonances with your work. It’s a two-channel video mashup installation with clips taken from YouTube, some very famous and recognizable and widely circulated, some not, alongside segments filmed at news desks with actors portraying the anchors. All the clips were somehow connected to representations of blackness in the news, many intersecting with representations of climate disaster: hurricanes (like in Puerto Rico), class relations in the US, border issues. But there was also a lot of humour too. There were moments of understanding, of trying to find commonality beyond your own experience, of recognition that we still have these relationships that we have to form with each other. Even if, in the same minute that you see something affirming, then you are confronted by something incredibly difficult immediately after. It feels like that’s what it is to live right now.

CB: And that’s the problem too, we’re just so fully immersed in it. We’re so embedded in it, and so affected by it. It’s hard for people to see beyond their own lives, to have that external perspective. That’s why I think it’s important to use tools and technologies in critical ways. We do have an external perspective, we do have the capacity to see the larger scope, but it’s not always in the way that we need. I’m not so naive to think that some technology is going to be the thing that saves us. I don’t think that’s possible. But in terms of our perspectives, it’s like, how do we step outside of this thing called colonialism and white supremacy and really see it? Not just see it for what it’s leading us toward, but see alternatives to it. I think art has the power and the potential to show us these other ways, or possibilities. And the possibilities and the potentials might not work. They might not ultimately be the right thing. But at least we’re engaging in this way of thinking through these other potentials. Because otherwise, you know, I don’t personally think that we’re going to save ourselves from within the system that we’ve already developed. I just don’t actually think that’s possible. And, I don’t know if it’s possible to shift into some other system for some other way of thinking and some other forms of knowledge in time or if that’s possible either but I just feel like, shouldn’t we at least try?

JW: I agree, I don’t think the system that we built for ourselves is the one that we’re going to be able to use to fix the problem, but let’s not stop trying to think of other ways.

CB: Building the structures for other potential ways of living, even on a micro scale within the arts or however you want to frame it, is so important. It will be necessary, I really think that. Because I think we really are still in denial. Even though everything is burning. And we literally can’t breathe the air. I’m in Edmonton and I watch the air quality warnings all summer now because of the ongoing forest fires up North.1 I didn’t believe this entirely before but now I do: the majority of people really don’t care about stuff until it happens to them. I didn’t want to think that was true, but it is. And eventually everybody is going to experience extreme flooding or fire or a tornado or whatever other crisis becomes a result of climate change. They just are. So when that happens, I think having alternatives already worked through or thought about, or discussed—that’s when they can be picked up and utilized.

So that’s why I’m thinking about disaster as this tool for actually changing society in a positive way. Moments of crisis are the moments that capitalists exploit, right? That’s when, like in New Orleans, massive swathes of Black populations were pushed out and the real estate began to be developed in different ways. They exploit moments of crisis. They’re successful at doing it because in those moments, that’s when whatever is laying around gets picked up as the next thing or the next idea. Artists have to do it too, to have the next idea in place already. It’s sort of like a toolkit to use at some point and you know, obviously I’m glossing this all over a bit. It’s a bit rosy to think about things actually working in that way. But at least that’s something.

JW: No, I think that’s true. Rebecca Solnit talks about this in Hope in the Dark, which was first published in 2004 but has been updated in a few editions since, and it remains so relevant. In the new preface, she writes that “A disaster is a lot like a revolution when it comes to disruption and improvisation, to new roles and an unnerving or exhilarating sense that now anything is possible.”

CB: I think that’s what’s needed, right? As a society, we don’t listen to the people who have alternative ideas—those that have just ideas. They’re not the people in power. But I think that there are going to be a lot of moments in the immediate future where people will be looking for answers.

JW: We’re conditioned to think about productivity and capitalism, so art has to be a product that gets bought and sold that is the thing, you know where you can only measure the impact with your certain metrics. But what if the way we measured art wasn’t always about impact? Art really does have the potential to do something, to be an action not a product.

Christina Battle, Today in the news more black and brown bodies traumatized the soil is toxic the air is poison (2018). Collage installed on bilboards for The Work of Wind: Air, Land, Sea exhibition, Blackwood Gallery, 2018. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid.

CB: It might be overly optimistic, but I think it’s better than just giving in to it. I mean, people need to know that there are communities of people who have been persecuted and oppressed for generations, and still haven’t given up. There’s something to be said about being resilient and resisting and keeping going. This idea of hopelessness is just such a Western idea. The idea of giving up. Like, what, you’re just going to give up? That’s ridiculous to me. To me, that’s why conversation is so important. It’s one of the things we all have in common, communicating with one another, however that is done. I really feel that, and I think that’s one of the things that art does well: it starts conversations.

NOTES

- As an aside, the Chuckegg Creek Wildfire, which started in May, 2019, was finally contained in late August 2019, three months after we first started this conversation. While it has been listed as under control, crews are still conducting scanning operations to identify hot spots. The wildfire resulted in the evacuations and the loss of homes—especially in the many First Nations communities in the area.