Francisco-Fernando Granados

WE IMMIGRANTS, WE REFUGEES,

WE CITIZENS, WE SETTLERS

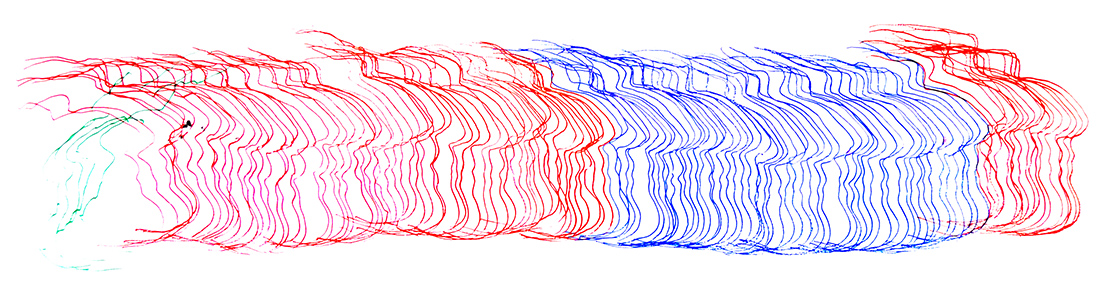

Francisco-Fernando Granados, spatial profiling (After Margaret Dragu’s Eine Kleine Nacht Radio) (2013). Performance and site-specific drawing, dimensions variable. Performed for Mayworks, Festival of Working People and Arts in Toronto. Photo by Manolo Lugo.

Those few refugees who insist upon telling the truth, even to the point of “indecency,” get in exchange for their unpopularity one priceless advantage: history is no longer a closed book to them and politics is no longer the privilege of the Gentiles.

—Hannah Arendt, We Refugees1

SETTLERS IN OCCUPIED INDIGENOUS TERRITORIES have an ethical and political obligation to hold up our end of the nation-to-nation dialogue. On the part of Indigenous nations, the Idle No More Movement has highlighted the political will, creative vitality, and generous readiness for this dialogue. The energy expressed through the cultural and political manifestations of the movement is an inspiring exhortation to non-Indigenous people in Canada. It issues us the honourable challenge of correcting history by meeting First Nations in full recognition of their sovereignty to have a conversation as equals. In order to participate in this process, those of us with access to citizenship rights need to claim this dialogue on behalf of Canada. This is not a call for a generalized approach to decolonization or an appeal for reformist adherence to the nation-state.2 It is a serious proposition for an affirmative sabotage3 of citizenship and its political potential at its most fragile moment.

We must make use of the public agency still available to citizens now that the international fantasy of Canada as a benevolent liberal haven is evaporating under the harshness of laws like Bill C-514 and Bill C-245. Bill C-51 has granted the federal government unprecedented powers of surveillance, prompting the United Nations Human Rights Committee to raise concerns over the potential for human rights abuses.6 Bill C-24 has created a hierarchy of belonging that makes it possible for Canadians of immigrant and refugee background to have our citizenship revoked. Columnist Stephen Marche laments these recent developments as “the closing of the Canadian mind.”7 When has the Canadian mind been open to dialogue with Indigenous nations in equal terms? The erosion of rights to privacy and citizenship, to freedom of expression and freedom of thought enacted by these laws does not signal the end of a golden era of liberty and security protected by the kindness of the federal government. These and other measures taken by the Harper Government should remind non-Indigenous Canadians of all of the rights that were taken away from Indigenous people through laws like The Indian Act and the institution of residential schools. Francisco-Fernando Granados, spatial profiling (After Margaret Dragu’s Eine Kleine Nacht Radio) (2013). Performance and site-specific drawing, dimensions variable. Performed for Mayworks, Festival of Working People and Arts in Toronto. Photo by Manolo Lugo.

It is with an awareness of history and the present situation that the self-interest of the Canadian citizen must be opened up in the direction of the nation-to-nation dialogue. Political analyst Stephanie Irlbacher-Fox addresses the limits of settler solidarity by expressing scepticism “about the willingness of settlers to support a movement in a sustained way on the basis of either moral responsibility or self-interest.”8 I agree that sustained involve- ment requires settlers to “engage in personal transformation to entrench meaningful decolonization,” and that this transformation begins with the education of the young.9 This point echoes Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s ideas on aesthetic education. She proposes affirmative sabotage as the “productive undoing” of the legacy of the European Enlightenment by claiming it as a tool and learning to use it in order to carefully undo the legacy of European colonialism.10 I propose that the personal transformation of settlers and our sustained engagement as allies to Indigenous people within the political process requires a productive undoing of the privileges of citizenship. The position of the settler needs to be occupied and activated, if we take our cue from the social movement for economic justice.

The affirmative sabotage of the position of the settler will require deep transformation in the hearts and minds of non-Indigenous Canadians. Speaking from the colonial end of the conversation requires settlers to identify with the ongoing history of illegalities and genocidal violence the federal government has institutionalized against First Nations, Métis, and Inuit populations. This identification must certainly include the white settler populations that have inherited the resources of British and French colonialism. These communities have the benefited the longest from the economic, social, and cultural privileges that were set up at the expense of Indigenous nations, and they need to hold themselves accountable.

As a racialized first generation Canadian, I am focused here on accountability as it continues past the edges of whiteness. It must include Canadians of racialized immigrant and refugee backgrounds who also benefit from the privileges of colonial oppression, even if not in the same ways and to the extent that white populations do. Stepping up to represent the colonizing power in this conversation might seem like a counter-intuitive move, particularly for settler-citizens who have been affected by racist and anti-migration policies and attitudes, or who have a range of complex relationships to Indigeneity in the places we come from.

Many people in immigrant and refugee communities belong to Indigenous groups in their countries of origin; for some of us, the brutality of colonial violence in the places we were born has made it impossible to learn about the Indigenous roots of our mixed blood. Many of us have survived dehumanizing processes to be able to stay in this country. We have witnessed friends and loved ones deported and kept from entering the territory. We have seen our family’s and even our own mental health crumble into addiction, depression, mania, and suicide. It is in honour of this grief that we must own the position of settler. This could be a path to the healing we so desperately crave.

Claiming a space in a dialogue with Indigenous people in Canada has to move along with difficult conversations within our own communities. It should acknowledge the ways in which class formation overlaps with race to create vastly uneven levels of economic privilege and disenfranchisement among immigrants and refugees, and how this affects the ways in which people can participate in the dialogue. Double bind: how to harness the power of collectivity while understanding and trying to work against the inequalities that challenge the unity of categories like “newcomer” and “people of colour.”

This double bind generates problematic politics of representation. At its most seemingly benevolent, it promotes crass tokenism within institutions, conservative and otherwise. What kind of progressive non-profit do we have when a manager takes a youth intern to a policy meeting without explaining where they are going or why they are there, only to make sure that it is noted in the minutes that there was a representative “from the refugee community” in the room? This is not the kind of representation needed for the nation-to- nation dialogue. As Angela Davis notes, “there are no compelling arguments to be made about political progress” when “notions of multiculturalism rely on a construction of race and gender assimilation that leave existing structures intact.”11

The other problematic that can carry over from movements asserting the rights of immigrants and refugees in Canada towards the nation-to-nation conversation is a tendency towards the kind of radical posturing that breeds nothing but self-interested cults of personality. Radical posturing does not by itself equal lasting structural change. Those of us from racialized migrant groups who may have the resources to work towards a nation-to nation dialogue should aim to remain self-aware and self-critical. Self-aware of how our own culture, race, and class background positions us in relationship to a colonial dynamic not only in Canada, but also in the places that we come from. Self-critical of the ways in which our bodies are included when discussing the Canadian political landscape, and of the ways in which tokenized individuals are encouraged to cultivate narcissistic personalities by those in power who care more about optics than substance.

Stepping up to the dialogue on behalf of Canada does not deny the realities of racism or undermine the solidarity of settled migrants. Affirmatively sabotaging the position of the settler is a question of working within the scope of this particular colonial situation and recognizing the specificity of the nations that are occupied under the Crown.

It is a painful and shame-filled move for those of us who reject the brutal circumstances that founded and continue to shape the country. It requires re-imagining our means of criticizing, opposing, and demanding change in the government’s colonial behaviour: from a position of outsiders towards a fiercely constructive auto-critique. It is not a call for assimilation. It is a strategic shift that must compliment a range of strategies in the struggle against the hierarchies derived from white-supremacist, patriarchal, colonial domination. Assuming the Canadian side of nation-to-nation dialogue must become continuous with the struggle against anti-Black racism and police brutality, deportations and the closing of borders, transphobia and homophobia, sexism and rape culture, and ableism.

For settlers who have a level of awareness of our complicity in the colonial process, the road towards the Nation-to-Nation dialogue includes the task of consciousness-raising among the collectives we feel as our own. This task must exceed solidarity and move non- Indigenous communities towards a will to use whatever institutional agency we might have available to us in order to hold Canada accountable. Immigrants and refugees who have eventually become citizens are aware of the highly constructed protocols of the process of coming into being as citizen. Working towards the creation of a desire and determination for the Nation-to-Nation dialogue becomes especially urgent as immigrant and refugee populations become instruments in the service of socially conservative political agendas. Can racialized bodies be made visible in the national political landscape beyond practices of tokenism within political parties? Are the voices of immigrant communities listened to unless they serve as alibies for international military intervention in places like Syria and Iraq,12 or to be paraded out en-masse during demonstrations defending backwards causes like the campaign against the Ontario Sex Ed curriculum?13 Is it possible to have refugee protection issues gain attention from governments without having to go viral like whatever banal meme or pet video bracketing these posts on social media? Are we capable of understanding that the notoriety the semblance of a precious child can gain in death is not the same as the dignity and protection he should have been granted in life?14

We need to give weight and build on the sentiments voiced by Immigrants In Support of Idle No More, who declare:

As racialized migrants, immigrants, and refugees, we express our support for the Idle No More movement, a movement of Indigenous surgence/resurgence across these lands. We are allies of Indigenous peoples’ asserting their rights and sovereignty and protecting the lands and waters. The history and current reality of Canada is a racist and genocidal one, marked by the forced dispossession of Indigenous peoples’ lands and extraction of their resources, the suppression of Indigenous customs, governance, and laws, and the attempted assimilation of diverse Indigenous cultures and identities.

As racialized migrants and refugees, we came across many oceans or continents, a hundred years ago or yesterday and are being targeted by racist and exclusionary immigration policies. Enduring decades, if not centuries, of colonialism, empire, racism, impoverishment, violence, and displacement; paying a Head-Tax, growing up in internment camps, living in constant fear of deportation and denied access to basic services, unable to be reunited with our family members, working long hours for less than minimum wage in dangerous industries/sweatshops; deemed “illegal,” “undesirable,” or “terrorist” by the Canadian government (and often Canadians), many of us have struggled to find stability and to make homes here on Turtle Island. But we recognize that our homes are built on the ruins of others. We are on the lands of Indigenous peoples: lands unjustly seized, unceded lands, treaty territories.

With humility and gratitude, we affirm our solidarity and support for the sovereignty not of the illegal Canadian government or its immoral laws but of those communities whose lands we reside on.15

The awareness of our complicity certainly begins with the acknowledgement that “our homes are built on the ruins of others.” With the humility and gratitude with which we affirm our solidarity and support, we must also recognize that the illegal government and its immoral laws are the ones that govern us. How many of those of us who managed to stay swore allegiance to the Crown at a citizenship ceremony? Whether we liked it or not, whether we did it under family coercion, out of naïve idealism, or with absolute indifference, this is our claim to the disappearing public sphere. This is our claim to the abstract structure of the state. This is the nation Idle No More asked to be in dialogue with.

Precisely because the public sphere and its civil guarantees are in danger of being taken away, the politics of owning our deeply problematic settler-citizenship needs to be argued as reasonable. There is nothing radical about owning our shit. Indeed, this kind of reasonableness is the honourable response to the call for dialogue, the attitude that can lead us in good faith to a Nation-to-Nation discussion. The broad vision for this negotiation should entail a redistribution of resources and the healing of relationships with Indigenous communities, while safeguarding our shared ecosystems.

Colonial cruelty engineered the process of settlement as a means to create loyalty for the occupation. It is cruel not only because it divides communities that should be allies, but also because the feeling of being settled is the most needed relief for the refugee. As a teenager coming to Canada during the transition between the end of the Liberal and the beginning of the Conservative era of the early 2000s, settlement was the goal, the main aspiration of a new life. At home, it was the dream of leaving behind the trauma of the place of our birth and the hope of an arrival to a safe space. Settlement was the implied directive to “adapt to Canadian society” by going to school and volunteering. It was “Settlement Services”16 which gave me access to public libraries, art programs in community centres, and the hope of higher education. Settlement was also the joy of finding a peer group of other immigrant and refugee youth who understood my experience. It was the possibility of discovering and exploring my queerness. For the refugee, settlement is a double bind.

As I went on to become an artist, I was fortunate to learn from women who are artists and curators what laid beyond the colonial horizons of my formal education. Rebecca Belmore taught me the name of the disappeared;17 Cheryl L’Hirondelle taught me the names of the land; Merritt Johnson taught me cross-border solidarity; Skeena Reece taught me about humour as a political tool;18 Wanda Nanibush taught me the term “settler accountability;” Daina Warren gave me a space to begin to write.

Originally published as part of voz-à-voz, e-fagia visual and media art organization, Toronto, 2015 http://www.vozavoz.ca/

NOTES

- 1 Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees,” in Altogether Elsewhere: Writers on Exile, ed. Marc Robinson (Boston and London: Faber and Faber.

- 2 “Gayatri Spivak: The General Strike Is Not Reformist,” The Nation (April 27, 2012). https://youtu.be/GHfRq1ydFCw

- 3 “Gayatri Spivak on An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization,” Harvard University Press (January 20, 2012). https://youtu.be/YBzCwzvudv0

- 4 “Bill C-51,” 12 September 2015, https://openparliament.ca/bills/41-2/C-51/.

- 5 “Bill C-42,” 12 September 2015, https://openparliament.ca/bills/41-2/C-24/.

- 6 Stephanie Levitz, “Bill C-51 not in keeping with Canada’s international obligations: UN,” The Globe and Mail (July 23, 2015) http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/bill-c-51-not-in-keeping-with-canadas-international-obligations-un/article25642360/

- 7 Stephen Marche, “The Closing of the Canadian Mind,” The New York Times (August 14, 2015). http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/opinion/sunday/the-closing-of-the-canadian-mind.html

- 8 Stephanie Irlbacher-Fox, “#IdleNoMore: Settler Responsibility for Relationship,” 12 September 2015, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, https://decolonization.wordpress.com/2012/12/27/idlenomore-settler-responsibility-for-relationship/.

- 9 Ibid.

- 10 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 1.

- 11 Angela Y. Davis, The Meaning of Freedom and Other Dialogues (San Francisco: City Lights Publishers, 2006), 88.

- 12 The Canadian Press, “Stephen Harper slams Liberal, NDP ISIL strategy as ‘dropping aid on dead people,’”

- 12 September 2015, The National Post, http://news.nationalpost.com/news/canada/canadian-politics/rivals-isil-stance-like-dropping-aid-on-dead-people-harper.

- 13 Robin Levinson King, “Fact-checking 10 claims made by parents against the Ontario sex-ed curriculum,” 12 September 2015, Toronto Star, http://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2015/05/04/fact-checking-10-claims-made-by-parents-against-the-ontario-sex-ed-curriculum.html.

- 14 I can’t bear to cite this. I refuse to link someone to an article that will inevitably have the image. *Editor’s note: In its original context, this comment referred to viral images of the body of three-year-old Syrian boy Alan Kurdî, who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea 2 September 2015.

- 15 “Immigrants In Support of Idle No More” 12 September 2015, http://www.idlenomore.ca/immigrants_in_support_of_idle_no_more.

- 16 “ISSofBC / Settlement Services,” 12 September 2015, http://issbc.org/prim-nav/programs/Settlement-Services.

- 17 “Rebecca Belmore / Vigil,” 12 September 2015, http://www.rebeccabelmore.com/video/Vigil.html.

- 18 Francisco-Fernando Granados, “Epic Houses: The Auntie-Hero Performances,” LIVE Biennale, 12 September 2015, http://livebiennale.blogspot.ca/2008/12/epic-houses-auntie-hero-performances.html.