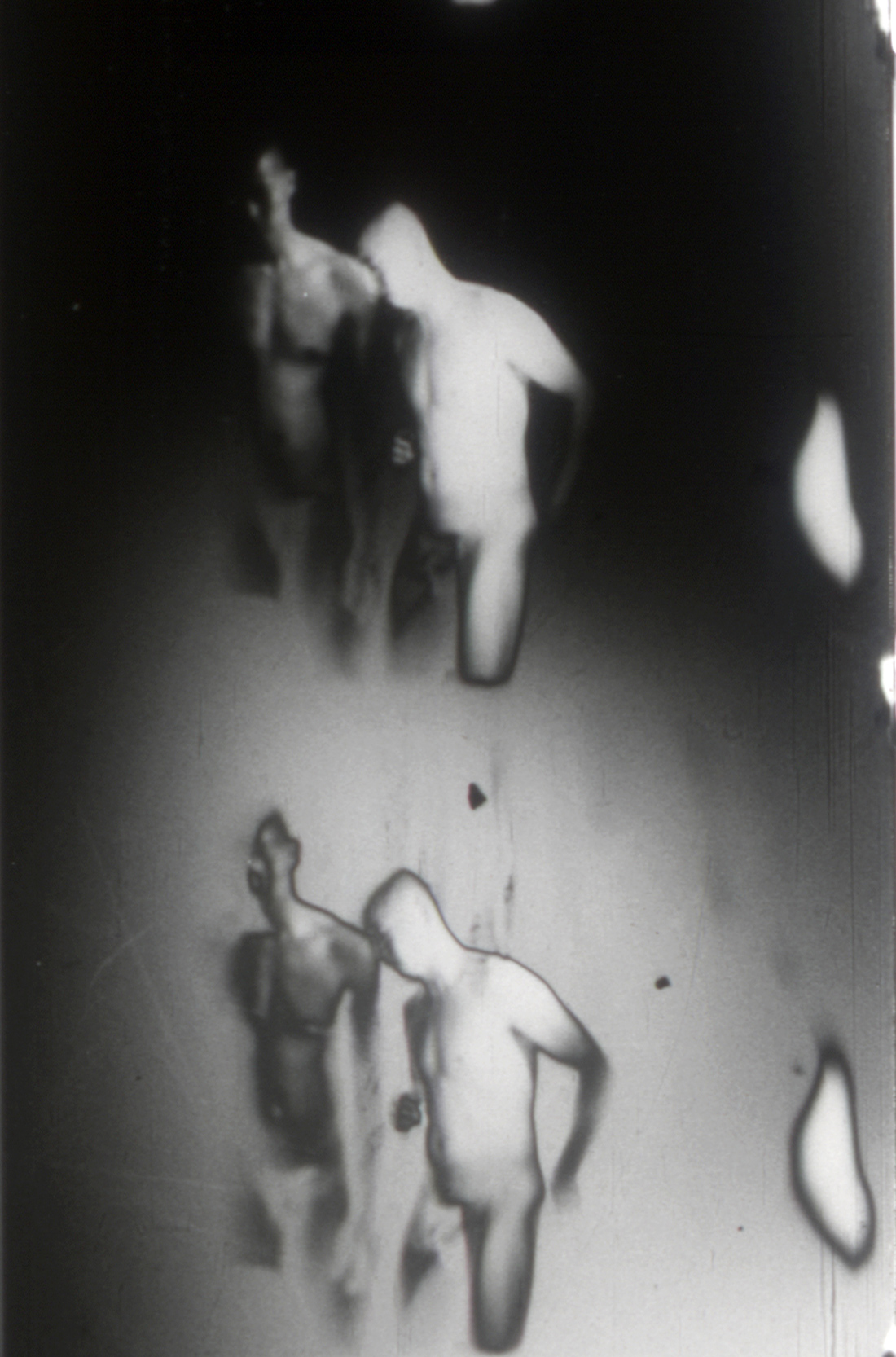

Chris Chong Chan Fui, Minus (1999). 16mm, 3:00 minutes. Courtesy of CFMDC.

Scott Miller Berry

QUEERNESS MIGHT HAVE DECEIVED US

AN INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS CHONG CHAN FUI

Scott Miller Berry: Hi Chris! Let’s start with you sharing an early formative memory of something artistic.

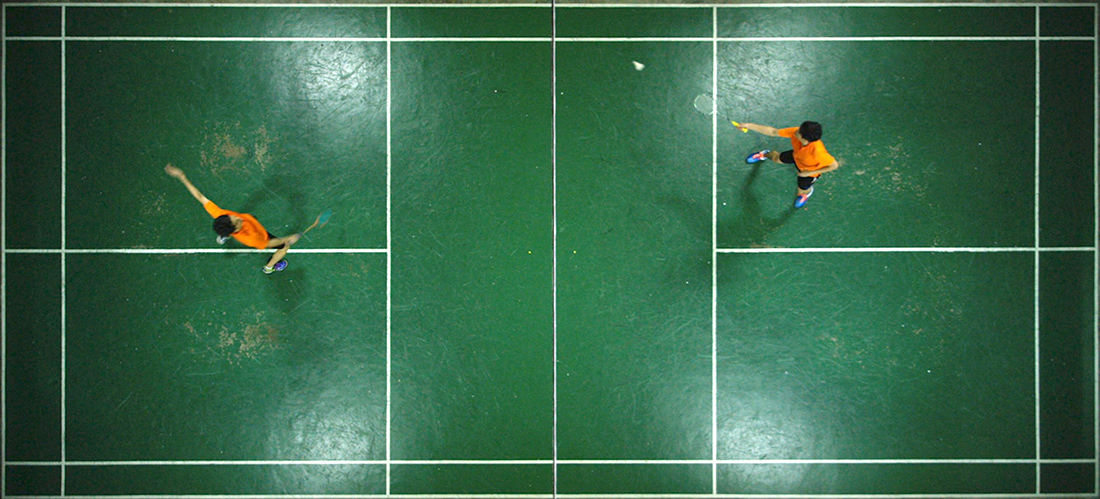

Chris Chong Chan Fui: I remember art class. A distinct painting when I was 13 or 14. I was already intrigued by Issey Miyake at that age and I didn’t know why. Nothing in my surroundings were urban or worldly in anyway, I’d never been exposed to high fashion so why was I so interested in some obscure Japanese avant-garde designer in the 1980s? At the same time, I was also quite immersed in sports from a very young age. Any after-school activities were strictly involved in at least two to three hours of sports and the sport would vary depending on the season of the year. From badminton, to running, to basketball—it was nonstop. My sisters were quite creative, being involved in piano, dance and photography. I remember my youngest sister’s interest in photography. I remember not caring about the pictures, per se, but with the machinery of the camera. The shape, the metal, textured leather, the clicking and winding noises. There was a real presence of the camera as an object, something physical held on your body. It’s funny that I don’t remember the photos she took nor did I care about the subject matter. I think I feel the same way about film today and about the insignificance of people being present in the image. My family was indifferent to art making. It wasn’t a part of the conversation. Nothing much was shared around our family table. Our family was like a ship, broken in two, but still floating around as if it were one. Neither good nor bad, but the role of art or any sort of alternative thinking didn’t start from family.

SMB: What inspired you to pick up a camera and make your first movie, Crash Skid Love in 1998?

CCCF: A few things led up to making my first film Crash Skid Love. Actually three. Funny how this first film was claymation of all things. I never had any real training in filmmaking, let alone animation. Animation was nearest to photography and the building blocks of making images move, so I thought to myself it was part and parcel of learning the process. Let me also add at this point that I never had any interests in making a drama, being part of Hollywood, or finding the need to discover or document new cultures. My point was purely based on technical curiosity without the thought of where I stood in it. Living in Toronto with its access to Cinematheque Ontario, which I took full advantage of every week, I knew an interest in cinema was there and it was personal. Personal because I didn’t feel the need to share how I felt about the films I saw. At the same time, there weren’t many people in the theatre to share it with anyway. The films and the theatre became my social surroundings. My relationship with these films linked me together with life outside the theatre. So, the Cinematheque was my first inspiration. The second was artist and software engineer Nicole Chung. Our friendship, our Asian-ness, put us together. I wanted to be more rebellious but didn’t have the courage to be so, but she was. I learned that it was okay to be proud to be Chinese and to be yellow when I was with her, and most importantly, to be a Chinese person who made mistakes and did stupid things. To be an activist but still fall off the imperial high ground once in a while. I didn’t meet anyone else like her at that time, and haven’t, even to this day. She was constantly on the outside, and I would find myself outside with her. We both didn’t belong. This is where inspiration number three comes in through artist Allyson Mitchell and her queer youth project. I was thinking about why “queer youth” drew my attention. I was queer. I was a youth. But If you asked me to join something queer, or something youthful, I would suddenly feel I was attending another all-white event. But when Allyson had this program for queer youth in Toronto’s Chinatown, for some reason, it felt like she was talking to me. Or, maybe it was because it was happening on the same street I was living on. Who knows. But, I did feel like it was mine.

So, Crash Skid Love used clay because I didn’t know I needed to deal with people. I knew that 24 frames made a second and I knew I had to light the shit out of it so I bought two powerful portable car lights and pointed it at my Ikea pine square dinner table. My animation set on the table looked like a ten year olds’ science fair project with the exception of a leather man and his swinging gender. The story was juvenile and stereotypical, a raver’s crush on a punk, but in hindsight, it was a true reflection of how I was seeing the Toronto scene at that time with everyone in their own gangs and uniforms. I think I was a poser, a crossover between skater and raver, if there even was such a thing. So, that was Crash Skid Love. I didn’t enjoy any of the traditional processes of making a film like dialogue, continuity, set design, etc., but what I did come away with was the beginning of a love affair with light and motion!

SMB: How did you find your way to Film Farm [Independent Imaging Retreat] in Mount Forest, Ontario in 1999?

CCCF: I’m not particularly sure of how I became linked to Phil’s (Hoffman, filmmaker and co-founder of Film Farm) community. I wonder if it was Jai Sarin, who I was friends with together with Nicole Chung. I didn’t know what to expect, but what I did want to know was the bare bones of a motion picture camera without added functionalities of post-production. I just wanted to know about the machine itself. There was no pretension at Film Farm. I felt the weight of Phil’s personal losses during my stay. I respected it. I was there to work between the space of movement and exposure, in that specific order. Movement: With the Bolex camera, I wanted to immediately mask and cover the lens in the attempt to isolate the movement, then shoot it. Then, I wanted to go to step two in the darkroom where I would expose it in a different way. Funny how I was thinking of exposure in the darkroom and not the actual exposure of the film during the shoot. But yes, movement then exposure.

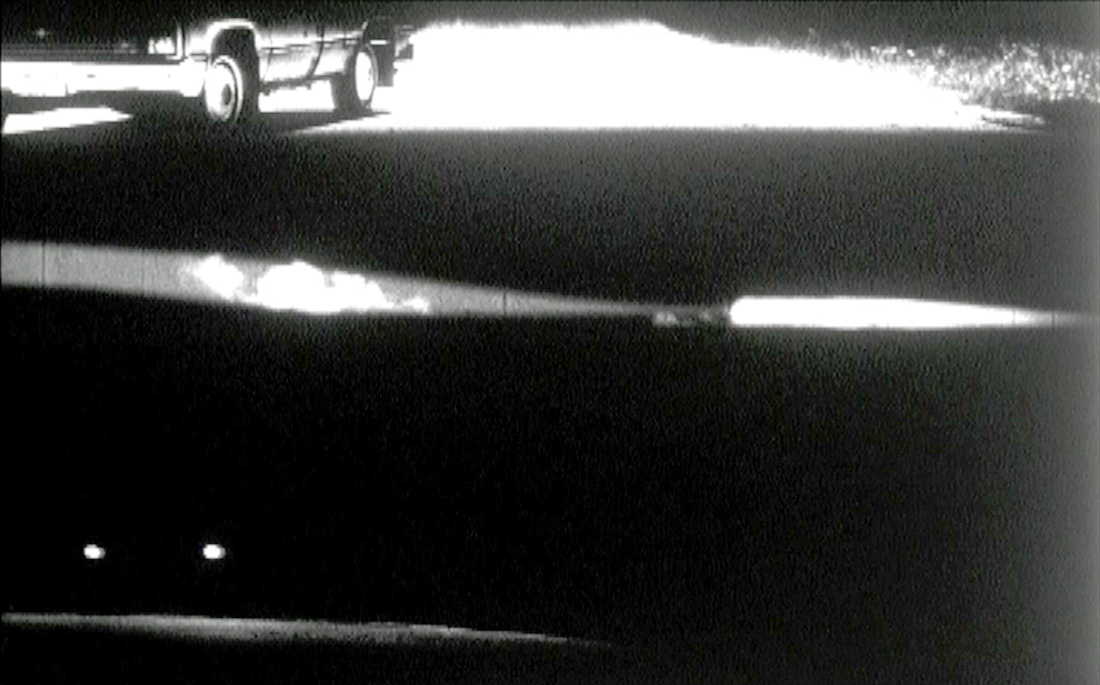

Chris Chong Chan Fui, Karaoke (2009). HD / 35mm, 75:00 minutes. Courtesy of CFMDC.

SMB: After making Minus (1999) at Film Farm, you went on to make six short films/videos. Then in 2008, you made a feature film, Karaoke (2009), and have since moved into the territory of gallery exhibitions with installations, interactive works, illustration, and photography. What do you miss—if anything—about working with “artist filmmaking” approaches? And, would you make a feature film again?

CCCF: I miss the craftiness of celluloid. Celluloid can be manipulated, just like paper. I think that’s why I wanted to start painting in translucency with layering inks. It is a similar process to layering images and tones onto a film negative.

A feature film is a commercial venture. I was naïve of this and it broke me. I was naïve of the fact that my film needed to sell or become popular, or it needed to be admired by art house power brokers in the European/North American art-house circuits. None of this was on my mind when I made the film and I didn’t pursue it as such, which was my mistake. I knew that if I wanted to continue and make another feature film or be a feature film director, I would need to make these criteria of popularity and admiration my priority. But, like when I was a teenager, I didn’t see it. It wasn’t the golden goblet. But when I saw Minus being projected for the first time at Phil’s farm, THERE was my prize! And again, only three people were in the barn, at that time, watching the film with me. Funny how the most monumental times in my life are witnessed by just two or three people. These moments are sporadic and uncontrollable. Another feature film could be in my future if the pieces and

Chris Chong Chan Fui, Music Might Have Deceived Us (2000), 16mm, 6:00 minutes. Courtesy of CFMDC.

the people are right. But, I don’t believe that a long-form film should be a defining part of one’s artistic repertoire.

SMB: You mentioned that Film Farm wasn’t institutional, do you think the Canadian artist run centre ecology is institutional? How would you compare that to the institutions you find yourself working with now?

CCCF: The Farm takes place in someone’s home—Phil’s home. It’s a personal space you’re invited into. It’s something familial and even parental. I felt that since everyone was a beginner and the practice of hand-processing is about the “beginning” steps of how images move, it was easy for everyone to drop all their pretensions and become a child again. There was nothing to gain from knowing anything about film because hand-processing was a purely instinctual methodology, and the easiest way to manipulate it was to surrender to it.

The nature of an artist run centre is highly organizational. A clear division of labour. You do this; I’ll do that. We all receive financial compensation to live on. This is an efficient model as long as money is involved. Within an artist run centre, like any institution, there are mandates. A coherence to conform to a series of set activities or guidelines of who you are as an entity. There is a vision at stake. There is an audience at stake. There are funders/investors at stake. There is your rent money at stake. There is something at stake when the value of your contribution has been monetized.

There is nothing at stake at Phil’s farm.

Artists desire power. The power to exert an idea. An artist run centre is initiated by this power. The multiple levels of an artist run “organization” requires there to be a division ofthis power which I believe further dilutes the intention of the initial idea of an artist run centre. Does everyone in the division believe in the power? If not, then it’s an institution. If everyone does, then it becomes a “Film Farm”. Or, a sexy commune!

Currently, I’m working predominantly with museums, galleries, and in special exhibitions. Most are not artist run, but artists are sometimes playing double duty as both art producer and gallerist / exhibitor. So, they too, become artist run in a broad and generic sense. I find the institutions I’m working with now, and the institutions I worked with before, to be quite similar because both have something to prove. Again, I want to bring back the term “mandate”. This is the ego of the institution that needs to be defended, and the people who work within these institutions, whether it be artist run centres or galleries/ museums/exhibitions, always have a mandate to achieve, and their own ego to protect. Let me clarify that a bit: mandates are not only about just the goals of the organization, but also the ambition of the people within them. For example, if the institutions’ mandate is about presenting art that relates to trees, then they have to show something expressing trees. But, it doesn’t stop there, the people within this organization have their own vision of a tree and also have something to prove. So, the ego of both the institution and the personnel must be fulfilled. The mandates must be fulfilled.

SMB: Can you talk a bit about your transition from short films to feature film to the gallery world? What are the advantages and disadvantages of working in commercial visual art ecosystems at this time?

CCCF: Film festivals for short and feature films were quite confusing for me. The communities seemed to have different ambitions that were forced together, and the filmmakers were left on their own to figure it out. Shorts were supposedly a stepping stone to features, and features were supposedly a stepping stone to greater profitability. I never saw it this way. I never had a goal when I started playing with film. It was never about ambition. The film community, all of a sudden, seemed so small. I didn’t want to step in any further, but at this time during the late 1990s, the term “moving image” came out and different institutions such as museums and galleries started becoming a new exhibition space for alternative film.

Being involved with the gallery and museum world was more immense. Overwhelmingly so, but that immensity also meant I was able to be lost in it. This immensity was comfortable for me because, again, there was no ambition to be had, because the art industry looked unsustainable to me, just like the film industry, but on a much larger scale. This was relaxing, oddly enough, because I had no financial stake in it. No expectations and no financial goals. I liked hovering underneath it all. I believe this lack of financial direction allowed me to experiment and continue to ask questions contrary to trends.

My short films were divided into two sections: Phil’s hand-processed Film Farm films, some of which have still yet to be completed, and the shorts I made in Southeast Asia. I don’t treat the hand-processed films the same as the shorts I did in Southeast Asia because, as you know, the hand-processing is a different body of production altogether. It’s a different machine altogether. The shorts I did in Southeast Asia were made digitally simply because I didn’t have access to celluloid or its chemicals. I brought my Bolex to Malaysia in the hopes of continuing processing but access was almost impossible. I didn’t like the digital camera and I still use it begrudgingly. I wasn’t completely happy with my shorts in the digital format. They just seemed so thin; they had no body. I was forced to think in the convention of storytelling which seemed so contrived, and in the regional context, it became hyper exoticized. Imagine working on a medium like celluloid and having the ability to change its form, colour and composition, and all of a sudden, you have to move to a digital format that you cannot touch nor feel and yet you’re suppose to pull something emotional from it? It was like pulling feelings from an Etch A Sketch. I still feel the same way to this day.

At the time, visual artists and their respective curators and academics were not familiar with the moving image. The term “film programmer” and “visual arts curator” were two separate species. So, the curators just ignored us, which I believe became an advantage. We were invisible and irrelevant at the time. I don’t think that any of us working in experimental film were in it to gain respect. We were just romantics and we didn’t care, since we didn’t need any approvals. Not being in the conversation allowed for the moving image artists to grow at our own speed.

Additionally, the exposure for the moving image artists in the space of the visual arts during the early 1990s and 2000s was burgeoning. Experimental film used the museum and gallery space differently. It was a new chew toy for the visual arts industry, an industry that always looked to reinvent itself. A cinema was always a cinema: a screen with an audience in front. Visual art spaces could reimagine their spaces with respect to scale and light. Although respect for the grain or quality of the image was always an afterthought at the time, both moving image artists and visual arts exhibitors were still excited to play with the museum and gallery spaces.

A final advantage for moving image artists working in a visual arts context is a purely selfish one. It is the ability to watch the work over and over again, on repeat. The matter of time becomes a little bit cheated because we lose the importance of seeing it in the moment, only once. Seeing it only once allows our memory to digest it and remember it in different ways. But at the same time, revisiting a moving, time-based image over and over again, brings about analysis and comparison. The comparison to a painting is apt, but a painting was never time based. So, perhaps a better comparison would be watching a factory worker on an assembly line doing the same thing, over and over again, day after day. The actions are the same, but perhaps our interpretation evolves.

Although the largely untapped landscape of the visual arts world could seem enticing for the moving-image artist, the disadvantages are a plenty. First off, setting up a film shoot is expensive; it’s more expensive than your average painting or sculpture. Using found footage is often the cheapest, other than the cost of copyright fees. Hand-processed cameraless filmmaking is also an affordable and beautiful technique as well. But, as soon as you require a setup of lights, actors, and movement, the costs balloon out of control. I found that the visual arts world at the time didn’t understand this. The fees were the same, and the discourse was irrelevant. I believe that the process of shooting, however big or small plays an important part in moving-image art. It is not a documentary. It is articulated and purposeful. Just like picking a brush or creating your own inks. I believe that the visual arts world wasn’t educated on the history of cinema and so they weren’t able to see the importance of it. So instead, they used their own vernacular—a language that was too heavily set on the background of the artist rather than the impression of the flickering lights ahead.

Chris Chong Chan Fui, Block B (2008). 35mm, 20:00 minutes. Courtesy of CFMDC.

Another disadvantage would be the lack of community. When I stepped out of the independent festival and experimental film communities, the circle disappeared. I didn’t feel a part of either the film community or the fine arts community. There were other moving-image artists but they were few and far between.

SMB: What would you change about the state of the so-called “art world”?

CCCF: People who are in it for the money should not deal with artists, period. That means conventional gallerists, publishers, producers, collectors, dealers, nonprofits, and private/ public institutions—anyone who “monetizes” an artist. To monetize means that our expressions must be dwindled down to monetizable units, something divisible. Something divided into recognizable and familiar pieces. An understandable unit of thought. With these pieces, we will have a foundation where we can start building and growing. You can’t build something without a solid foundation, right? This, I believe, is the mistake. We forget that risk and divisiveness within the cracks is where the real growth happens. This is where art stretches out in new awkward directions to find new instabilities. But this takes risk, and unpredictable risk scares conventionality and its stakeholders.

So who should deal with artists? An artist, whether they be literary, performative, media, or object oriented, requires a buffer from the external voices of today’s short-sighted economic forces. If this buffer of cultivators doesn’t exist, the artist is constantly fighting with themselves and the world as a whole. There is no freedom in this manner. Fuck those people who say

Chris Chong Chan Fui, Badminton Training (2015). Three-channel video installation & live performance, Dimensions/duration variable. Courtesy of CFMDC.

that artists make the greatest work when they suffer. That’s idiotic and patronizing. I believe that we need someone similar to a curator/programmer but without the power to create exhibitions/programs. It should be someone who has no financial or personal stake. A new profession of cultivators, not curators. Prophets, not programmers. The cultivators’ role is to ensure artists are treated humanely with the basic standards of living, provided with creative guidance that’s both emotional and professionally productive, and finally, to secure the dissemination of tools and materials for artists to work with freely. With the support of cultivators, the role of an artist can become the priority of the artist! Fancy that! There is no art where there is no risk, and there is no risk when there is a reward. A cultivator who deals with artists directly should look at an artists’ work as an infinite, unrelenting flurry, rather than a finite all-encompassing logline.

SMB: What was exciting about being part of an artist film/video “scene” in the early 2000’s? Did that have anything to do with artist run centres themselves or simply the people around you? Do you have anything to say about the “abundance” of artist run centres and funding in Canada and the very different cultural landscapes in Malaysia?

CCCF: My social circles were mostly in the experimental film or visual arts communities, but oddly enough, I never saw them as that. I saw them as friends, never really thinking of them in the context of the arts. I had no ambition with film, nor with the visual arts at that time, so I never saw the ambition in others, just a spirit of excitement of seeing new and provocative experiences. The artists were part of the social environment, so it never really stood out for me. To put it in a geographical context, I was living on Spadina and Queen West in the late 1990s, so there weren’t any financially successful artists / filmmakers within my circles. I wonder why? Why didn’t I have a gauge of artistic success? Probably because I didn’t know what success meant in the film and visual arts communities. At that time, I remember that getting a film into Wavelengths [at the Toronto International Film Festival] felt so unreachable, but it didn’t matter because that was never a goal. My goal was to learn and to be curious. It was never about exhibition. I worked in an office during the day and I played with 35mm and Super 8 film in my bathroom at night. Definitely the people were exciting. The individual artists who floated in and out of the film/video and arts scenes were the most exciting to me. Artists Nicole Chung and Allyson Mitchell, or cinematographer Tan Teck Zee were the most meaningful for me. You were either in the scene or you were watching it happen in front of you. I was one of the latter, but that was fine! There was less pressure to engage. I didn’t even realize I was thinking only of people and not organized groups or institutions (ARCs, galleries, museums, festivals, events, et al). It’s quite telling. Although groups were a plenty in Toronto, they still required access (people who knew people in order to enter the scene) and money (paid exhibitions, workshops etc.) for artists to participate. But, I still didn’t know what I wanted out of film or the arts, so these were not the first places I would think of going. In hindsight, this, too, was also very telling. Sometimes, I wasn’t even sure what resources these groups provided. Were these groups created just so they could have paid employment for the people organizing them? Either way, even though there were many groups in the city, it was still difficult to find support and direction as an artist. Shouldn’t outreach to artists be the number one priority? A dance company should reach out to an audience of dancers first. A film festival should reach out to filmmakers first. A gallery/museum should reach out to artists first. The lack of outreach and exclusionary practices of supposedly creative groups towards artists is always a telling sign for me that the organizations’ intentions are not about supporting artists. These faux creative groups are meant to support audiences and other stakeholders/investors, which is fantastic, but let’s call a spade a spade. Paying artists to perform should not be the primary strategy of supporting an artists. We are not performing monkeys. Support should be multifaceted and should cover the entire scope of art production. After discovering this illusion, creative organizations, big or small, were, for me (and don’t forget I was a business school graduate), no different than Procter and Gamble selling consumer products like soaps. There was no distinction in my eyes. Groups may have a facade of support for the arts, but just under the skin lies a mandate that is more about organizational sustainability. This is exactly the same as in most of the organizations I’ve encountered in Asia as well, although Southeast Asia is still going through its own growing pains, but I’m hopeful since there is still no value in the arts in the region which means that arts production is solely for the expressions themselves.

Perhaps what I’m trying to get at is a longing for more collective ways of organizing. I think we do need more collectives and alternative organizing principles, but I also think overall institutional structures and systems need to change. How can we shift power back into to artists?

SMB: This book is centred on Indigenous/ racialized/ LGBTQ/ differently-abled media arts practitioners and aims to fill a massive gap. I’d love to know your thoughts about being a queer artist of colour and how those realities have impacted you in your career to date.

CCCF: A complicated question considering I’ve lived both in Canada and Malaysia in significant ways now. Both countries have such opposing treatments of race, gender, and queerness. They also have opposing ways of treating arts and culture.

The thing is, in order to start thinking of myself as a practitioner, I felt I had to think of myself as being of colour. Then after that, think of myself as being queer. I became more aware of my yellowness amongst non-yellow company, and more aware of my queerness amongst non-queer company. This depended on which culture I was residing in, East or West, urban or rural, etc. Because I believe being queer, or of colour, is for someone else to deal with, not me. I am already queer and of colour inside, so why do I need to express it on the outside? For whose pleasure, for whose benefit?

In hindsight, I feel the whole exercise of self-awareness was ultimately futile. I still wasn’t expressing myself; I was only defining myself. The definition of who I was sexually or racially never led to my curiosities as an artist. The cultural shift from East to West, then back to East again, made it even worse as I had to deal with cultural dissonance for a second time. This constant adaptation and assimilation between sexuality, race, and culture made me second guess my creative directions. Should I have considered my queerness, my colourfulness, or my heritage when creating a work? On the other hand, I do feel that it is important to understand where I belong in the social architecture of humanity because that is the way others see you and it’s a good foothold on how to answer their questions. But it is only a building, a physical structure of walls … and you can escape this building in order to construct an unquestioning landscape outside.

Recently, I attended an arts talk in my hometown of Kota Kinabalu, in the Borneo state of Malaysia. It is a small town whose economy is rooted in palm oil, timber and tourism. It is also one of the most biodiverse places on the planet, comparable only to the Amazon. Needless to say, we get a lot of foreign researchers and political saviours coming to the island. There was a talk organized by a local arts studio which featured a Southeast Asian curator of a regional museum. In an effort to persuade the curator that they should collect more Borneon art, one American audience member accusingly asked the question which I paraphrase, “Why aren’t you showing or buying more art that speaks to the concerns of people locally … to their voices and concerns?” The sentiment was kind enough. The problem, for me, is why he had to speak for others? For the “locals”? A friend of mine, who also attended the talk with me, berated me and called me a coward for not speaking up at that point. I also agreed with my friend. I should have; but the moment was subtle. And, the moment was subtle to me because these kinds of moments have been normalized for us to hear. I heard it, but I also didn’t want to offend. The norm in most Southeast Asian cultures is not to point fault at someone. It is also a norm not to embarrass a foreign guest. But we didn’t need to be defended by an outsider. How does someone who is not part of the community know what the community needs and what their voices are? So, I felt that if I had been younger and heard this comment, I may have thought to myself that my creative production needs to be in relation to my community, to my culture. How does my expression fit into my culture? I find these questions of self-doubt for an artist to be damaging. The weight of my heritage and my sexuality does not fall on my expression. I am not obligated to be racially or queerly authentic. The works I’ve created, past and present, have always kept these personal elements of race and sexuality at arms length. Again, it is innate. But its quietness doesn’t mean that it is entirely silent.

SMB: Thanks for sharing this recent experience in Sabah. And now, I wonder: did you experience this in Canada? This inclination to conform, to accept what “is”? Was the pressure to deal with your gender, sexuality, and culture happening then? Is it still present?

CCCF: My time in Canada didn’t have the same kind of pressure because there was no way that someone like me was going to make anything substantial or be a representative of any group. So no, there was no pressure for me because I was ignorant of what the media arts could do. At the time, I didn’t see an Asian person standing on stage presenting their work, or having a solo show in a gallery. I didn’t see it, so it wasn’t important. I didn’t aspire to it. I also didn’t aspire to be white, or be with the white groups in the arts scene. This includes the white queer groups as well. They were a different species. For me, it felt unnatural to co-mingle. This kind of prejudice came from my own insecurities perhaps, but it felt natural as well. At the time, token friends of colour were also prevalent. Perhaps subconsciously, I didn’t want to be part of that. But easier said than done. That was a long time ago of course. Nowadays, I doubt it’s the same. What if I had never met Nicole?

SMB: Where are you heading? Where is Chris Chong Chan Fui five or ten years from now? What does the artistic landscape look like? You have a lot of ideas and opinions about where things could go, so where might they go? What would you tell a 19-year-old queer racialized art student?

CCCF: I think I finally understand that, for me, it’s a life-long process that doesn’t come with any goal or ending. It’s something unstoppable and fluid, with its source based on what personal experiences I’ve come across, past or present, and what statement I want to make. Why was I interested in the birds’ nest industry or artificial flower manufacturing? It isn’t because of its environmental, societal, or flora/fauna impact. It’s because it was common and it surrounded us. There is a relationship between this very specific industry to the way I see the world. The industry exemplifies something specific, and my instinct tells me it’s saying more. So there is no goal, just a movement in a different direction. I believe I will continue to work in the same manner, using many different materials, mediums, and spaces. It’s endless and massive.

The artistic landscape is rather disappointing. From what I see in the visual arts in East Asia and its relationship to the stakeholders in Europe and the Americas, it is no different than working in the fashion industry. The manner of basic human respect is lacking. It’s a lot of falsehoods, protectionisms, and self-serving ambition under the guise of artistic/ cultural support, which is further compounded by the all-too-kind Asian mannerisms which deceive most foreigners. But this doesn’t involve me. I say that because the art industry, like the fashion or car industry, will continue with or without me. I will be invited in or discarded, no matter what I say or do. I have no control over it. It is irrelevant in my life.

As I said above, I have no choice in the matter. My experiences and my statements, in the form of art, will come in whatever form that is available to me. There is no presumption for production, therefore there is no assumption in involvement.

But what I am involved in is in the space around me. I am impacted by what is happening around me and I have no control in whether to engage or not. I am always engaged. To that 19- year-old racialized art student, my advice would be to be conscious of your surroundings. Fantasize about it. Take control of it by messing it up. Never take what we see and experience at face value. Leave that for the journalists and the documentarians. Just because you look provocative to others, or have a provocative cultural story, doesn’t mean that this is your form of expression. You don’t have to highlight your differences. Highlight the world you see around you. All too often we are told that our individuality is our strongest force. Yes, I believe that this is true. I believe we need to hold true to that inside. But as racialized artists, we are not obliged to prove our difference, our uniqueness. Art is not supposed to validate our existence. Art does not validate our existence. An artwork about your heritage does not validate you as a person of colour. An artwork about your queer identity does not validate you as queer. So let’s not use our racial or queer identity as a rallying cry in the arts. Seeing art that so blatantly expounds on the power or specialness of being queer or Asian seems cheap to me. It’s a singular, clear public statement on our individuality. I think we’re more complicated and open-ended then that. Our existence is relative to what happens outside of us, in the spaces around us. We can then internalize it. Our feeling of this outside- and-inside feeling is filled with risk and uncertainty. I believe this dissonance creates personal expression, an involvement between the outside and inside world. It’s entirely grey without any solid footing; filled with risk. The 19-year-old needs to know that this grey risky space is actually a safe place.