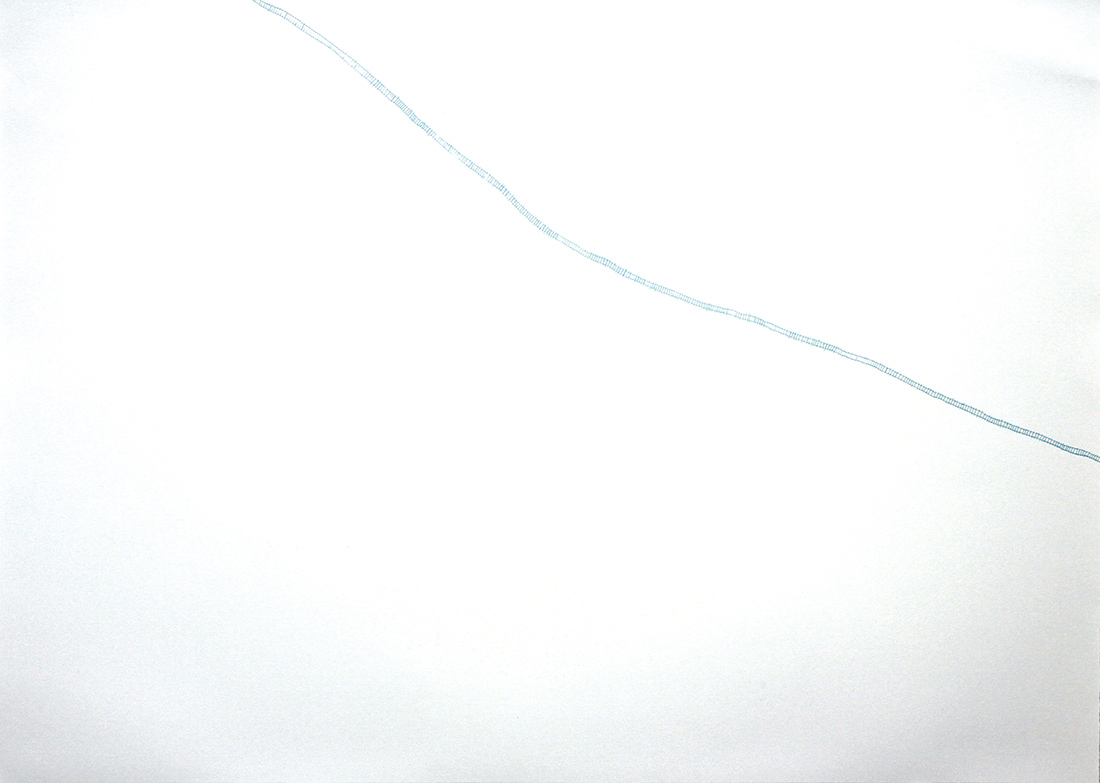

Lisa Myers, Blueprints: Garden River (2015). Series of serigraphs on paper using blueberry pigment, each 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Maya Wilson-Sanchez

ON MAPPING, STORYTELLING, AND COOKING

A DISCUSSION OF LISA MYERS’S BERRY WORKS

INTRODUCTION

Meeting Lisa Myers in 2014 was deeply influential to my learning and understanding of Indigenous survival and resistance. At the time, I was a student at OCAD University and taking a sculpture course that Myers was teaching on narrative strategies. It was during this time that I learned something from Myers that completely changed my perspective regarding contemporary cultural production by Indigenous artists. I learned about tradition, and not the European idea of tradition where tradition is something static that is kept as unchanging as possible in order to maintain its integrity. The idea of tradition that I learned, which comes from Indigenous writers and curators including Myers, as well as Candice Hopkins, Deborah Doxtator, and Wanda Nanibush, is one that recognizes tradition as a dynamic practice that changes and adapts to fit the needs of its current communities. This shift in understanding made me realize that the continuation of the cultures and knowledge of Indigenous peoples can take on many forms and processes. I still find this idea revolutionary, and it has been crucial to my research on contemporary artistic production by Indigenous artists across the Americas these past years. Understanding tradition through this perspective has allowed me to see contemporary art as a clear continuation of traditions practiced hundreds and thousands of years ago on this continent. Myers takes part in this practice, as her work archives family history and continues a tradition of Anishinaabe storytelling.

This essay discusses a number of artworks by Myers that use berries as a medium and a method. It describes how these works do the important work of sustenance, survivance,1 and remembrance in two ways. First, by recognizing the continuous intervention of the past and acknowledging the existence of geographical ancestry and intergenerational memory as having a real presence within the experience of time and space, and second, by using cooking and eating as a method for collective learning, healing, and remembering. Her work will be analyzed as an intimate way of relating to land that demonstrates how personal history and cultural memory can be transmitted using new methods.

What I call the Berry Works is a loose collection of artworks that in one way or another include berries. This series comprises of screen-prints, animations, installations, videos, and performances which Myers began in 2006 and is still producing. The first and second sections of this text discuss a series of maps printed with blueberry pigment. Maps are an abstraction of land and space in order to visualize specific information. Myers’s blueberry maps visualize land using the products of the land, concluding in a complex and layered mapping practice that is indicative of multiple histories and intergenerational experience. The third and fourth sections examine Myers’s videos and participatory performances in the context of the history of agricultural labour in Ontario. I also examine the role of cooking within Myers’s practice, and argue that through her artwork, she provides sustenance and sustains community. The last section analyzes some of the Berry Works as an archive of Indigenous time and history while also briefly discussing other projects that shift perceptions of how archives are defined and maintained.

Storytelling and keeping histories alive by using a variety of media is one of the main themes explored in this research. In an effort to use storytelling methodologically, two conversations with Lisa Myers about herself, her family, and this series of work are included in this essay. This highlights how an artist’s own history and stories can be acknowledged as valid sources commensurate with cited academic texts. Discursive practices that support and encourage relationship-building are found at the core of many Berry Works, especially in the participatory performances. Therefore, it is fitting to use my conversations with Myers not only as a framing device to understand the themes and ideas in her work, but also as a method of using discursive research practices in a scholarly context where sharing stories becomes just as pertinent to the development of the text as other forms of academic research. Lastly, some sections begin with quotes from Myers’s Artist Talk at Onsite Gallery in 2017. During this talk, Myers purposely started her presentation three times. Each time she began, she introduced a different history and perspective from which to understand her work. Doing this was an exercise in thinking about how artists present, brand, and design themselves in both art contexts and beyond. It was a playful and meaningful way of critically thinking about how Indigenous artists identify themselves and how their artwork is presented through Indigenous identity. These epigraphs frame my discussion and introduce important information and major themes found within the Berry Works.

TRAIN TRACKS, MAPS, AND PSYCHOGEOGRAPHY

There are so many ways to begin. So I will start by saying that my name is Lisa Myers. I grew up on a farm in Milton. My mother was born in Shawanaga First Nation. If she were alive today, she’d be a band member at Christian Island, otherwise known as Beausoleil First Nations, otherwise known as Chimnissing. My dad’s family settled in Oakville, and he is Austrian and English. That’s one way to start.

—Lisa Myers, Artist Talk at Onsite Gallery

In August 2009, Lisa Myers and two of her cousins walked roughly 250 kilometers over eleven days. This walk closely resembled the walk that Myers’s maternal grandfather, Vance Essaunce, had undertaken in 1919 as a young boy. Myers’s grandfather was running away from Sault Ste. Marie—where he was being forced to live at the Shingwauk Residential School—to the town of Espanola. Myers’s exploration of her grandfather’s journey and the artwork she created inspired by this experience uses family history to address contemporary issues.

Myers is an independent curator, artist, and educator currently based in Toronto and Port Severn. She has Anishinaabe ancestry and grew up in southern Ontario. For over a decade, Myers has experimented with different ways of using berries as a material and method for the creation of art. Sometimes the berries are used are as a material nexus in Myers’s participatory performances that include the sharing and eating of berries. Sometimes, blueberries are eaten using wooden spoons that become stained with the anthocyanin pigment that give blueberries their colour, which Myers later uses to create animations. In other cases, Myers experiments with various processes such as cooking the berries, straining them, or drying them to create a pigment to be used as a kind of paint or ink that can be used alone, mixed with clear screen printing ink or other binding materials.

Lisa Myers, Blueprints: Garden River (2015). Series of serigraphs on paper using blueberry pigment, each 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Myers’s Blueprints are a series of prints that use blueberry pigment as the ink. Blueprints: Garden River (2015) and Blueprints (2012) both consist of four screen-prints that show where Vance Essaunce crossed railroad bridges during his journey. In presenting her grandfather’s journey and the train tracks he followed while surviving on the nearby wild blueberries, Myers’s Blueprints explore how we locate ourselves and how we create a sense of belonging through our land, our food, and our stories. Blueprints illustrates where the Mississagi River meets Lake Huron, the first point in Essaunce’s journey where he heard Anishinaabemowin being spoken. While on the bridge, Essaunce spotted a group of Anishinaabeg cooking who invited him to join them. This would have been his first meal since leaving the residential school, and the first time he could have freely spoken in Anishinaabemowin, since speaking in Indigenous languages was forbidden at residential schools.2 Blueprints: Garden River depicts the crossing of another railroad bridge in Garden River First Nation, which is now well-known for having large graffiti across it that reads “THIS IS INDIAN LAND.”

In both sets of prints, the first three screen-prints display water, land, and train tracks as discrete maps, while the fourth print joins all these aspects together. Myers explained that this dismemberment of the landscape references Geographic Information Systems (GIS).3 GIS captures, stores, analyzes, and presents information about land. Most GIS maps can be programmed to contain different kinds of information and the software displays this information in layers. GIS is widely used by governments and corporations to analyze land for development or resource extraction. Used in this way, GIS technology is a tool that furthers capitalist and colonial agendas.4

In “Mapping Indigenous Lands,” Mac Chapin, Zachary Lamb, and Bill Threlkeld state that “those in power have employed maps over the centuries to mark off and control territories inhabited by indigenous peoples.”5 Myers’s appropriation of the language of GIS mapping becomes a form of mimicry or reproduction subverting what it mimics. She states her Blueprints series critiques “the hegemony of geographical information, and the determination of power and wealth through that information.”6 She believes that her work “doesn’t hold that kind of information, but it holds different layers of the narrative and the elements that [her] grandfather survived on. It’s the layers of survival rather than the layers of power and value.”7

One of the most intriguing qualities of the Blueprints series is how it depicts a personal way of relating to space. In mimicking GIS, the artworks show how this technology, and mapping in general, can be used to present a more nuanced way of experiencing land. James Corner claims that “mapping is never neutral, passive or without consequence” but perhaps “the most formative and creative act of any design process, first disclosing and then staging the conditions for the emergence of new realities.”8 Under the guise of scientific objectivity and positivist ideology, modern European cartography conceals the things that it is creating and silencing at the same time. The plainness of European mapping practices that follow the colonial encounter is a rhetorical device for the ideology that all space can be known rationally and empirically through the use of the Cartesian grid and the Mercator projection.9 As terra nullius, the Americas were cartographically invented through imperialist ideology as a blank space that is empty and available for the taking. This is why the word place, as used in critical cartography to describe space shaped by experience, is so valuable to this discussion. Margaret Pearce writes:

Western cartography is characterized by specific assumptions and structures, and those structures carry limitations. The Western map is an assemblage of ideas about representation and reality emphasizing an “all seeing” perspective, a fixed scale, and mathematical projection from sphere to developable surface …. Through statistical and graphic generalization, the features of the map are categorized into the hierarchies of quantitative and qualitative data …. The visual aesthetic that results from those accumulated layers of homogenizing categories communicates a geography of modernity, universality, detachment, and placelessness. In other words, it is a visual language more commonly used not to portray place, but to erase it.10

Lisa Myers, Blueprints: Garden River (2015). Series of serigraphs on paper using blueberry pigment, each 55.9 x 76.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Although Lisa Myers adopts the formal language of mapping, her use of walking as a method of research, and her choice of materials foregrounds the critical and psychogeographical idea of place. By embodying the experience portrayed in her maps, she uses mapping as a tool for storytelling.

The critical use of maps and mapping in art became established in the 1950s and 1960s within the Situationist International (SI), a political group based in Paris with roots in avant- garde art. The development of psychogeography became central to SI. In the first volume of SI’s journal, Internationale Situationniste, psychogeography is described as “the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviors of individuals.”11 There are obvious and important similarities between Lisa Myers’s Blueprints and the methods of psychogeography, most notably the emotional, historical, and psychological relationship between humans and space.

Myers’s work utilises two methodologies of psychogeography: détournement and dérive. détournement is described as a sort of plagiarism or hijacking of something “into a superior construction of a milieu.”12 Her mimicking of GIS is a type of détournement because she subversively copies an existing structure in order to criticize it. Merlin Coverley writes, “plagiarism is one of the methods by which détournement seeks to liberate a word, statement, image or event from its intended usage and to subvert its meaning.”13 By reproducing the pre- existing aesthetic elements of mapping, Myers liberates this medium to be able to depict place.

dérive is “a technique of transient passage”—a sort of drifting through an environment.14 Although sometimes described as an aimless or unconscious drift akin to surrealist wanderings, Coverley clarifies that the dérive “is not without purpose. On the contrary, the dériveur is conducting a psychogeographical investigation … the dérive takes the wanderer out of the realm of the disinterested spectator … and places him in a subversive position as a revolutionary.”15 Myers’s eleven-day walk can be understood as an investigative dérive into her grandfather’s journey. Although she could have easily driven alongside or near her grandfather’s route, the pace of walking was important to her experience.16 She states that by walking, she was “able to bring the places in the story [she’d] heard to life.”17 Unlike an aimless drift, Myers’s walk became an exploration of a route outlined by her grandfather’s story—an exploration that allowed Myers to place herself within the story and within the geographical reality of the story’s location.

STORYTELLING, REPETITION, AND REMEMBERING

In many Indigenous traditions, storytelling is much more complex than simply the repetition of stories from one person to another. Cutcha Risling Baldy claims that “stories were and are how Indigenous peoples define and redefine their sovereignty, spaces, cultures and knowledge.”18 Myers explains that one of the reasons her series is titled Blueprints is because “the stories that we hear from our family help make up who we are. The stories are blueprints. They help me locate myself … there’s a narrative there and that narrative influences who I am and how I think about myself.”19 Furthermore, Deborah Doxtator, commenting on the work of Christopher Jocks, writes that “tradition is really kept alive more by a community of people dynamically using, enacting and changing knowledge, and it is these processes, and not how much static content is actually preserved, which is important.”20 Thus, the very nature of storytelling undermines the Western notion of an ahistorical Indigenous “static” tradition and acts as a framework towards decolonization.

Candice Hopkins writes that in art, “since the dawn of mechanical reproduction, the copy is understood as subversive: its very presence challenges the authority of the original.”21 She continues by explaining that “replication in storytelling, by contrast, is positive and necessary. It is through change that stories, and in turn, traditions are kept alive and remain relevant. In the practice of storytelling there is no desire for originality, as stories that are told and retold over time are individual but communal.”22 Like many contemporary Indigenous artists such as Skawennati, Christie Belcourt, and Bonnie Devine, Lisa Myers uses storytelling to ensure the continuation of contemporary Indigenous history and culture.

When Myers was in her late twenties her grandfather told her about his journey and years later it inspired her walk and the work that came from it. Myers states, “it was important that I took that walk because then it didn’t only stay as my grandfather’s story, but I started making my own story of that route … and that seemed important instead of always repeating his story … it was a way of finding myself in that story.”23 By repeating his experience of the journey, she developed new relationships to the story and that land, and now shares both of these experiences through artworks. The Blueprints are a form of storytelling that reproduces her grandfather’s journey as a way for Myers, and by extension, her audience, to learn about resistance and highlight an experience that, unfortunately, resonates with many. By adding to the story and presenting it in new ways, Myers is dynamically using familial knowledge, memory, and history to speak to a contemporary moment when Canadians are hoping to have serious conversations about colonization and reconciliation.

Her artwork is complex and depicts an embodied, personal, and intimate experience of space using mapping, psychogeography, and storytelling. Blueprints uses two kinds of reproduction—the first is a subversive act of mimicking GIS mapping, and the second is the repetitive act of continuation and sharing that is inherent within storytelling. It appropriates the well-established language of cartography for new ways of sharing family history with the intent of resistance, as it creates room for the perseverance of the strength and courage found within the transmission of her grandfather’s story to a larger narrative.

STRAINING, ABSORBING, AND PICKING BERRIES

I’m just going to start over. This work came from the kitchen and from my time in kitchens. These kitchens were domestic, some were professional, some were around a fire.

—Lisa Myers, Artist Talk at Onsite Gallery

After making the blueberry ink maps, Myers created a video and another set of prints, Straining and Absorbing (2015), that used blueberry pigment. Building upon the Berry Works that begin with her grandfather’s story, and then included her own experience of that journey, Myers began to think about Straining and Absorbing blueberries as a metaphor. The necessary processes required to make blueberries into a liquid involves separating, refining, and isolating certain parts of the fruit to only those that are useful. Myers explains, “I cook and from those berries I am able to make the colour I need. The colour fades after a time, but after boiling and straining, the consistency is smooth, uncomplicated and desirable.”24 The metaphor of Straining and Absorbing asks what parts of history have been discarded? Which stories have been deemed not useful? Whose bodies and beliefs have gone through a process of separation, isolation, and refinement? This process calls to mind what is left behind when everything that is not deemed valuable to a certain process is thrown away.

The video of Myers creating the Straining and Absorbing prints was exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario alongside the prints in 2015. The twelve-minute video shows Myers pouring the cooked blueberry purée into a strainer and onto a screen printing press, and then pressing the pigment through the screen. The blueberry pigment then becomes absorbed by the paper underneath, eventually creating an abstract, purple shape. Myers describes Straining and Absorbing in relation to “ideas of assimilation and colonization where you’re straining to survive. What do you leave behind and what do you compromise to belong or fit in … what do you have to leave behind of yourself?”25 In understanding straining through the French culinary tradition “as a technique that is used to redefine the ingredient by removing fibre, skins, and seeds, thereby creating uniformity and consistency,” Myers states that “straining to survive, or even to be accepted means the less digestible parts of stories need to be retained, traced, remembered, and told.”26

Lisa Myers, Straining and Absorbing (2015). Stills from digital video using blueberry puree, screen, strainer and paper. Courtesy of the artist.

Picking berries—whether it was her grandfather picking blueberries to survive a long journey, or picking strawberries as wage labour—is part of Myers’s family history as well as the history of Ontario. Myers’s family moved from the Shawanaga area in Georgian Bay to Clarkson to pick fruit for wage labour. In speaking about her artwork, Myers states, “I began with the basics. An action of picking and gathering, an act that I imagine my mother and her mother each bent down to these small plants and berries as people who moved south to farms to pick strawberries.”27 Myers’s Berry Works bring attention to how food involves a relationship to land—a relationship that is entangled with family stories and the socioeconomic history of twentieth century Ontario.

For many years, Myers has cooked, shared, and served food as key components of her performance-based artwork. She views the production and presentation of food as significant and describes food as having the “capacity to connect people with places, history, and a sense of cultural identity.”28 She believes that “food symbolizes visceral connections to the past, and stands in as a cultural affirmation that people need to reclaim as their own.”29 By using cooked and strained blueberry pigment as the ink for her screenprints, Myers makes a direct connection to her grandfather’s journey and asks her viewers to think of Straining and Absorbing as methods of survival. These works present food as something directly tied to land and emphasize the meaning that food carries for recalling memory and reclaiming history.

The vegetable and fruit industry in Ontario has a history of providing low wage and precarious jobs for seasonal and migrant workers that often involve questionable or problematic working conditions.30 Research into this history shows that fruit pickers were discriminated against on the basis of gender and race, which made that kind of work especially susceptible to Indigenous women in Ontario.31 When I asked Myers if she incorporated memories of her grandmother and mother who picked fruit into in her work, she mentioned how their labour was more about how “under circumstances of low income, they were still able to create a home and feed their families.”32 Myers’s familial history of picking berries straddles the history of agricultural labour within a capitalist economy and the idea and act of gathering local food for sustenance. She states, “I was thinking about the food that comes from the place my family is from. When you’re connected to a place, you know the food that grows there.”33 This conception of picking berries is one that undermines the exploitative labour conditions of food harvesting that continues to this day, and instead tries to understand the gathering and consuming of food as an act that ties us directly to land and community. In Myers’s work, food is about survivance and ceremony.

In the summer of 2014, Lisa Myers staged Shore Lunch, a three-part, participatory performance at the Toronto harbour on the shores of Lake Ontario. Exploring the history of Toronto’s waterfront, Shore Lunch included a mobile kitchen used to prepare and share food, as well as videos and performances. This work was a dedication to Myers’s mother, who was talented at fishing and would “go fishing and pull up on the shore and fry up the fish and have a shore lunch.”34 The first performance, titled Shore Lunch: Leaving Marks involved Myers using carved rolling pins to create print-block, take-away, postcards that were printed using berry pigment, while also serving the audience strawberry drinks. Presented a month later, Shore Lunch: Landing Under Water was a screening of two video works, one of them the 2013 animation from then on we lived on blueberries for about a week which depicts animated blueberries on a birch spoon that creates a travelling horizon line set with a soundscape of water and trains. A makeshift seating area, created from upside down buckets, allowed the audience to sit and watch while they were served berry drinks and fry bread. The last performance, Shore Lunch: Listen To This, was a collaboration with Melody McKiver who played the viola, while Myers played guitar. Both artists performed songs they had written for the berries, for water, for fish frying, and for wild rice.

Myers’s artistic labour and practice is deeply informed and connected to the experiences of working in kitchens and learning about food. In the years that I have known Myers, I have sensed an ambivalence from her regarding certain aspects of her artistic work. After hearing her share at an artist talk that she is uncertain about cooking for people in her artwork, I asked her if she thinks about the meaning of cooking as part of her artistic practice in relation to the history and understanding of cooking as devalued women’s labour. She answered, “I was less self-conscious in the beginning, but more self-conscious recently about being a woman with an apron on making stuff for people.”35 Myers explained that being a restaurant chef and a cook at the Enaahtig Healing Lodge and Learning Centre between 1997 and 2009 greatly shaped her role as a cook within her artistic practice. She said, “When I think about my work at Enaahtig, it was a strong position to be in—not only strong as in powerful, but as an important responsibility.”36

Cooking within Myers’s art practice involves much more than the optics of a woman cooking and all the associations that comes with such a sight. It is about sustenance and relationship, just as Myers experienced when she worked at the Enaahtig Healing Lodge. At the time, Enaahtig was a multi-nation Indigenous centre that supported social services, healing, and community events using culturally appropriate Indigenous knowledge and practices. At Enaahtig, Myers tells me:

Sharing food was really important. It was part of ceremony where feasting is really important. In a ceremonial sense, food, and berries in particular, function to feed more than your physical body. There are these beliefs that it feeds a certain spirit that you need to help you get through certain things. I don’t consider my work ceremonial, but I think that the material—the material being the berries or the food items—references a function that goes beyond physical sustenance. Maybe an emotional sustenance—I don’t think they’re separate …. It was a different context than a restaurant. I was part of the whole team that worked there. It was a different way of thinking of the cook or the chef as part of a larger team that was supporting the community.37

Lisa Myers, Shore Lunch – Leaving Marks (2014). Performance, Harbourfront Centre, Toronto, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Lisa Myers, from then on we lived on blueberries for about a week (2013). Still from digital video using blueberries and birch wood spoons. Courtesy of the artist.

How Myers envisions herself can be traced to the role and responsibilities that she had at Enaahtig. The role that she has created for herself as an educator, artist, curator, and writer is also rooted in collaboration, community engagement, and emotional and physical sustenance.

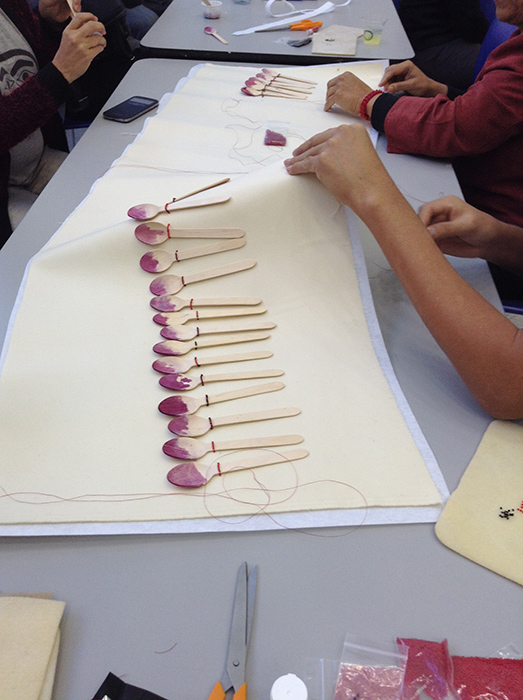

The gesture of supporting or sustaining a community by being responsible for providing food comes up in more direct ways during a participatory performance Myers created for an event in January 2016 organized by Mohawk curator Ryan Rice called WELL READ: Activating the TRC’s Call to Action. This event was a four-hour collective public reading of the ninety-four Calls to Action proposed by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Individuals could read any of the recommendations aloud using a microphone in the lobby of OCAD University. Myers provided blueberries to the individuals who were gathered to listen and to participate. The berries were shared using small paper cups and birchwood spoons. After consuming the berries, participating individuals were invited to take their berry-stained spoon and bead it into a line of spoons previously used by other participants, thus creating a collective document of this community event. Myers tells me: “those Calls for Action bring up a lot …. I felt like that was the best thing I could do in that moment …. [We created a] collective document to mark this moment where we came together and listened and we shared. And we shared berries so that we could listen. The berries were there to help us listen.”38

Lisa Myers, WELL READ: Activating the TRC’s Call to Action (2016). Participatory Performance, OCAD University. Courtesy of the artist.

Many of the Berry Works involve collective care administered by Myers. These works are about relationship and an exchange among people, where discursive practices shift the focus of the artwork from the artist and the art object, to the information or emotions being shared and the relationships being created or sustained. These kinds of practices are directly tied to how Myers envisions cooking. She states that much of her work comes from the perspective of “owning the space of the cook as feeding the movement, or being essential to a social change or healing.”39 She adds, “there is a word in Ojibwe for cook that kind of translates to something like feeding your ancestors or feeding a spirit. That’s the name of what a cook is, and in that name you see the significance to that role in this context.”40 Her work presents the action of cooking as a powerful artistic gesture within a context where cooking is usually coded as devalued women’s labour. She uses cooking as a method and activity in order to shift the understanding of the labour of cooking to one that sustains community and fosters relationship. In this sense, cooking as artistic labour involves a feminist and decolonial gesture and perspective that presents food in the context of land, history, memory, community, and sustenance.

HISTORY, MEMORY, AND CREATING ARCHIVES OR THERE ARE SO MANY WAYS TO END

I’m going to start over. Nisaawaygamii kwe ndizhnikaaz. I just said: hi my name is center of the water and woman. I’m from Chimnissing Big Island.

—Lisa Myers, Artist Talk at Onsite Gallery

While participating in an artist residency at the Banff Centre, Lisa Myers met artist Maria Thereza Alves, whose projects also focus on memory and include the themes of borders, plants, survival, land, and history. Alves saw some of Myers’s Blueprints at Banff, and asked upon seeing the work “at what point do personal stories become part of dominant history?”41 Myers describes this question as being an important turning point in the development of the Berry Works because it placed her work in the context of Canadian history.42 This last section examines the Berry Works in the context of creating history, storytelling, and incorporating intergenerational memory into artworks and archives.

Recent developments in a number of cultural institutions have shown an interest in collective memory, familial memory, personal archives, and oral histories. A current example includes Myseum, an organization without a dedicated physical space that focuses on pop- up events, collaborations, and programming that highlight varied aspects of Toronto’s history. Past projects include a self-guided audio tour of Kensington Market and its history, multiple collaborations with the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives to commission new video art and exhibit the stories of the Latinx LGBTQ community in Toronto, and a collaboration with the Department of Public Memory, a two-person artist collective that shares archives with the public that contain overlooked stories and histories. Another example is the Musée de la Mémoire Vivante, or Museum of Living Memory, located in Saint-Jean-Port-Joli northwest of Quebec City. This museum collects mostly Québécois oral histories using audio and video recording. It also includes educational programs to share oral histories in public schools, as well as outreach strategies where museum staff travel to different sites to collect stories in order to diversify the kinds of histories presented in their archive. My last example is the Family Camera Network, a multi-year project that includes six education and cultural institutions and over twenty-five scholars, who research the relationship between family and photography. This large project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, includes conferences, publications, exhibitions, and workshops, as well as the collection of thousands of photographs from Canadian families and video interviews about the stories pictured in the photographs, which are archived at the Royal Ontario Museum and the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

These new practices that are heavily based on public participation, have shifted the understanding of archives to include a more fluid definition of what constitutes an archival object, and the qualities that deem an object or history worthy of archival preservation. In the case of the Family Camera Network and the Museum of Living Memory, these public collections can help explore the diverse stories of everyday Canadians in a way that allows the (re)creation of Canadian history that decenters dominant narratives. The collaborative, collective, and participatory programming of Myseum also redefines the understanding and use of archives in a way that invites the public to share and create their own histories of Toronto. These kinds of discursive and collective practices that involve the creation of histories through stories are central in Myers’s artistic practice.

Some of the Berry Works function along this archival tendency, creating new spaces and expressions for histories. There is a great power in artists creating their own archives and being able to present their own stories. Through the Berry Works, Myers creates work about her family, the history of residential schools, and the history of food and agricultural labour in Ontario. In Blueprints specifically, she creates an archive of not only her grandfather’s story, but also her own psychogeographic encounter with that space. The Blueprints archive this land through its very/berry materiality, physically linking the map to food and sustenance found on the land that is being depicted. GIS technology creates a map and archive of certain kinds of information and knowledge useful for capitalist development. In contrast, Myers creates an archive of the entangled narratives, emotions, sensations, conversations, and actions present within this geography.

In recognizing the continuous intervention of the past, Myers’s Berry Works acknowledge the existence of geographical ancestry and intergenerational memory as having a real presence within the experience of time and space. Within an Indigenous context, in the words of Jackson 2bears, it is possible to “think about history and ancestry as not something that we ‘inherit’ from the past, but rather as something animate (living) that co-exists with our experience of the present.”43 Thinking about the geography of ancestry, “as opposed to a chronological or genealogical concept of history and ancestry,” is useful in understanding some Indigenous conceptions of time.44 The Berry Works portray a geography of ancestry while presenting a history where land is a vital part of understanding familial stories.

Myers’s artistic production—and more specifically her actions of gathering stories and then sharing them in new ways—allows us to imagine archives and histories as detached from institutions. Her work uses storytelling as a way to gather and share information in ways that are critical of colonial collection practices, and in a way that asks: what stories do we tell ourselves? Whose stories are welcome and which ones are discarded? Which stories make up who we are? Although the Berry Works now have multiple functions and meanings, their origin is tied to a story of hardship and fugitive escape from cultural assimilation and abuse. Regarding the inclusion of this kind of storytelling and history in her works, Myers states:

We share traumatic histories. There is an importance, but there’s also a burden … I think I’ll always think about it as a gift, but I don’t want to tell the story over and over again anymore. The story shouldn’t be silenced, but it should be instrumentalized …. It could be used in its reference to a lot of what is being discussed about reconciliation and residential schools.45

In this way, she is less interested in continuously sharing the story, and more interested in having that labour shift to other ways of presenting the work. Some of the Blueprints are now in public collections such as the Walter Phillips Gallery and the Indigenous Art Centre. Her grandfather’s story is available online and also through publications where it can be used as an educational tool to teach Canadian history through Myers’s art and her family’s stories.

Olivia Gagnon writes about how feelings of entanglement engage with the past. She describes feeling entangled as “one’s complex situated-ness in the tangle of history” and adds that “to perform one’s feelings of entanglement is therefore both to refuse to detach from one’s pasts—to know that one could never be detached from them—and to refuse to be relegated to that past.”46 Myers’s Berry Works incorporate feelings of entanglement in their depiction of family stories that are intertwined with the history of this land, and also in the way Myers refuses to forget this history by incorporating its memories into the present through the use of mapping, animation, and participatory performances. The Berry Works present the history of Ontario in stories, memories, and experiences of place where the use of specific materials and discursive practices are a way of marking and making history. The histories of colonization, agricultural labour, Indigenous ceremony, sustenance, railway development, and much more are entangled in Myers’s Berry Works, as she refuses to present a history that is anything less than these complex experiences coming together.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Deanna Bowen for inviting me to take part in this publication, as well as the staff at the Media Arts Network of Ontario for all of their help and support. I would especially like to thank the participants of the 2016 Decolonizing Conference for their insights, as well as Gabrielle Moser, Anna Cox, and Julian Jason Haladyn who read and contributed feedback during different stages of this essay. This research would not have been possible without the generosity of Lisa Myers, thank you for the wonderful and rich conversations.

NOTES

- “Survivance” is to a term coined by Gerald Vizenor that refers to an active survival and presence of Indigenous peoples. Please see Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance for further information on this term.

- Lisa Myers, interview with Maya Wilson-Sanchez, March 21, 2016, Toronto, Ontario.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2016.

- Not all GIS mapping is used this way. In fact, there has been significant research into how Indigenous peoples appropriate GIS technology to map their own lands. This approach is sometimes called PGIS (Participatory GIS). For examples see “Mapping Indigenous Lands” by Mac Chapin, Zachary Lamb and Bill Threlkeld or “Participatory GIS – a People’s GIS?” by Christine Dunn. A relevant example close to me is some of my father’s involvement in projects during the 1990s and early 2000s that worked alongside Indigenous communities in the northern Ecuadorian Andes. This work included multiple projects to develop better living conditions and sustainable economies in environmentally friendly ways using GIS mapping as a key technology.

- Mac Chapin, Zachary Lamb and Bill Threlkeld, “Mapping Indigenous Lands,” Annual Review of Anthropology 34 (2005): 620, doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120429.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2016.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2016.

- James Corner, “The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention” in Mappings, ed. Denis Cosgrove (London: Reaktion Books, 1999), 216.

- See Mathew H. Edney, “Reconsidering Enlightenment Geography and Map Making: Reconnaissance, Mapping, Archive,” in Geography and Enlightenment, ed. David N. Livingstone and Charles W.J Withers (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999); J. B. Harley, The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, ed. Paul Laxton (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

- Margaret Wickens Pearce, “Framing the Days: Place and Narrative in Cartography,” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 35.1 (2013): 17-8, doi:10.1559/152304008783475661.

- Guy Debord et al., “Definitions,” Internationale Situationniste, trans. Ken Knabb, 1 (1958), https://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/definitions.html.

- Ibid.

- Merlin Coverley, Psychogeography (Harpenden: Oldcastle Books, 2010), 95.

- Guy Debord et al.

- Coverley, 96-7.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Cutcha Risling Baldy, “Coyote is not a metaphor: On decolonizing, (re)claiming and (re)naming Coyote,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 4.1 (2015): 6-7. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/ index.php/des/article/view/22155

- Ibid.

- Deborah Doxtator, “Basket, Bead and Quill, and the Making of ‘Traditional’ Art” in Basket, Bead and Quill, ed. Janet E. Clark (Thunder Bay: Thunder Bay Art Gallery, 1996), 12.

- Candice Hopkins, “Making Things Our Own: The Indigenous Aesthetic in Digital Storytelling” Leonardo 39.4 (2006): 342. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20206265

- Ibid.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2016.

- Lisa Myers, “Artist Talk,” Onsite Gallery, 10 October 2017, Toronto, ON.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2016.

- Lisa Myers, “Rails and Ties, No Visible Horizons, ed. Peta Rake, (Banff, AB: Walter Phillips Gallery, 2016), 38.

- Lisa Myers, “Artist Talk.”

- Lisa Myers, “Serving It Up,” The Senses and Society 7.2 (2012): 174, doi:10.2752/174589312×13276628771523.

- Ibid.

- Canada established the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Programme in 1966 that welcomed migrants from other parts of the world to engage in seasonal and low wage labour in Canada. This practice continues to this day, with tens of thousands of temporary workers a year coming to Canada through this program. Toronto-based artist Farrah-Marie Miranda, who exhibited work alongside Myers in 2017, makes artwork directly about these labour practices. Her 2017 nomadic participatory installation Speaking Fruit includes a fruit stand where local produce can be found. The collaborative project included asking migrant farmworkers “If the fruits you grow and pick could speak from dinner tables, refrigerators and grocery aisles, what would you want them to say?” The workers’ responses surround the installation, exhibiting the harsh reality of contemporary seasonal migrant labour in contemporary southern Ontario.

- In Patrias, C. (2016). “More Menial than Housemaids? Racialized and Gendered Labour in the Fruit and Vegetable Industry of Canada’s Niagara Region, 1880–1945,” Labour / Le Travail 78. Retrieved from http://www.lltjournal.ca/index.php/llt/article/view/5838. Carmela Patrias presents the history of this labour. She shows that the majority of agricultural labourers included migrant or foreign workers that were southern and eastern Europeans, non-British migrants, and Indigenous families from Ontario reserves (69-70). She claims that the discrimination and racialization of these workers led to apathetic attitudes regarding their labour conditions, though it is important to note that “the invisibility of Indigenous seasonal workers had distinct colonial origins” (71). Additionally, in “‘Living the Same as the White People’: Mohawk and Anishinabe Women’s Labour in Southern Ontario, 1920-1940,” Robin Jarvis Brownlie writes that “[f]or First Nations women around Georgian Bay, the local labour market undoubtedly helped promote asymmetrical gender relations” (46). He explains that men “had far more wage-earning opportunities than women in the rural areas around Georgian Bay…Thus, the women had to accept men’s greater role in cash procurement—and the enhanced authority it brought – or migrate to towns in search of jobs” (46).

- Lisa Myers, interview with Maya Wilson-Sanchez, March 21, 2018, Toronto, Ontario.

- Lisa Myers, “Artist Talk.”

- Ibid.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jackson 2Bears, “Mythologies of an [Un]Dead Indian” (PhD diss., University of Victoria, 2012), 4-5, http://hdl.handle.net/1828/3855. This quote from Jackson 2bears borrows heavily from Vine Deloria Jr.’s writings of time and space in God Is Red: A Native View of Religion and Taiaiake Alfred’s Wasáse: Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom.

- Bears, 5.

- Lisa Myers, interview, 2018.

- Olivia Michiko Gagnon, “Feeling Entangled: Affect, Performance, and the Archival Encounter in the Work of Tanya Tagaq and Cheryl Sim,” HemiGSI Fifth Convergence: Unsettling the Americas: Radical Hospitalities and Intimate Geographies, 6 October 2017, York University, Toronto.